Lebanon’s president Michel Suleiman left office on May 25, but even as the country struggles to contain the chaos — political, humanitarian and otherwise — that’s spilled over from Syria’s four-year civil war. ![]()

Earlier today, Nabih Berri, the speaker of Lebanon’s national assembly (مجلس النواب), scheduled the seventh vote since April 23, to elect Suleiman’s successor.

Like the last six ballots, there wasn’t even be a quorum for the vote. Berri has scheduled the eighth attempt for July 2.

* * * * *

RELATED: Lebanon’s parliament considers

presidential choice tomorrow

RELATED: In first ballot, Lebanon’s parliament fails

to elect new president

* * * * *

Given that it took ten months for prime minister Tammam Salam to form a new government in February, and that Salam’s unity government came together almost solely for the rationale of getting Lebanon through the presidential election and through a new electoral law and fresh parliamentary elections, there’s no telling how long the standoff could last — perhaps months or even well into 2015.

After former president Émile Lahoud left office in November 2007, it took another six month — until May 25, 2008 — to elect his successor, Suleiman (pictured above).

Though the Lebanese presidency is largely ceremonial, it’s a vital component of the fragile balancing of confessional interests in a country with 18 officially recognized ‘confessions’ — or religious groups. Lebanon’s president must be a Maronite Christian, while its prime minister must be a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of the Assemblée nationale (National Assembly) must be a Shiite Muslim. Of the 128 members of the National Assembly, 64 must be Muslim and 64 must be Christian.

In the meanwhile, Christian parties have said that they will boycott the national assembly’s sessions until a new president is chosen, arguing that the priority for Lebanon should be electing a new president, not routine legislation. That, in turn, makes it less likely that the Salam government can accomplish much of anything until Lebanon has a new president — and there’s no assurance that a new president will be in place in time for parliamentary elections scheduled (for now) to take place in November.

The problem is that Lebanon isn’t Belgium — on balance, it’s not great news for Lebanese governance that it has a caretaker government, with no hope of electing a president and no hope of holding parliamentary elections, which last took place in April 2009. That’s true in ‘normal’ times, but it’s especially true as Lebanon’s government works to hold off further violent spillover from the Syrian civil war, which has ignited sectarian tension in Beirut, Tripoli and elsewhere in Lebanon. The government is also struggling to accommodate over one million Syrian refugees currently living in Lebanon — that’s a staggering amount for a country that only had around 4.5 million people to begin with.

So why can’t Lebanon elect a new president?

Continue reading Suleiman is gone, and Lebanon still has no president

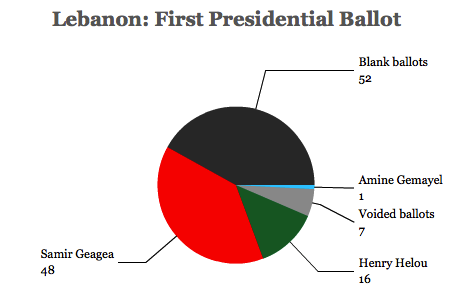

With the term of Lebanese president Michel Suleiman set to expire on May 25, the country’s 128-member parliament will convene tomorrow, April 23, for the first of what will likely be weeks of voting and negotiating to select a replacement.

With the term of Lebanese president Michel Suleiman set to expire on May 25, the country’s 128-member parliament will convene tomorrow, April 23, for the first of what will likely be weeks of voting and negotiating to select a replacement.