With India’s massive nine-phase election now underway, what happens if Narendra Modi doesn’t quite win a majority in India’s parliament?![]()

Everyone believes that Modi, the longtime chief minister of Gujarat, and his conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) are headed for a historic victory. But that might not be enough — and if history is any guide, it won’t be enough, even taking into account the seats of the BJP’s coalition partners in the National Democratic Alliance (NDA).

That could mean that India’s ‘Third Front,’ a motley group of regional and Marxist/socialist parties, could team up with the remnants of the center-left Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) and the few parties that remain in the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). India has had Third Front governments in the past, but it’s a path that traditionally leads to acrimony, dysfunction and, sooner rather than later, new elections.

But if the BJP performs as well as polls widely suggest it might, there could be no doubt that the BJP (and Modi) have a stronger mandate to govern India and a stronger claim on forming the government than a rag-tag coalition of a dozen or more parties.

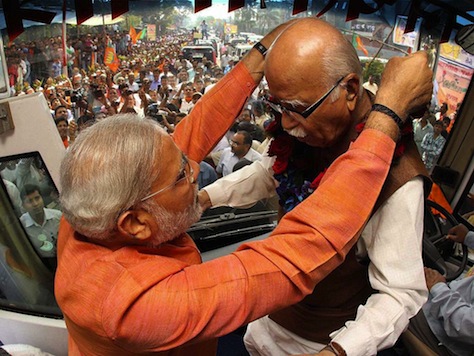

In that scenario, the BJP may be forced to turn to additional parties — and their price for support might require that the BJP jettisons Modi as its prime minister. That’s when things get really interesting, and it’s why the internal rifts inside the BJP over the past two years will become so important if and when the BJP/NDA wins the election with less than an absolute majority. In particular, it means that the rift between Modi and the elder statesman of the BJP, Lal Krishna Advani (pictured above, left, with Modi) could determine the identity of India’s next prime minister.

Why the BJP — and the NDA — probably won’t win an absolute majority

The problem is that Modi might, even in a historic victory, fall many seats below the 272 threshold he’ll need for a majority in the Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the lower house of India’s parliament.

There are at least three reasons for that.

A historical BJP ceiling. The ceiling for the BJP’s support, historically, has been lower than Congress’s. In its best-ever performance in February 1998, it won just 182 seats (giving the NDA a total of 254 seats). In the following election in September/October 1999, it won 180 seats (the NDA total was 270 seats). Historically, the BJP has had trouble winning much support in southern India (or really, outside the ‘Hindi’ belt of north-central India), among dalit and other low-caste constituencies, and among Sikhs, Muslims and other religious minorities. A ‘landslide’ for Congress means it can command an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha; a ‘landslide’ for the BJP has meant something much different.

The rise of regional parties. As Congress’s national hegemony faded over the years since independence, it’s given new life to any number of regional parties that appeal to many different combinations of regional, religious, caste or class identity. For example, in 1998 and 1999, the BJP could be reasonably assured of winning up to half the Lok Sabha seats from Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. Since the 1990s, however, two competing regional parties had edged both the BJP and Congress out of power, which are now considered the third and fourth parties in the state. Today, if the BJP wins between 30 and 40 seats (out of 80) in the state, it would be considered a victory. But that, of course, makes it harder to reach 272.

The NDA’s collapse. The final point worth noting is that the NDA has been reduced from a relatively strong coalition to a withered band of regional hangers-on. In 1999, the Tamil Nadu-based All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK, the All India Anna Dravidian Progress Federation) pulled out of the NDA, thereby collapsing prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government. But the BJP’s allies in the 1999 election still contributed 90 seats to the NDA coalition. Among the seven parties that currently join the BJP in the NDA, they hold 23 seats, and 11 of those come from Shiv Sena (SS, शिवसेना), a controversial, Maharashtra-based, hard-right Hindu nationalist party. In total, the seven parties are projected to win around 30 seats in 2014 — maybe 40 seats if the BJP is optimistic.

Notably, the Janata Dal (United) (JD(U), जनता दल (यूनाइटेड)) of Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar pulled out of the NDA last summer in protest of Modi’s record as it relates to the 2002 Gujarati riots and his government’s treatment of Muslims.

How the BJP could get to 272

So what happens if Modi and the BJP emerge as the largest force in the Lok Sabha but fall somewhat short of 272 seats?

The BJP would have to build bridges to the remaining regional parties to build a working majority — with regional leaders like Nitish Kumar, for example, who are already opposed to Modi becoming prime minister.

In order to win over those additional parties, many of which lean to the left and many of which appeal to vastly different constituencies than the BJP, their leaders could demand that the BJP find a new prime ministerial candidate if Modi is deemed too controversial.

There’s some precedent here. In 2004, when Congress won a surprise victory, its leader, the Italian-born Sonia Gandhi, thought that becoming prime minister would be too difficult, she instead turned to Manmohan Singh, the former finance minister.

The Advani-Modi rivalry

In the 1990s, Advani led the BJP’s campaigns, but it was Vajpayee who ended up as prime minister from 1998 to 2004. Advani’s ties to a Hindu nationalist campaign that ultimately led to the destruction the Babri Mosque in 1992 (and led to the deaths of 2,000 Muslims in riots across India), and Advani’s generally more hardline views on the role of Hindutva — Hindu values in government — made him too controversial for the top job and he instead became home minister and, eventually, deputy prime minister.

Throughout the years, Advani became the elder statesman of the BJP. Today, at age 86, he’s become less controversial as the memory of the Babri Mosque has faded — and Modi’s role in the Gujarati riots in 2002 remains unclear and the most contentious issue in the Indian election campaign.

As Modi slowly emerged as the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate and the strongest figure to lead the BJP campaign in 2014, it clearly ruffled Advani, who hoped to make one last attempt to become India’s prime minister. Throughout the campaign, Modi and his small cohort of aides have increasingly sidelined the old guard’s leadership, and it’s led to some of Modi’s most awkward moments in the national spotlight.

When Modi became the BJP’s campaign chief in June 2013, Advani resigned all of his positions in the party in a huff the following day. Modi and other BJP grandees scrambled to bring Advani back into the fold during what was supposed to be an otherwise triumphant party gathering in Goa — and Modi publicly met with Advani (pictured above) to demonstrate BJP unity. Though Advani rescinded his resignations a day later, the damage was done — and it showed how wide the gulf had become between the BJP’s old and new guards.

Earlier this spring, Advani brought that tension back to the forefront when he picked a fight with Modi over which constituency he would contest in the election. Advani (possibly) wanted to contest Bhopal constituency, in the state of Madhya Pradesh, instead of the Gandhinagar constituency, in the state of Gujarat, a seat that Advani has held since 1998. After another round of very public sniping, Modi’s team made it clear that it was Advani’s choice. Advani ultimately chose Gandhinagar, but the message was clear.

Advani’s initial choice of Bhopal highlighted his ties to chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan, another three-term chief minister in Madhya Pradesh that Advani has often praised in the past. The subtext, of course, is that Modi’s not the only successful three-term chief minister in the BJP.

Last weekend, Modi and Advani appeared together in Gandhinagar, but even then, Advani’s remarks seemed designed to rankle:

On the eve of BJP’s foundation day, the party’s founding father and senior leader L K Advani launched his campaign in Gandhinagar Saturday, backed by Narendra Modi and amid chants of “Ab ki baar, Modi sarkaar”. With his children Pratibha and Jayant by his side, the six-time MP from Gandhinagar, who filed his nomination Saturday, chose the occasion to clarify Modi was not his “protege” and said that he saw him as a “brilliant events manager”.

Though many of the incoming BJP deputies will be loyal to Modi, and though the ‘Modi wave’ will almost certainly be responsible of the BJP’s success this election cycle, there’s a possibility that the BJP won’t be able take power if its potential coalition partners refuse to do business with Modi.

That’s, of course, what Advani is counting on.

There’s a chance, however slim, that he could still wind up as the BJP’s backup choice for prime minister. Due to his tantrums against Modi’s rise, that’s less likely than it might otherwise been. Advani, too, would be 91 years old at the end of a full five-year term.

But even if he can’t engineer his own rise, he might still be able to promote one of his allies, like Singh Chouhan or the leader of the BJP’s caucus in the Lok Sabha, Sushma Swaraj — instead of an individual closer to Modi, such as Arun Jaitley, the leader of the BJP’s caucus in the upper house, the Rajya Sabha.

A possible compromise candidate is the BJP party president, Rajnath Singh, who is close to both Modi and Advani and who has often played the role of peacemaker, most recently over the Gandhinagar fight.

Make no mistake — if the BJP finds itself somewhat short of a majority, the Modi-Advani fights of the past year will look like afternoon tea in contrast to the crippling fight that could follow within the BJP.

a http://canadapharm24h.review view