Photo credit to Roberto Monaldo / LaPresse.

Photo credit to Roberto Monaldo / LaPresse.

Italy’s presidential election functions more like a papal conclave than a direct election or even like a party-line legislative vote like the recent failed attempts to elect a new Greek president.![]()

The long-awaited decision today by Italian president Giorgio Napolitano to resign after nine years in office is not likely to result immediately in snap elections in Italy, as it did recently in Greece. Nevertheless, the resulting attempt to select Napolitano’s successor presents Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi with perhaps the most treacherous political task since taking office last February.

Napolitano’s legacy

Napolitano, at age 89, was anxious to step down after Italy relinquishes its six-month rotating European presidency this week. Elected president in 2006, Napolitano (pictured above, left, with Renzi), a former moderate figure within Italy’s former Communist Party, is Italy’s longest serving president, reelected to an unprecedented second seven-year term in 2013 when the divided Italian political scene couldn’t agree on anyone else after five prior ballots.

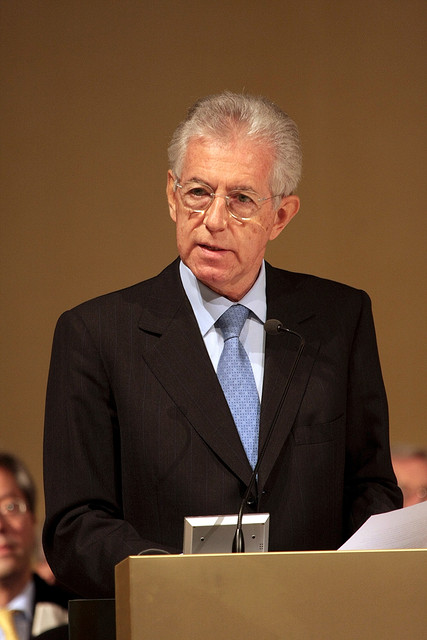

Critics refer to Napolitano as ‘Re Giorgio‘ (King George), but there’s little doubt that he was consequential during Italy’s financial markets crisis in late 2011 by nudging Silvio Berlusconi, who first came to power in 1994, out of office — seemingly once and for all. Napolitano’s behind-the-scenes maneuvering may have prevented Italy from the humiliating step of seeking a bailout from European authorities though his detractors argue that he circumvented the democratic process by engineering Berlusconi’s ouster and appointing former European commissioner Mario Monti as prime minister. Monti, who stepped down after 2013 national elections, largely failed to push through major economic reforms that many investors believe Italy needs to become more competitive, and that Renzi now promises to enact.

Napolitano, who will remain a ‘senator for life’ in the upper chamber of the Italian parliament, steps down with generally high regard from most Italians, who believe that he, in particular, has been a stabilizing force throughout the country’s worst postwar economic recession.

An opaque process to select a president

The process to appoint his successor involves an electoral assembly that comprises members of both houses of the Italian parliament, plus 58 additional electors from the country’s 20 regions — a total of 1,009 electors. Within 15 days, the group must hold its first vote, though it may only hold a maximum of two voter per day. For the first three ballots, a presidential candidate must win a two-thirds majority. On the fourth and successive ballots, however, a simple majority of 505 votes is sufficient. Continue reading A guide to Italy’s post-Napolitano presidential puzzle