The images from Taksim Square over the past week, culminating in conflict between protesters and Turkish police authorities, have stunned a global community that’s used to thinking of Turkey — and, in particular, Istanbul — as a relatively tranquil secular meeting point of East and West.![]()

Although I’ve not written much about Turkey through Suffragio, it’s a fascinating country that I was delighted to visit in 2010, at the height of the glory days of the government of its current (and now embattled) prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Ultimately, there are two questions at issue here: how to evaluate Erdoğan’s performance prior to the recent protests, on the one hand, and how to evaluate Erdoğan’s performance during and in response to the protests, on the other hand.

Although Western commentators have increasingly argued of Erdoğan’s move toward increasing Islamization and authoritarianism, I worry that those calls misunderstand the depth of Erdoğan’s support and the nature of what modern Turkey (it is, after all, a country that’s over 98% Muslim) has become today. But it is impossible to watch Erdoğan’s repression of basic political freedoms, such as his government’s recent moves to disrupt a planned May Day protest, and the ongoing brutal police response to the Taksim Square and increasingly, nationwide, protests without admitting that whatever legitimacy Erdoğan once enjoyed is rapidly dissipating, and Erdoğan, his government, Turkey’s president, Turkey’s military, and Turkey’s awakened — and rightfully angry — protest movement, are all trapped in a suddenly perilous standoff.

It’s all the more fragile given the ongoing civil war in Syria. Not only has the Erdoğan government been unsuccessful in persuading one-time ally Bashar al-Assad to pursue a more moderate course, the growing number of refugees from Syria within Turkey’s borders means that Turkey risks being drawn into a wider regional conflict (though, in one of the few humorous asides to the ongoing protests, Syria has now issued a travel warning for Turkey).

Erdoğan’s initial position was legitimate and democratic

When Steven Cook wrote in The Atlantic earlier this month, that ‘while Turkey is perhaps more democratic than it was 20 years ago, it is less open than it was eight years ago,’ I had two initial reactions. First and foremost, shouldn’t we care more, from a pure governance standard, that Turkey’s government is representative and responsive to its electorate than it hews to some Westernized standard of ‘openness’? What does ‘less open’ even mean? Secondly, when Cook laments Turkey’s ‘less open’ nature, he doesn’t equally lament that the European Union virtually slammed the door in the face of Turkey’s application to join the European Union in 2005, when despite the opening of negotiations for Turkish accession, it became clear any road for Turkey’s EU membership would be long and arduous. It may be difficult to remember today, but it’s a push that Erdoğan’s government made even more passionately than the governments that preceded it.

Turkey, let’s be clear, didn’t leave Europe. Europe left Turkey, which has focused on becoming a more important regional player in the Middle East in recent years.

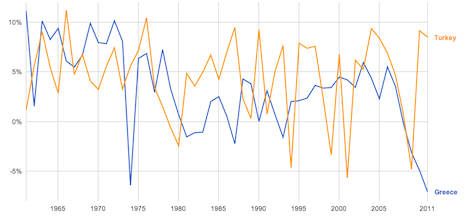

More importantly, from a day-to-day perspective for most Turks, Erdoğan ushered Turkey into a new era of economic reform and modernity, partly due to his enthusiasm to enter the European Union in his first term. But despite the futility of Erdoğan’s initial rationale, Turkey’s economic gains are real, the country certainly remains under much better economic stewardship than Greece or much of Europe:

But Cook, and similar analysts, I fear, are not placing enough weight on the fact that Erdoğan has delivered Turkey’s most responsive and democratically accountable government since the foundation of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923. And when I read critiques of Erdoğan that cast him as a modern-day ‘sultan,’ I have to cringe because it’s intellectually lazy for opponents to slap Orientalist labels on Erdoğan simply because they disagree with his policy choices.

The Economist on Sunday trumpeted a foreign diplomat who argues that ‘this is not about secularists versus Islamists—it’s about pluralism versus authoritarianism,’ though the question remains — pluralism compared to what? The governments that came before Erdoğan? Some Western fantasy of what Turkey’s government should be?

Erdoğan is neither a sultan nor a dictator, but the duly elected leader of Turkey’s government for over a decade, enjoying the repeated success of consecutive democratic victories in election after election.

Erdoğan, it’s critical to note, has a long record of support from voters — he was elected mayor of Istanbul in 1994, even though Turkey’s government convicted him merely for reciting an Islamic poem three years into his term). He then formed the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party), a mildly Islamist, socially conservative and economically liberal political party in 2001 and thereupon led it to a landslide victory in the November 2002 election.

Erdoğan won reelection in July 2007 with an even larger mandate, and he won a third term in June 2011 with a similarly wide margin. His party holds 327 seats in Turkey’s 550-member, unicameral Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (the Grand National Assembly of Turkey), and the AKP won the 2011 elections with 49.83% of the vote, even more than the 34% it won in 2002 and the 47% it won in 2007.

In its initial 2002 victory, the AKP ejected Bülent Ecevit from power, who headed the last-gasp coalition of an entrenched military-political elite (Ecevit himself served his first of four stints as Turkey’s prime minister in 1974), and the AKP won the largest democratic victory in nearly two decades on the strength of a coalition of the middle-class Muslims that dominate Turkey’s Anatolian heartland, many of whom welcomed a mildly Islamist government for the first time in Turkey’s history, and the urban liberals who had tired of a government whose military prioritized its secular nature over its democratic nature — and whose military had become a thoroughly corrupt ruling class in the process.

Kemalism: no reason for nostalgia

It’s vital to remember that prior to Erdoğan, Turkey had a political system that, despite regular elections, was wholly nationalist and secular, with ‘democracy’ guaranteed by the military under the vision of its founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (pictured above), who led the campaign for an independent Turkey in its war of independence of occupying allies after the spectacular collapse of the Ottoman empire after World War I. As Turkey’s first president from 1923 to 1938, Atatürk instituted what has become known as Kemalism in Turkey — he banned the wearing of the ‘fez’ and other accoutrements of what he thought of as backward in his single-minded pursuit of a modern Turkey. That focus led not only to the isolation of political Islam as a impossible movement in Turkey, but led to the fairly brutal treatment of Turkish Kurds, whose language was banned in the 1920s and who were not even permitted to be referred to as Kurds through much of the early decades of the Turkish republic (instead, Kurds were officially termed ‘mountain Turks’). That, in turn, spawned a relentless separatist conflict with the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (PKK, Kurdistan Worker’s Party), which initiated a violent campaign against the Turkish government in the early 1980s. Nonetheless, Atatürk is widely revered, to this day, as Turkey’s founding father, even if the system that he engendered is somewhat less celebrated — Erdoğan’s government, for example, banned YouTube in Turkey from 2007 until 2010, due to what Turkish authorities deemed attacks on Atatürk that ‘insulted Turkishness.’

In reality, Kemalism meant that Turkey marked its first three decades without any elections whatsoever and, after 1950, when Turkey finally allowed free election, anytime that the Turkish electorate voted for a government seen as too close to political Islam, the military would intervene to expunge the duly elected government from power, which happened at least once a decade between 1960 and 1997, when the military help engineer the fall of the government of prime minister Necmettin Erbakan, whose Refah Partisi (RP, Welfare Party) won the 1995 general election and is generally seen as the precursor to today’s AKP.

Fast-forward to 2013, and it’s clear that Erdoğan (pictured above) represents a broad majority of the Turkish population, and his power in the Grand National Assembly results from free and fair elections — he took power democratically, in contrast to the villains of the Arab Spring, such as Assad, former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, former Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali or even Bahrain’s king Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. That alone makes sloppy comparisons to the demonstrations at Tahrir Square facile and, ultimately, unfair to the arguments of Turkey’s protesters.

The chief opposition, the Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party), which Atatürk himself founded, is a broken party with support that’s withered to just Turkey’s western Aegean coast. In 2011, even after a leadership change and a renewed focus on social change, it barely won over 25% of the vote. It’s a party that many Turks believe belongs to a past era — even the protesters in Taksim show little enthusiasm for the CHP.

A new way for Turkey? Neither Kemalist nor Islamist

What’s become clear over the past month is that Erdoğan’s coalition has crumbled — the urban elites that helped propel him to power are falling away, and a new young generation is demanding even more political change. The unraveling of that coalition is, perhaps, one of the reasons why Erdoğan has been so keen recently to take policy positions that are targeted toward his socially conservative Islamist base. Though the West may wring its hands over recent legislation, for example, that limits the sale and consumption of alcohol in Turkey, it’s important to be mindful that, according to one survey, 83% of Turks don’t even drink alcohol. (For the record, here’s an excellent post — and Google map! — from Ottomans and Zionists explaining one aspect of the crackdown on alcohol in Istanbul). Even if you disregard that less than a century ago, the temperance movement in the United States successfully passed a constitutional amendment prohibiting alcohol, is the anti-alcohol legislation really so much different in kind than the anti-abortion legislation passed by Republicans in socially conservative U.S. states? No one’s calling the United States an authoritarian regime.

Although the median age of Turkey’s 75 million-strong population is older than Egypt’s, it’s still just 29 years old. So Turkey now has a full generation that grew up under Erdoğan’s rule which, in many cases, is nonetheless too young to remember the Kemalist era before it. For that generation, especially, in a world of Twitter, Facebook and instant news, it’s not enough that Erdoğan’s landmark 2002 election and subsequent rule marks an improvement in Turkish democracy in relative terms — it’s a generation that wants more freedom in absolute terms.

In contrast to the Kemalist system that Erdoğan preceded, especially in light of the three-year interregnum of torture, imprisonment and crackdown that began with the Turkish military’s 1980 coup, Erdoğan measures up incredibly well. There’s simply no comparison — the sins of the Erdoğan government pale in comparison to those racked up by the governments of the preceding decades. Predictably, Erdoğan has delivered heretofore unknown amounts of religious freedom in Turkey, where wearing the headscarf has become once again commonplace, despite a headscarf ban imposed on female public employees by the military government that took power in 1980 (and that had become a de facto ban on female employees in the private sector). The ban that remains in place despite an overwhelming vote in the Grand National Assembly to lift it in 2007, due to a 2008 ruling by Turkey’s constitutional court. Just last month, the PKK’s leader, Abdullah Öcalan, who has been imprisoned by Turkey since 1999, announced a PKK ceasefire following the Erdoğan government’s relaxation of anti-Kurdish laws, which included legalizing the public use of Kurdish and the restoration of Kurdish names of cities, and limited anesty for rank-and-file PKK fighters.

But when judged against the terms of international standards, which the youngest generation of politically aware Turks have come to expect, Turkey lags behind in both press freedom (Turkey has steadily fallen in the press freedom rankings from Reporters without Borders to 154th this year, and it imprisons more journalists than any country in the world) and, as has become increasingly clear as the Taksim and national protests have unfolded, freedom of speech and assembly as well.

How the protests have irreversibly damaged Erdoğan

Initially, the Taksim protests focused on the demolition of Gezi Park, near Taksim Square in downtown Istanbul, to erect a mosque and a shopping center in the style of an Ottoman-era barracks. Protesters opposed not only the destruction of increasingly rare green space in the developed city of Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city and its cultural and economic center, but the razing of the nearby neighborhood of Tarlabaşı, populated by relatively poorer Turks, including Kurdish refugees from eastern Turkey. The project is just one of several recent ones that change the face of Istanbul, including a new international airport and a third bridge across the Bosphorus.

There’s nothing necessarily authoritarian about Erdoğan’s political will to push forward with any of those, even though they may not be the most environmentally-friendly projects — U.S. presidents have pushed forward with broader plans on broader issues despite extreme — even constitutional — opposition (George W. Bush on the Iraq War, for instance, or Barack Obama on federal health care reform).

But whatever legitimacy Erdoğan may have initially enjoyed has been vanquished by his brutal crackdown against the protesters in Taksim Square. Whether you think Erdoğan was simply effecting reasonable policy decisions that are easily explained by public choice theory, or whether you think that Erdoğan is a closet Islamist who’s been waiting a decade to unfurl his true authoritarian colors, there’s no excuse for the crackdown on protesters. When over a thousand protesters have been injured and allegedly two protesters have been killed, no one is going to defend the violent dispersal of peaceful protesters. By escalating the situation with a violent response, Erdoğan has no one to blame but himself for the fact that the protests have now transformed from a local concern into the embodiment of long-simmering tensions at the heart of Turkish national identity.

The endgame

So where will the Taksim-initiated protests end? Erdoğan has already ordered police to withdraw from Taksim Square, though not necessarily from other sites of protest. Though protesters may believe that’s ‘too little, too late,’ and they are right about that, there may well be little that they can do to remove Erdoğan from office when he still appears to enjoy the support of the majority of the electorate.

Although it’s clear that Erdoğan’s political position is legitimate in a way that Mubarak’s never was, his government has consistently failed to get ahead of the protesters in the same way that Mubarak also failed to rise to the escalating level of protests. A well-timed retreat from the Gezi Park development would have gone a long way to satisfy Erdoğan’s critics initially, but the protests have now widened to such a point that Erdoğan won’t be able to evade lingering doubts even if he abandoned Gezi Park (a project he continues to defend, although he backed away Sunday from the shopping mall idea).

It’s not clear if an immediate volte–face on the national protests and an end to the clashes with police would satisfy critics at this point, so how does Turkey bring itself off the ledge?

- Emergence of a new political dynamic. Perhaps the most constructive — and maybe the most likely — path forward for Turkey is the gradual transformation of the demonstrations into the development of a more robust opposition. Whatever you want to say about Erdoğan, it’s clear that there’s no going back to the old coalition that worked so well in 2002, in 2007 and in 2011. The dynamic of Turkey’s electorate has changed so much that Erdoğan has irretrievably lost many of his former supporters — though, it’s important to stress, he’s not necessarily lost a majority of Turkish voters. Nonetheless, in a manner that’s unprecedented in the Erdoğan era, disparate groups — from liberals to socialists, from the young to the old, from gays to football hooligans to Kurds and Alevi Turks and Armenians — have come together in opposition to Erdoğan in a way that the CHP could never hope to emulate. Turkey will hold its first direct presidential election next year (Erdoğan is likely to run for the office, which will subsequently wield bolstered powers) and parliamentary elections sometime before June 2015, so that gives Turkey’s newly enlivened and united opposition 24 months to fashion an alternative vision and platform for Turkey’s future. That’s little consolation to the protesters whose lives were endangered by ferocious police attacks, but there’s no way that protests alone can simply force a duly elected government from office.

- Abdullah Gül to the rescue. Turkey’s president, Abdullah Gül (pictured above), reportedly intervened with the government to urge ‘sensitivity and maturity’ in response to the Taksim protests, and he may well have been instrumental in the government’s decision to withdraw police from Taksim. Gül served briefly as a caretaker prime minister in 2002 and early 2003, and later as Erdoğan’s deputy prime minister and foreign minister before he was elected president by Turkey’s Grand National Assembly in 2007. He’s always been viewed as a more cosmopolitan figure and a smoother operator than Erdoğan, despite the fact that his wife wears a headscarf. So it’s no surprise that he’s been a relatively more moderate voice in calling for restrain as Turkey’s head of state. Protesters are now chanting ‘Tayyip istifa‘ — ‘[Tayyip] Erdoğan resign!’ If Erdoğan’s position ultimately becomes untenable as prime minister, there would be no better person to deliver the message than Gül. Though it remains unlikely, no one could effect a more seamless transition to a post-Erdoğan government than Gül, and it remains a better option than a military solution.

- A military coup. If the protests worsen, if the image of an Istanbul and an Ankara in duress remain on the front page of the world’s newspapers, if Erdoğan doesn’t offer an olive branch to protesters, and if Gül cannot find a way to moderate (or even terminate) Erdoğan’s leadership, it’s not unthinkable that Turkey’s military could intervene to remove Erdoğan — they’ve done so in the past on the basis of much less cause. Notably, the military has remained aloof in the current dispute, and it’s been Turkey’s polices forces, not its military, that have clashed with protesters. Though the military’s wariness of the AKP has weakened considerably through a decade of coercion and the normalization of Erdoğan’s government, a military response is not outside the realm of possibility if matters worsen, which is one reason among many that Erdoğan and Gül should tread very carefully in the days to come.

Top photo credit to Daniel Etter, following photo credit to Haider Changezi via Twitter.

Good analysis, Kevin. Can’t think of anything you’ve left out–though I think the question of responsibility for the disaffection between Turkey and the EU is more complicated than you let on.

This is peculiarly uninformed comment:

“First and foremost, shouldn’t we care more, from a pure governance standard, that Turkey’s government is representative and responsive to its electorate than it hews to some Westernized standard of ‘openness’? What does ‘less open’ even mean?”

1: Could you please define what you mean by a “Westernized” standard of openness? Are you saying there is an Oriental standard? A Turkish standard?

2: As for what “less open” means, it’s fairly obvious — a less open civil sphere. Specifically:

-crackdown on the press and media, more generally.

-crackdown on opposition parties.

-crackdown on public protest.

None of those 3 elements of “less open” is particularly controversial or particularly “Western.”

It’s not fairly obvious to me why Turkey is ‘less open’ today, on whole, than it was eight years ago because ‘open’ is a pretty broad term. It’s a mixed bag. There’s absolutely no doubt that press freedom has suffered and freedom of assembly and expression have suffered. Erdoğan’s getting worse on this account, not better.

The Turkish economy is more open than it was eight years ago.

Religious freedom is stronger than it was eight years ago.

If you’re Kurdish, you certainly have a more open civil sphere than you did eight years ago.

Governments aren’t routinely turfed out of office by the Turkish military because they’ve deemed the government too Islamist.

To gloss over those elements in an otherwise alarmist piece on why Turkey is ‘slowly Islamizing’ imposes a normatively Western viewpoint that ‘Islamizing,’ in and of itself is a bad thing when that isn’t necessarily so. It’s not that Erdoğan hasn’t made Turkey less open, but he’s also made Turkey more open in other ways. So if you’re a pious Muslim or a Kurd or a businessman, you might think Turkey is more open today; if you’re a journalist or a secular liberal, you might think Turkey is careening toward Putin-style autocracy. And both constituencies could be right — Turkey could be simultaneously more open in some regards and less open in other regards. It’s just a much more complex narrative than ‘Turkey is Islamizing, therefore it’s less open.’

Moreover, the ‘the Islamization of Turkey’s political institutions will proceed apace’ because a majority of Turks seem to favor it — if not, they can reject Erdoğan in the 2014 presidential race and/or the AKP in the 2015 election. There’s more to a vibrant democratic system than just elections, as Erdoğan is learning this week, but mandates matter.

I know Steven Cook may seem like an antagonist du jour at the moment, but here’s a later piece from him that you may even find some points of agreement with:

http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139432/steven-a-cook/keep-calm-erdogan

Unless i’m mistaken, isn’t the AKP ruling Turkey in a coalition? If not, how does a political party govern a country with less than 50% of the popular vote (unless there’s massive gerrymandering)?

“No one’s calling the United States an authoritarian regime.” — Umm, how should I even begin to address this? Let me say this as a non-American: the US has charactertistics of an authoritarian state, both domestically as well as overseas, particularly its neo-imperial ’empire’ of militray bases and business-intellectual apostles of neo-liberal governance worldwide (Chicago School, anyone?). What the US is not, however, is autocratic. Yet.

“Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party), a mildly Islamist, socially conservative and economically liberal political party”

— We have words for this: A variant of neo-liberal government with ‘post-secular’ elements thrown in.