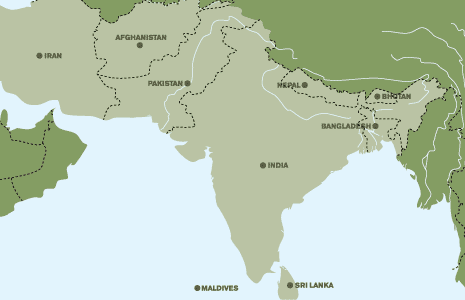

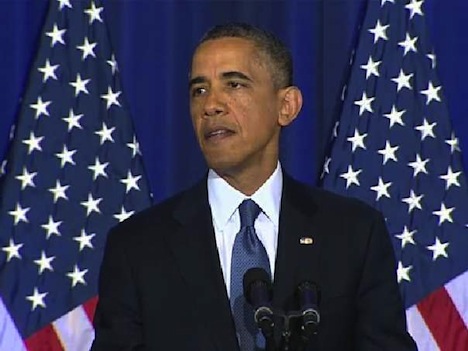

Four panelists discussed whether the United States military should leave Afghanistan at the end of 2014, as currently planned by the administration of U.S. president Barack Obama Thursday evening at a debate sponsored by the McCain Institute (founded in 2012 in cooperation with Arizona State University and, yes, U.S. senator John McCain was in attendance).

The panel included a wide range of voices, including the American Enterprise Institute’s Fred Kagan, The Atlantic‘s Steve Clemons, Ken Roth of the Human Rights Watch, and the RAND Corporation’s Seth Jones, whose 2010 book on the Afghan war, In the Graveyard of Empires: America’s War in Afghanistan, remains a must-read touchstone for understanding the U.S. effort in Afghanistan even today.

Whither Karzai?

The underreported issue is what exactly Afghanistan’s government will look like at the end of 2014 when U.S. troops are supposed to leave — and that, to paraphrase Robert Frost, will make all the difference.

It’s one of the most crucial puzzle pieces for Afghanistan’s future, both in relation to deeper U.S. political engagement with Afghanistan, as well as the U.S. decision on its military footprint in the country after 2014. After all, it’s going to be much easier for the U.S. to disengage militarily if it’s doing so in the context of an Afghan government that’s committed to the rule of law and nation-building and that can also stand on its own in the absence of U.S. forces.

As such, the presidential election currently scheduled for April 3, 2014 should determine the regime with which the U.S. government will be negotiating the transformation of its current military-heavy relationship with Afghanistan.

But for now, incumbent Afghan president Hamid Karzai is stepping down after two consecutive terms in office — he is constitutionally barred from seeking a third term in office.

That means, as U.S. troops draw down in permanent numbers, the U.S. government will not only be dealing with a new civilian government in Afghanistan, but a government without Karzai, the only Afghan leader that U.S. policymakers have ever really known since the U.S. military removed the Taliban government in autumn 2001. Karzai was quickly selected as interim president and, thereafter, won reelection in the (somewhat imperfect) October 2004 and August 2009 presidential elections.

So while the official timetable suggests an election around 13 months from now that will lead to Afghanistan’s first peaceful transfer of national power set to take place weeks before U.S. troops permanently withdraw, color me skeptical.

It seems to me that the United States can either secure the integrity of the current withdrawal timetable or the current Afghan electoral timetable, but certainly not both.

That the McCain Institute is even hosting a panel to discuss the option of a significant U.S. military force in Afghanistan beyond 2014 is a testament to the fact that the 2014 drawdown date is written in pencil, not ink. And if the mayor of New York City can find a way to evade term limits to seek a third consecutive term, I’m sure the U.S.-backed president of Afghanistan can do the same.

Consensus for greater U.S. political engagement

One thing upon which all of the panelists more or less agreed was the need for more political engagement from the United States in Afghanistan.

As Roth drolly noted, ‘you can’t kill your way to good governance.’

Roth expressed caution that Afghanistan has only been viewed as a military matter, which he argued has been counterproductive for U.S. objectives in the region, especially with respect to promoting good governance and deepening the rights of women in Afghanistan; he remained hopeful, however, that the troop drawdown would open space in the U.S. agenda for further political engagement.

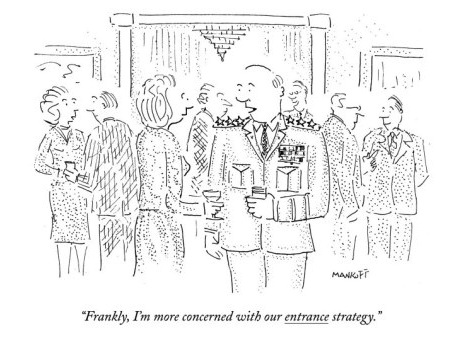

Even Kagan, who strenuously cautioned against an end to the U.S. drawdown in 2014 (which, after all, is two ‘fighting seasons‘ away), noted that the United States needs a political strategy — and he was quick to caution that negotiating with the Taliban is an exit strategy, not a political strategy, and not a particularly smart one at that.

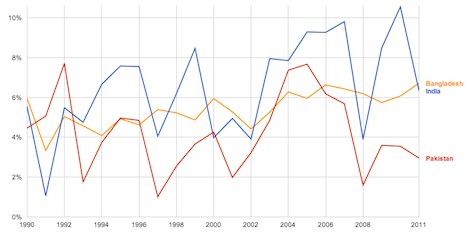

Clemons, who opposes a significant military role in Afghanistan beyond 2014, thoughtfully added, ‘It’s odd we’ve adopted a country that we don’t seem to want to be very close to,’ questioning why U.S. officials haven’t developed closer ties to develop economic opportunities or reduce trade barriers. He noted, too, that the amount the United States spends annually on its military action in Afghanistan (around $198 billion in fiscal years 2012 and 2013, according to this source) dwarfs in multiples the country’s GDP — around $20 billion or so in 2011.

Looking ahead to December 2014

But none of that answers the fundamental question of what we’ll mean in, say, December 2014, when we talk about the ‘Afghan government’ — and that’s a pretty important question. Continue reading Will Hamid Karzai really step down as Afghanistan’s president in August 2014? →

![]()

![]()