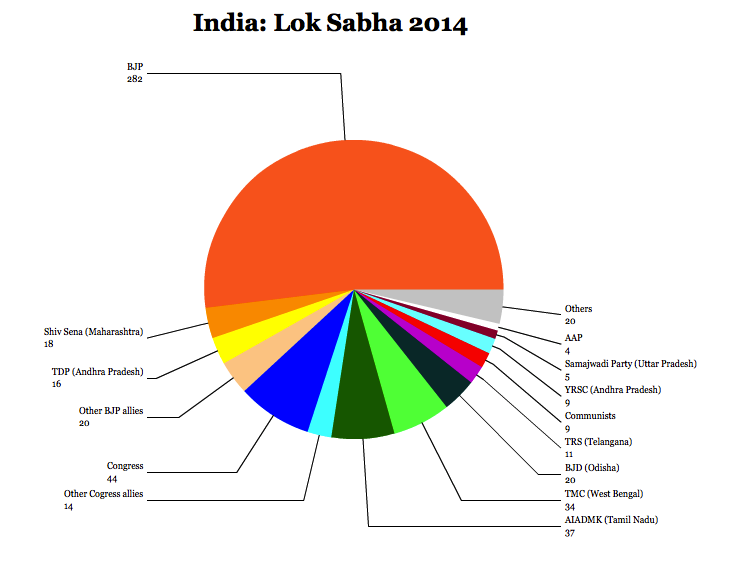

When he was campaigning across India in the leadup to his overwhelming victory in the 2014 general election, prime minister Narendra Modi often proclaimed that development, more than Hindu nationalism, would behis government’s priority.![]()

Pehle shauchalaya, phir devalaya. Toilets first, temples later.

Indeed, throughout this spring’s local election campaigns in five states across India, Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) emphasized development, economic reforms and defended the November 2016 ‘demonetisation’ effort, all neatly summed up in the slogan — sabka saath, sabka vikas, essentially ‘all together, development for all.’

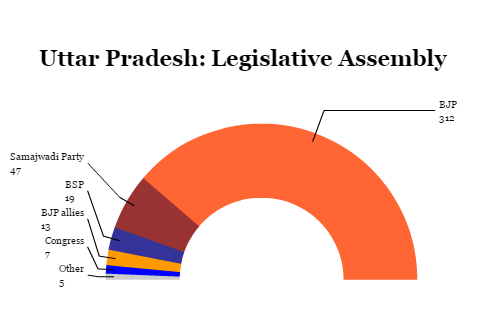

It worked: the BJP easily won elections in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, and it did well enough to form new governments in Goa and in Manipur. (In the fifth state, Punjab, the BJP has a negligible presence as the junior partner of a Sikh-interest party that last week lost a 10-year grip on power).

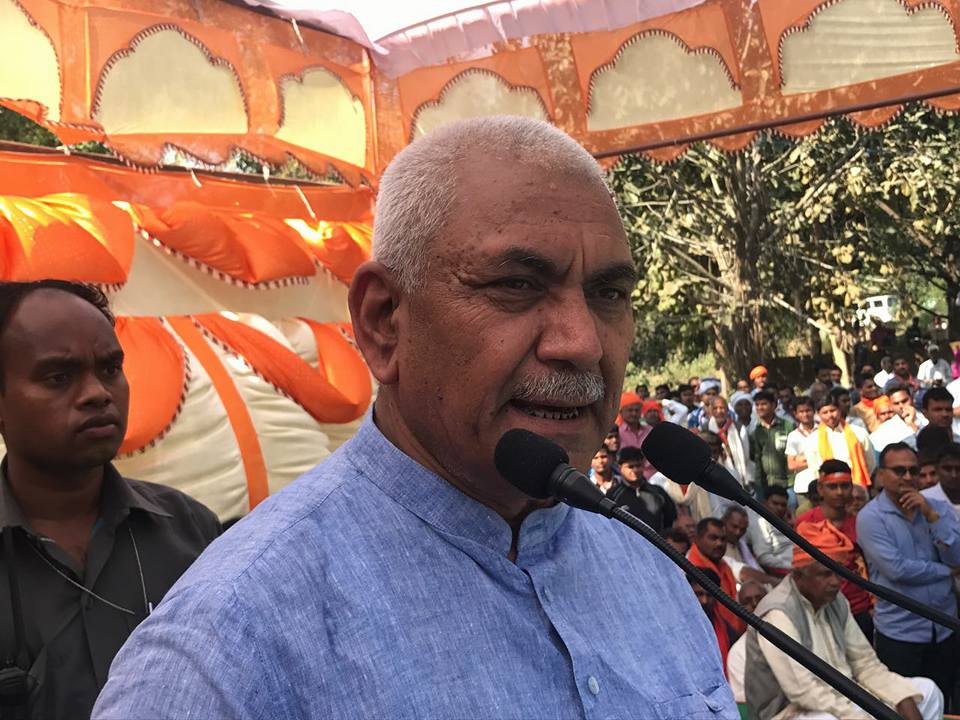

But the Modi brand of ‘toilets over temples’ seemed to change Saturday, when the BJP announced that Yogi Adityanath would serve as Uttar Pradesh’s new chief minister.

* * * * *

RELATED: Modi sweeps state elections in Uttar Pradesh

in win for ‘demonetisation’

* * * * *

The 44-year-old Adityanath, a local priest who dresses in saffron robes, has been a member of India’s parliament since 1998, representing the Gorakhpur district in eastern Uttar Pradesh.

He will now lead a sprawling north Indian state of over 200 million people; indeed, a state more populous than all but five countries worldwide. Uttar Pradesh, sometimes marred by religious violence in the past, and it’s somewhat poorer than the average Indian state. In fact, its per-capita GDP is lower than every other state in India (except for impoverished, neighboring Bihar) and barely more than one-third that in Modi’s home state of Gujarat.

Though many of the BJP’s supporters are motivated by Hindutva — the idea of bringing Hindu nationalism and Hinduist morals and precepts into government, the Modi wave of 2014 (and 2017) rests on the idea that Modi can implement the kind of economic reforms and development policy to make Uttar Pradesh more like the relatively prosperous Gujarat.

To that end, many Indian commentators expected the BJP to call upon an experienced statesman to head the new government in Uttar Pradesh. Home minister Rajnath Singh, who briefly served as the state’s chief minister from 2000 to 2002, or the younger communications and railways minister Manoj Sinha, both of whom are among the most popular and successful members of the Modi government, typically topped the list of potential leaders.

By contrast, Adityanath doesn’t have a single day of executive or ministerial experience. He is a controversial figure, to say the least. In his first day as chief minister, he spent more time talking about shutting down slaughterhouses, a top priority for Hindu nationalists who believe that cows are sacred creatures, than about the nuts-and-bolts policy details, despite promising that development would be his top focus.

In short, the new chief minister is the bad boy of Hindu nationalism, a man who’s been charged with crimes as serious as attempted murder, rioting and trespassing on burial grounds. He once claimed Mother Teresa was part of a conspiracy to Christianize India, threatened one of the leading Muslim Bollywood film stars and accused Muslim men of waging ‘love jihad’ against Hindu women. Among his more moderate provocations was a recent threat to place a statue of Ganesha in every mosque in Uttar Pradesh. Continue reading Adityanath, Uttar Pradesh’s newly minted chief minister, is the bad boy of Hindu nationalism