Narendra Modi’s strongest argument in his quest to become India’s next prime minister is the record of economic growth in Gujarat, where he has served as chief minister since 2001 — and the promise that Modi can unlock the same kind of growth nationally. ![]()

There’s no doubt that Indian GDP growth has slowed — despite bouncing back from the 2008-09 global financial crisis with 10.5% growth in 2010 on the strength of a surge of investment in the developing world, India has struggled with much lower growth over the past three years. That’s one of the reasons that the governing center-left, governing Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) is so unpopular as it tries to win a third consecutive term in India’s April/May parliamentary elections.

But what is the ‘Gujarat model’? Can Modi really claim that his government’s policies are responsible for the superior Gujarati economic performance?

What’s more, even if Modi’s claims do hold up, is the Gujarat model so easily replicable that he will be able to implement nationally in the likely event that he becomes India’s next prime minister?

Though Modi and his center-right, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, or भारतीय जनता पार्टी) lead polls in India’s election campaign, the answers to those questions will determine the success — or failure — of any future Modi-led government.

‘Vibrant Gujarat’

Gujarat is a state of just over 60 million people on the west-central coast of India, bordering Pakistan’s Sindh state. Most of its residents speak the Gujarati language, and the state came in 1960 when India’s national government divided the former state of Bombay, part of a wider movement to reorganize Indian states on the basis of language. Historically, Gujarat’s geography has meant closer ties to Persia and the Arab world, though it’s not always been the most harmonious region of south Asia. Demographically speaking, it’s a bit more Hindu (89% of the population) than the rest of India (around 80.5%), though it has a significant Muslim minority, around 9% of the population. Gujarat has somewhat of a history of Hindu-Muslim tensions, stretching back to a series of deadly riots in 1969 and, most recently, riots in 2002 that continue to haunt Modi’s national ambitions. Critics say that his government did little to stop the violence, and many other critics argue that Modi and his BJP brethren were responsible for inciting the killings of around 1,000 Muslim Gujaratis.

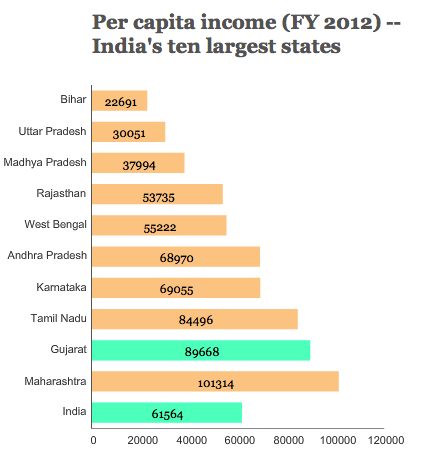

It’s undeniably true that Gujarat’s economy is one of the strongest in India, and the state has posted higher growth rates than the national GDP growth rate since 2001 — in Modi’s decade-plus as chief minister, Gujarat has grown by about 10% annually. Gujarat is ranked tops when it comes to economic freedom within India. The state’s per capita income outpaces not only the national average, but ranks near the top among India’s ten most populous states:

But Gujarat’s economy has always been more developed than much of the rest of India’s, and Gujarat has always had a tradition of entrepreneurism. Three years ago, The Economist called Gujarat the ‘Guangdong’ of India, favorably comparing it to the Chinese province that’s become a manufacturing and export engine over the past three decades. Gujarat is responsible for much of India’s oil refining, it is a net exporter of electricity, and its paved roads, robust energy grid and other infrastructural capacity induces foreign investment.

Gauging Modi’s performance

So how much of Gujarat’s economic growth over the past decade is due to its preexisting advantages, and how much is due to Modi’s efforts?

The record is mixed, because Modi inherited an economy with strong fundamentals. But Modi has also pursued aggressive, economically liberal policies to develop the Gujarati economy’s potential. Modi, for example, privatized the construction of state highways that form some of India’s most developed infrastructure. He’s developed more robust power grids to benefit a growing agricultural sector in rural Gujarat. Above all, he’s aggressively attracted the gleam of investors both domestic and foreign.

Part of Modi’s skill is administrative. He’s a decisive policymaker who governs with a relatively trim hierarchy. For example, Modi himself has served as Gujarat’s minister for petrochemicals, ports, industries and energy. Though that may be good for cutting through India’s seamlessly untamable bureaucracy, critics worry that Modi has little tolerance for dissent.

Some of Modi’s skill is in the marketing of Gujarat, such as the summit Modi hosts every two years for entrepreneurs that has become as much about boosting Modi’s image as Gujarat’s climate for investment that have become India’s miniature version of Davos. At age 63, he’s 20 years older than Rahul Gandhi, who is leading the Congress campaign, but Modi has embraced YouTube, online social networking and other new technologies to build the Modi brand in a way that could draw record support from young voters. In the 2012 state elections in Gujarat, Modi’s campaign projected a three-dimensional holographic avatar to allow him to campaign simultaneously in rallies throughout the state.

On this metric, Modi is clearly strong — it’s almost impossible to overstate the enthusiasm with which the Indian business class supports Modi for prime minister. Ratan Tata, the former chairman of the Tata Group, one of the largest companies in India and perhaps its most well-known, famously said of Modi: ‘If he says it will be done, it will be done.’

Though Gujarat is a darling of the investment class, its southern neighbor, the state of Maharashtra (where Mumbai is located), attracts significantly greater foreign direct investment — as do Delhi, Karnataka (where Bangalore is located), Andhra Pradesh and Tami Nadu.

Despite arguments from former Delhi chief minister Arvid Kejriwal, the leader of the strongly anti-corruption Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी), Modi has a relatively spotless record on corruption. It contrasts well to a dozen or more scandals that have marred Congress’s decade in power, including 2011’s spectacular 2G telecom spectrum scandal that cost the Indian government up to $7 billion and the 2012 Coalgate scandal that left India suffering from power brownouts as a result.

Critics argue that Modi’s branding efforts of Gujarat (and himself) are hardly an economic platform. They point to social indicators in Gujarat that could be much better, especially with respect to health and education. Despite Gujarat’s relative wealth, the literacy rate is just 79.3%, still slightly above the national average (74%), but lagging much further behind the top performer, Kerala (93.9%). Perhaps even more troubling is the infant mortality rate, which is only slightly above average, though Gujarat, like the rest of India, has marked improvements over the past decade.

Bihar, once the poster child for poor governance and poverty in India, has achieved even better economic growth than Gujarat over the past decade under chief minister Nitish Kumar, a former BJP ally. But while Bihar’s economy improved from a much more miserable starting point, Kumar has earned plaudits for balancing economic growth (in 2012-13, Bihar’s GDP grew by nearly 14.5%) with greater social welfare spending.

The Gujaratization of India?

Even giving Modi generous credit for the state of the Gujarati economy today, there’s plenty of skepticism that he can transform the rest of India, given the economic and cultural disparity of a country with over one billion citizens that straddles an entire subcontinent.

As noted above, Modi governs a state that already had a relatively developed infrastructure. Though Ahmedabad, the largest Gujarati city, is India’s fifth-most populous city, Modi hasn’t had to deal with the same kind of urban issues that Mumbai or Delhi face, and Gujarat doesn’t have nearly the population density of much of the rest of northern India.

The rest of India faces more severe economic challenges — poverty, corruption, lack of infrastructure, lingering statism, onerous regulation — that are much more severe than the conditions Modi inherited in Gujarat. In that regard, Modi will be no more able to replicate Gujarat’s unique economy in, Uttar Pradesh or West Bengal than a governor of California could, as US president, replicate Silicon Valley’s magic in Appalachia.

Moreover, if there’s one lesson that Indian voters should have learned from a decade of government under prime minister Manmohan Singh, it’s that past performance isn’t always indicative of future results. Singh, who as finance minister in the early 1990s delivered the most significant series of privatization and liberal economic reform in India’s post-independence history, followed up as prime minister with only meager, eleventh-hour measures that fall far short of the scope of his previous reforms.

What’s more, resistance to further reform comes not only from within Congress, but also from the BJP, which have blocked Singh from pursuing additional reforms. Even if Modi can command the discipline of his entire party as prime minister, it still might not be enough to effect his vision for transforming India’s economic policy. Though projections show that Modi and the BJP are poised for victory, the BJP may win just 180 to 200 seats in the 545-member Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the lower house of the Indian parliament, and the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance may win just 220 to 250 seats. That falls well short of the 272 majority mark, meaning that the BJP’s agenda may be held captive by local and minor parties, which the BJP will need to form a (likely unwieldy) coalition government.

Photo credit to PTI.