With a level of speed breathtaking even for an Egyptian political crisis, the Egyptian military’s role has soured in record time since removing Mohammed Morsi from office last week.![]()

On Monday, the Egyptian army gunned down protestors in favor of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, apparently killing at least 51 people in the process. That came after top Muslim Brotherhood leaders had been detained or arrested in the wake of Morsi’s ouster. It also comes after the new military-backed administration, headed by interim president Adly Mansour, all but announced (then all but retracted) the appointment of Mohamed ElBaradei, the former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, as the country’s new prime minister over the weekend.

Both the short-lived ElBaradei appointment and Monday’s brutality have now alienated one of the most surprisingly odd bedfellows out of the coalition that initially supported army chief Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi in pushing Morsi from office — the Salafi movement’s Al-Nour Party (حزب النور, Arabic for ‘Party of the Light’), an even more conservative group of Islamists that have long competed with the Muslim Brotherhood for influence in Egypt. Like other groups that have come to oppose Morsi over the past year, the Al-Nour Party has criticized Morsi for increasingly centralizing power within the ranks of the Muslim Brotherhood, and their backing for Morsi’s removal last week provided El-Sisi and the Egyptian military crucial support from within Islamist ranks.

But in the wake of Monday’s deaths, the Al-Nour Party announced that it was suspending its participation in the ongoing negotiations over Egypt’s political future. Mansour has now signaled he may appoint Samir Radwan, a technocratic economist and short-lived finance minister in the final days of Hosni Mubarak’s government, as the new interim prime minister, and Mansour yesterday announced an ambitious timetable that would submit the Egyptian constitution to a review committee, submit any revisions to a constitutional referendum within three months, which in turn would be followed in two weeks by the election of a new Egyptian parliament and in three months by the election of a new Egyptian president.

Monday’s bloodshed has increased the pressure on Mansour to bring some semblance of calm to Egypt’s now-chaotic political crisis, with Morsi supporters and followers of the Muslim Brotherhood continuing to demand the restoration of the Morsi administration.

The Al-Nour Party’s leadership is walking a difficult line — on the one hand, it is now well-placed to influence events in post-Morsi Egypt; on the other hand, it’s long been split over how much support to provide Morsi as an Islamist president, some of its supporters opposed Morsi’s removal, and the Muslim Brotherhood will be quick to point out that the Al-Nour Party has turned on its fellow Islamists. By initially supporting last week’s coup but turning on the new transitional government this week, the Salafists may be trying to maneuver the best of both worlds. But after a year where the Al-Nour Party has already splintered, its controversial support for the Egyptian military may shatter it further.

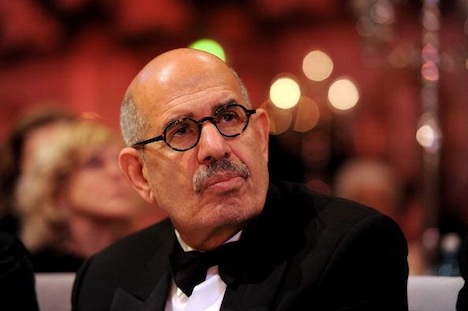

But regardless of whether Mansour can somehow bring the Salafists back into the ongoing political process, and regardless of whether the actual Al-Nour Party can manage to form a united front, their Salafist supporters have now become the key constituency in the latest act of Egypt’s existential drama. After decades of disdain for active politicking, the Salafi movement has shown itself to be a relatively canny political actor in the post-revolution Egypt, and it makes Al-Nour’s leader, Younes Makhioun (pictured above), one of Egypt’s most important politicians.

With the Muslim Brotherhood rejecting Mansour’s timetable and continuing to agitate for Morsi’s return, it’s not clear whether the Brotherhood and the Freedom and Justice Party will even participate in any upcoming elections, even if Mansour manages to avoid delays and carry out three sets of free and fair elections in the next six months. It’s likewise equally unclear whether El-Sisi and the Egyptian military will even let the Muslim Brotherhood contest the elections uninhibited.

Having avoided the taint of being part of Morsi’s ill-fated government and all of its failures — from the November 2012 push to force a new constitution into effect to the ongoing failures of economic policy — the Al-Nour Party stands a strong chance of picking up many of the Muslim Brotherhood’s disillusioned voters as an Islamist alternative.

So who are the Salafists and what would their rise mean for Egypt? Continue reading Why the ultraconservative Salafi movement is now the key constituency in post-Morsi Egypt