At first glance, Turkey’s local elections on Sunday seem like a huge victory for prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (pictured above).![]()

His party, the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party), which has governed Turkey since 2002, had an impressive day, notwithstanding the protests last summer that seemed to weaken Erdoğan’s grip on power, and corruption scandals that led to the resignation of four ministers in Erdoğan’s government late last year.

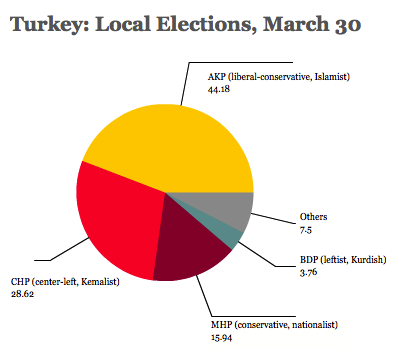

With nearly all of the votes counted, the AKP won 44.18% of the nationwide vote — that’s even more than the 39% it won in the most recent 2009 local elections. Far behind in second place was the center-left, ‘Kemalist’ Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party), with just 26.15%.

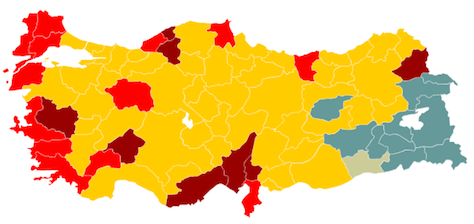

Notably, the conservative, Turkish nationalist Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party) won more support, in percentage terms, that during any election since Erdoğan came to power. The leftist, Kurdish nationalist Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi (BDP, Peace and Democracy Party) won nearly 4% of the vote, picking up several municipalities in the most Kurdish areas in Turkey’s southeast. The map below from Hürriyet that shows the winners throughout the nation:

Though the CHP (light red) is still a strong force in Turkey’s major cities and along its western coast, and although the BDP (blue) thrives in Kurdish-majority areas, the wide swath of yellow demonstrates that Turkey is still AKP country.

Even more impressively, the AKP appears to have won the mayoral contests in both Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city, and Ankara, its capital. Kadir Topbaş, who has served as Istanbul’s mayor since 2004, narrowly won a third term against CHP challenger Mustafa Sarıgül, the longtime mayor of Istabul’s Şişli district, by a margin of 47.85% to 39.93%. Though there are reports of electricity blackouts during the vote-counting and other minor irregularities, Sarıgül has conceded defeat.

In Ankara, however, the race is still too close to call. The AKP’s Melih Gökçek, who has been Ankara’s mayor since 1994, officially won 44.64%, while CHP challenger Mansur Yavaş won 43.92%. Both candidates have declared victory, and Yavaş has alleged ballot fraud. The CHP will appeal the result in what could be a protracted fight over control of the Turkish capital.

But the real fight was never between the AKP and the CHP, and though Erdoğan defiantly claimed victory in a balcony rant Sunday night, threatening vengeance on his enemies, other forces within his coalition will determine whether Erdoğan will be a candidate in Turkey’s first direct presidential election in August, and whether Erdoğan (or another AKP leader) will lead the party into its bid for a fourth consecutive term in government in parliamentary elections that must be held before June 2015.

That’s because Erdoğan’s most serious challengers are the followers of Fethullah Gülen (pictured above in a rare BBC interview earlier this year), a Turkish cleric based in Pennsylvania since his self-exile from Turkey in 1999.

Gülen’s movement, Hizmet (Turkish for ‘service’), has been influential throughout the AKP’s 12-year rule, and Gulenists have been key players in the broad Islamist coalition that Erdoğan built. When Erdoğan rants about the Gulenists that have infiltrated the police, the judiciary and other organs of the Turkish state, he’s not being paranoid — the Gulenists hold a lot of behind-the-scenes power because Erdoğan invited Gülen to help populate the police, judiciary and other offices when he first won power to make it more difficult to push Islamists out of government.

Over the past year, with Erdoğan’s increasing authoritarian streak on display, the Gulenists started to push back, and many Turkish observers believe that Gulenists within the government are behind embarrassing leaks that have exposed corruption within Erdoğan’s government, most notably a widespread bribery scandal involving an Iranian businessman. Muammer Güler, interior minister, Zafer Çağlayan, economy minister and Erdoğan Bayraktar, environment minister all resigned on December 25 of last year, and in a reshuffle on the same day, Erdoğan announced he was also replacing Egemen Bağış, minister for European union.

Ongoing leaks from inside Turkey’s judiciary and government are one of the reasons Erdoğan moved to ban Twitter and YouTube last week in advance of local elections, and his government has been taking steps to purge the government of Gulenists.

No one knows whether the Gulenists — or anyone else — have more damaging information about Erdoğan or other top AKP leaders, but if they do, they’ll be certain to leak it as the August presidential race approaches. In the meanwhile, Syria presents a growing political, security and humanitarian crisis for Erdoğan — one of the few gains for the CHP on Sunday was in Hatay province, which lies on the border with Syria, close to Aleppo.

Though the current leaks don’t seem to have hurt Erdoğan in the local elections, Gulenists were never going to support the CHP, which represents the old 20th century regime that both Erdoğan and Gülen worked together to destroy. Given the lack of a credible alternative (e.g., a split within the AKP or the creation of a new center-left Islamist party), the AKP’s hold on power will be secure.

But it’s harder to predict with confidence that Erdoğan, in a direct presidential runoff against a potential independent challenger, would necessarily win a 50%-plus majority.

Before the corruption trial and the turbulence surrounding the protests in Taksim Square over the demolition of Gezi Park, Erdoğan seemed an easy bet to win the presidency. Turkey’s current president, Abdullah Gül, who was indirectly elected by the Turkish parliament in 2007, was expected to lead the AKP’s next campaign either this year or in 2015. But if Erdoğan becomes too great a risk as the AKP’s presidential candidate in August, his current position might also be in jeopardy. The AKP must revise its internal rules in order to allow Erdoğan to continue his leadership into a fourth consecutive term. Weakened, and with credible replacements like Gül and deputy prime minister Bülent Arınç waiting in the wings, Erdoğan might find himself increasingly sidelined within his own party.

In Turkey, it’s often hard to know when paranoia begins and real threats begin. One of the most mysterious aspects of Turkish government over the past decade has been the Ergenekon trials, a series of judicial actions against many members of the former Kemalist elite. Erdoğan accused many former generals and other secular officials of forming Ergenekon, a secret secular Turkish organization plotting to overthrow his government. No one knows exactly where the truth lies, but there are certainly legal issues surrounding the trials that call into question their fairness.

Though that seems patently absurd, the AKP came to power under Erdoğan a decade ago as a party devoted to ending the era of ‘Kemalist’ politics, during which the military and a secular political elite dominated Turkish government. Routinely, the Turkish military excluded Islamist parties from power throughout the 20th century. Though it initially styled itself as the guarantor of secular democracy, the military grew ever more corrupt through the decades. The line between fact and fiction is especially murky concerning Ergenekon — there probably were a lot of secularists in Turkey hoping for yet another military coup to oust the AKP.

But at this point, Erdoğan’s illiberal rule represents a greater threat to Turkish democracy than the old Kemalist guard. Real or imagined, the Ergenekon example provides a template for how Erdoğan might try to eliminate the Gulenist threat once and for all.

Today, the AKP draws support as an economically liberal, socially conservative, Islamic democratic party. Though there’s no denying that Erdoğan has become less respectful of dissent and liberal political freedoms in recent years, his creeping authoritarianism has always been cloaked in majoritarianism. Erdoğan’s argument all along is that the largest bloc of Turkish voters support him and his party. It’s hard to deny that reality after Sunday’s local elections, which became something of a referendum on Erdoğan and his government.

The CHP was founded in 1923 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the modern Turkish secular state, and it’s still the chief leftist opposition party in Turkey, though it’s largely tainted by association with corrupt government and military-backed rule. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the party’s leader for the past four years, seems likely to face a challenge to his leadership following the party’s poor local election results. Though the CHP will remain competitive in Turkey’s major cities, there’s little chance it has enough strength to win the next presidential and parliamentary elections.

Photo credit to DHA.

One thought on “The fight for Turkey is between Erodganists and Gulenists”