Unable to form a governing coalition with any of Turkey’s opposition parties after more than a decade of one-party rule, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s strategy for scrambling politics prior to the country’s return to polls on November 1 is becoming increasingly clear, and it’s a cynical maneuver that could ruin one of Erdoğan’s most important legacies.![]()

What’s clear is that Erdoğan and his chief lieutenant, prime minister and former foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu are determined to take back their majority in the 550-seat Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (Grand National Assembly), even if it means bending the rules of traditional democracy. With each passing day, the Turkish military’s intensifying engagement both against the Islamic State/ISIS and Kurdish militants within the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, Kurdistan Workers’ Party) seem designed to shake up Turkish politics enough for the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) to return to power without resorting to a governing coalition.

While there were already worrying signs that Erdoğan was attempting to harass Turkish media in the lead-up to the June campaign, he now seems to be going even farther by arresting and raiding the most critical voices in the press. As Erdoğan’s push against Kurdish militants increases, he has openly discussed persecuting all Kurdish politicians, even those with few ties to the PKK.

To understand what’s going on requires an understanding of the arithmetic of Turkish politics, especially because many polls show that voter preferences haven’t particularly changed since June.

* * * * *

RELATED: How Turkey’s Kurds became a key constituency in presidential election

RELATED: Coalition politics returns to Turkey after AKP loses majority

* * * * *

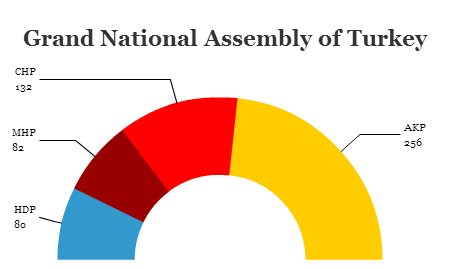

In the June 7 parliamentary elections, the AKP won around 41% of the vote. That’s far ahead of any of its opponents, but it wasn’t enough to secure a majority, let alone the supermajority that Erdoğan wants to revise the Turkish constitution and consolidate more power in the presidency.

The secular, center-left Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party) hasn’t been able to break through the AKP’s grip on power with ties to the old Kemalist regime associated with corruption, military coups and the repression of conservative Muslims and ethnic Kurds alike. Its leaders in the Erdoğan era have done little to rebrand the party to win support beyond the country’s Aegean coast, and its geriatric, charm-free leadership won just 25% of the vote.

The Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party), likewise, is also compromised by its ties to the old regime and to a controversial, right-wing Turkish ethnocentrism that looks back to the glory days of the Ottoman empire. It won just 16% of the vote.

The biggest change in the June election was the emergence of the Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP, People’s Democratic Party), a new party that brings together a bunch of left-wing groups and what was previously Turkey’s Kurdish-interest party. Under the magnetic leadership of Selahattin Demirtaş, a 42-year-old Kurdish human rights attorney, the party won around 13%, just enough to surpass Turkey’s 10% hurdle rate — enough to give Kurds, as a group, political representation in the national assembly for the first time in Turkish history.

Therein lies Erdoğan’s problem. In his first decade in power, when he was merely prime minister, Erdoğan probably did more for Turkey’s Kurdish minority than the previous 80 years of Turkish governments combined. His governments liberalized the use of the Kurdish language in the southeast of the country, in schools and for other everyday use. Increasingly, as the Kurdish region of northern Iraq became the only stable part of Iraq, Erdoğan worked with Iraqi Kurdish leaders both economically (to provide a new pathway for northern Iraqi oil) and politically (to secure Turkey’s borders, especially upon ISIS’s rise). Most importantly, Erdoğan entered peace talks with the PKK, giving many Kurds hope that politics, not guerrilla warfare, constituted the best way forward to secure equal rights and a measure of Kurdish autonomy. And for the first decade of Erdoğan’s regime, Kurdish voters typically rewarded him and the AKP with their votes.

That is, of course, until Demirtaş emerged as a rising star, not just for Kurds but for urban elites, secularists and others who believe Erdoğan’s creeping authoritarianism is no better than the militarist paternalism of the Kemalist regime that preceded it. When Erdoğan ran for the presidency last August (even with Demirtaş running), Kurdish votes help put him over the top for a majority victory in the first round. But when it came to the parliamentary elections, voting for the HDP gave Kurds a historic opportunity for representation within the Turkish state. In a sense, the HDP’s success is the natural conclusion of Erdoğan’s prior approach to Kurdish issues.

But that all changed when Erdoğan and the AKP found itself without a majority. So in late July, when the Turkish military agreed to launch airstrikes against ISIS, it also launched attacks against PKK targets, wildly escalating tensions after Kurdish militants broke a two-year ceasefire. In fact, Turkey has been far more aggressive against alleged Kurdish terrorists than against ISIS militants. It’s even odder because Kurdish militias in both northern Iraq and northern Syria are proving to be some of the most reliable US allies in the fight against ISIS (though the US government was clearly pleased to see Turkey, at long last, join the fight against ISIS).

The Islamic State’s most audacious attack on Turkey was the border city of Suruç, in the southeastern part of the country when most Kurds reside. So as ISIS threatens Kurdish regions in particular, Erdoğan immediately announced Turkish airstrikes on ISIS, but launched a much more intense bombing campaign against Kurdish fighters, many of whom were not interested in attacking the Turkish military but were instead aiding the Syrian Kurds and Iraqi Kurds fighting the Islamic State — and doing so more successfully than any other Western ally in the region.

By cracking down on the PKK (and, by extension, Turkey’s Kurds), Erdoğan is attempting to upend Turkey’s political calculus in two ways.

First, by taking a more muscular stance against Turkish Kurds, the AKP hopes to peel away votes from nationalist voters who might otherwise turn to the Nationalist Movement Party.

But more importantly, Erdoğan hopes to push Demirtaş’s popular new People’s Democratic Party back below the 10% threshold. To some extent, he might be able to scare some voters away from the HDP by harassing or arresting HDP politicians. But it increasingly seems like Erdoğan’s goal is to create so much tumult in southeastern Turkey that it depresses voter turnout altogether. To the extent Turkish airstrikes against ISIS draw additional attacks along the Turkish-Syrian border, that will only serve to destabilize the region, further discouraging turnout. The election won’t even take place for two more months, but Demirtaş already argues that eastern Turkey is in no condition to hold free elections:

“Under these circumstances [of violence], it is impossible to establish ballot boxes, hold the election or engage in election campaigning. I think this is the goal of the AKP [Justice and Development Party]. But if it really wants to, it can make sure those election circumstances are in place in one day,” Demirtaş said.

If the HDP wins just 10.1% (and polls show that it’s still on track to exceed 10%), it could win 60 seats in the national assembly. But if the HDP falls to just 9.9%, it wins exactly zero seats. Without the HDP taking up seats in the Turkish assembly, it’s much, much easier for the AKP to win a majority against. But to do so, it risks denying Kurds the political representation that they now (at long last) achieved, and, in turn, Erdoğan risks obviating all the work he’s done to repair relations with Turkey’s largest minority group. While that might effectively boost Demirtaş’s rising international profile, it could also benefit PKK-friendly hardliners if they can convince Kurds that Turkey’s rulers will never accept the more conciliatory, democratic Demirtaş approach.