When he was campaigning across India in the leadup to his overwhelming victory in the 2014 general election, prime minister Narendra Modi often proclaimed that development, more than Hindu nationalism, would behis government’s priority.![]()

Pehle shauchalaya, phir devalaya. Toilets first, temples later.

Indeed, throughout this spring’s local election campaigns in five states across India, Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) emphasized development, economic reforms and defended the November 2016 ‘demonetisation’ effort, all neatly summed up in the slogan — sabka saath, sabka vikas, essentially ‘all together, development for all.’

It worked: the BJP easily won elections in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, and it did well enough to form new governments in Goa and in Manipur. (In the fifth state, Punjab, the BJP has a negligible presence as the junior partner of a Sikh-interest party that last week lost a 10-year grip on power).

But the Modi brand of ‘toilets over temples’ seemed to change Saturday, when the BJP announced that Yogi Adityanath would serve as Uttar Pradesh’s new chief minister.

* * * * *

RELATED: Modi sweeps state elections in Uttar Pradesh

in win for ‘demonetisation’

* * * * *

The 44-year-old Adityanath, a local priest who dresses in saffron robes, has been a member of India’s parliament since 1998, representing the Gorakhpur district in eastern Uttar Pradesh.

He will now lead a sprawling north Indian state of over 200 million people; indeed, a state more populous than all but five countries worldwide. Uttar Pradesh, sometimes marred by religious violence in the past, and it’s somewhat poorer than the average Indian state. In fact, its per-capita GDP is lower than every other state in India (except for impoverished, neighboring Bihar) and barely more than one-third that in Modi’s home state of Gujarat.

Though many of the BJP’s supporters are motivated by Hindutva — the idea of bringing Hindu nationalism and Hinduist morals and precepts into government, the Modi wave of 2014 (and 2017) rests on the idea that Modi can implement the kind of economic reforms and development policy to make Uttar Pradesh more like the relatively prosperous Gujarat.

To that end, many Indian commentators expected the BJP to call upon an experienced statesman to head the new government in Uttar Pradesh. Home minister Rajnath Singh, who briefly served as the state’s chief minister from 2000 to 2002, or the younger communications and railways minister Manoj Sinha, both of whom are among the most popular and successful members of the Modi government, typically topped the list of potential leaders.

By contrast, Adityanath doesn’t have a single day of executive or ministerial experience. He is a controversial figure, to say the least. In his first day as chief minister, he spent more time talking about shutting down slaughterhouses, a top priority for Hindu nationalists who believe that cows are sacred creatures, than about the nuts-and-bolts policy details, despite promising that development would be his top focus.

In short, the new chief minister is the bad boy of Hindu nationalism, a man who’s been charged with crimes as serious as attempted murder, rioting and trespassing on burial grounds. He once claimed Mother Teresa was part of a conspiracy to Christianize India, threatened one of the leading Muslim Bollywood film stars and accused Muslim men of waging ‘love jihad’ against Hindu women. Among his more moderate provocations was a recent threat to place a statue of Ganesha in every mosque in Uttar Pradesh.

Adityanath has spent much of his career on the outs with the BJP because many of the party’s elder statesmen found Adityanath’s Hindutva far too extreme. It’s a staggering move on the BJP’s part, and it puts many of Modi’s cheerleaders in a tough position. In the most charitable light, Adityanath’s selection proves that temples are just as important to Modi as toilets. It gives little cover to Modi’s moderate defenders, who have cautioned patience in hopes of deep economic reforms that could lift hundreds of millions of Indians into the middle class. Modi’s record so far has been imperfect. But even if you don’t give Modi any credit or goodwill for the anti-corruption aims of his ‘demonetisation’ effort last November, he’s still liberalized foreign investment laws and reduced interstate transactions costs with the landmark Goods and Sales Tax reform last year — despite a hefty protectionist wing within his own BJP.

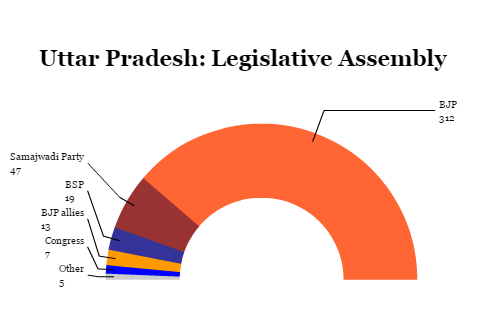

The most amazing part about Adityanath’s ascent is that, as in past contests, the BJP didn’t even bother naming a chief ministerial candidate in the lead-up to the voting, which took place in staggered rounds in February and March. In a lopsided four-way contest, the BJP managed to split the anti-Modi opposition (much of which consisted of lower classes, Muslims and other minorities) and win nearly 40% of the vote. That, in turn, was enough to propel the BJP to a massive supermajority in the state’s legislative majority that surprised even some BJP supporters, displacing three once-powerful forces:

- The Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), once the most powerful national party in Indian politics, reduced to a shell of its former self in 2014 and again in 2017 in Uttar Pradesh under the disastrous and ineffective leadership of Rahul Gandhi, a scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty that has controlled the party since independence.

- The Samajwadi Party (SP, समाजवादी पार्टी), a leftist regional party that controlled the state’s government from 2012 until last week under chief minister Akhilesh Yadav — and that suffered from infighting over a controversial alliance with Congress and a family spat between Akihlesh and his father, Mulayam Singh Yadav, the party’s founder and himself a former chief minister.

- The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP, बहुजन समाज पार्टी), which managed to unite upper-caste Brahmins, lower-caste Dalits and Muslims in 2007 when its leader Mayawati took power.

All three parties wilted in 2017 against Modi’s saffron machine.

Opposition figures and the Indian media are, not unpredictably, blasting the choice as hubristic, declaring it the last rites for Nehruvian secularism, mocking the idea that Indians should ‘give him a chance.’

Opposition figures and the Indian media are, not unpredictably, blasting the choice as hubristic, declaring it the last rites for Nehruvian secularism, mocking the idea that Indians should ‘give him a chance.’

One theory is that Modi (and Shah) realize their truly big test will come in 2019, when the BJP government seeks reelection nationwide. Elevating Adityanath to the head of Uttar Pradesh’s government forces one of the Hindu right’s most potent flamethrowers into a position of responsibility. Another theory is that, at the very least, Adityanath will motivate the Hindu base to work that much harder for Modi in 2019. Considering the glacial pace of any economic reforms, it was always going to be difficult for Modi to effect radical change in five years. By stoking communal passions, Modi can depend on an engaged and enthusiastic Hindu nationalist base in two years’ time. Perhaps Modi will find a way — as in Madyha Pradesh 15 years ago — to replace a firebrand chief minister (Uma Bharati, who lasted less than nine months) with a more pragmatic one (Shivraj Singh Chouhan, who took power in 2005 and governs to this day).

But in the meanwhile, Modi and Adityanath, both of whom have spotty records in their past with respect to communal violence, will have to work doubly hard that stoking communal passions doesn’t lead to riots — or worse. Notably, though the BJP won 312 seats in the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly, the party didn’t field a single Muslim candidate in a state where 18% of the population is Muslim (and now, quite alarmed at the rise of Hindu nationalism). Among the most smoldering controversies in the state is resolving the Ayodhya dispute, after 200,000 rioters destroyed the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya in 1992 in hopes of erecting a Hindu temple in its place, long believed to be the site of the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama.