CARACAS, Venezuela — Polls closed at 6 p.m. (6:30 p.m. EST) and we have no results yet.

Opposition candidate Henrique Capriles within the past hour tweeted that he was alerting the world that the chavista government is trying to subvert the will of the people.

Opposition leader Leopoldo López followed up with his own tweet warning the government that ‘we know what you know.’

That’s pretty aggressive.

Results weren’t announced in the October 2012 election until around 10 p.m., but an opposition campaign source noted a couple of days ago that the later the result is announced, the better for the opposition.

9:01 pm: Francisco Toro at Caracas Chronicles is reporting that a Capriles campaign quick count shows a very narrow lead for Capriles. That’s certainly more promising than an exit poll.

Meanwhile, at Capriles headquarters, the chairman of the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD, the Democratic Unity Roundtable), Ramón Guillermo Aveledo is very bullish. He says the opposition will wait for CNE (the National Electoral Council) to announce results, but threatens that the opposition will start announcing results if the CNE doesn’t. This is in contrast to a relative angrier and defensive appearance by Jorge Rodríguez, the campaign leader of the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, or United Socialist Party of Venezuela), who spoke earlier to note that turnout was high, and called for calm.

9:16 pm: We’re sort of in new territory now. If Capriles has indeed won, and every indications from Capriles headquarters are that he has, there’s no precedent for a peaceful transfer of power. But after 14 years of chavismo, it’s hard to know what come next. Even if Capriles has lost by a narrow margin, we’re in for a long (and perhaps tense) night. Stay tuned.

9:30 pm: The Capriles campaign has the same votes as the CNE, but winning more votes doesn’t mean that CNE will just stand down, announce Capriles the winner, and thereupon peacefully transfer power. The key arbiter in this scenario would the armed forces, and many of their leaders have a vested interest in a win by chavista candidate Nicolás Maduro. So though the army’s leaders emerged relatively early in the evening to assert their role in protecting the vote, if Capriles has won, don’t expect an announcement, but a lot of behind-the-scenes negotiations between Capriles HQ and Maduro HQ. After 14 years in power, and 14 years spent disrespecting much of the tenets of a liberal democracy, it’s going to be a lot more difficult.

9:35 pm: When I talked to Capriles advisers on Friday morning, they warned that if Capriles does win more votes than Maduro, the most aggressive chavista supporters, gangs of armed partisans, may well incite violence. This is why Capriles has regularly appealed to the military to keep the peace.

When I talked to López, he struck a cautious note as well:

‘We hope that the people will be a buffer to that, the people not only voting, but the people in the streets, people defining their commitment with a new face for Venezuela,’ he said. ‘[The chavistas of course will have the intention of using what they’ve always used — violence, intimidation, abuse of power. But it’s in the hands of the people in the streets to hinder that.’

9:52 pm: We’re approaching the time when October 2012 election results were announced, and there’s not yet any indication that the CNE is about to announce a result in this election. In that election, Chávez defeated Capriles by 10.76%.

9:55 pm: As I wrote on Friday, the difference between Chávez and Capriles six months ago was 1.6 million votes — Capriles won 6.59 million votes and Chávez 8.19 million votes. Assuming the same base in today’s election for Capriles (6.59 million votes), Capriles needed to get either 19.5% of the chavista base to abstain, 9.75% of the chavista base to switch to Capriles from Maduro this time around, or some combination of the two — say, by having 9.75% abstention and a Maduro-to-Capriles swing of 5%. That’s never been incredibly outside the realm of possibility, especially given the late-breaking momentum of Capriles and the defensive campaign that Maduro’s run.

10:05 p: We’re now awaiting the first bulletin from the CNE.

10:10 pm: My source in the Capriles campaign says they won. So all eyes are now on the CNE.

10:17 pm: Pots are banging in the Sabana Grande neighborhood in Caracas. That’s the cacerolazo traditional form of protest from the esquálidos, the opposition supporters — so named because Chávez called them the ‘little squalid ones’ once upon a time. It’s a far cry from the toque de Diana that I heard earlier this morning, the horns blaring a reveille for 13 minutes starting at 3:30 a.m., long a chavista tradition. The change, in 19 hours, from the chavista horns to the caprilista pots banging, is a metaphor for the change in the air today as the opposition has become increasingly optimistic.

10:22 pm: Gunshots are ringing out — a clear sign that the chavistas want to make some noise too.

10:32 pm: It’s worth noting for non-Venezuelan readers that Hugo Chávez didn’t go undefeated in elections over his 14-year rule. He lost a referendum in December 2007 when he pushed to amend the constitution to abolish presidential term limits, curb central bank independence, and allow the president to assert more control over the selection of state governors and mayors. That overreach — and the failure of the chavista electoral machine — showed that Chávez and the PSUV wasn’t invincible.

10:40 pm: While we wait for some further news about what’s happening at the highest levels of Venezuela’s power struggle, it’s worth noting that the MUD is a very diverse group of political parties that have banded together for electoral purposes. If Capriles wins, he’ll not only face a National Assembly that’s still dominated by chavistas and an entire state infrastructure, from the bureaucracy of the government to the courts to Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) dominated by chavistas, but a very wide coalition that includes many parties. The MUD has been more successful than a previous coalition attempt, the Coordinadora Democrática, which disbanded in frustration after Chávez won a referendum to recall him from the presidency by a lopsided 59.1% to 40.6% margin in August 2004.

10:49 pm: One of the issues that Aveledo mentioned earlier tonight was the importance of every vote being counted, especially the votes of Venezuelans abroad. There’s a lot of doubt that those votes will ever fully reach Caracas, and the Miami consulate actively stood in the way of largely anti-Chávez Venezuelan expats, who traveled to New Orleans to vote in both October and again in this election. Reports from the Caracas airport earlier today suggest that only one passport agent was available to allow expats back into the country, obviously back in the country for the purpose of voting.

11:00 pm: It’s been exactly five hours since polls closed across Venezuela, and so far, radio silence from the CNE.

11:14 pm: Here come the rectors at the CNE. Maybe we’ll have an official announcement shortly. At the podium.

11:18 pm: The official announcement from the CNE, with 99.12% of votes counted is 78.71% participation, is 50.66% for Maduro to 49.07% for Capriles. Hard to believe the Capriles campaign is going to accept this, so the long night is about to get even longer.

11:23 pm: Gunshots and music blaring here in Sabana Grande. The official count is 7,503,338 for Maduro and 7,270,403 for Capriles. But no one believes that right now. First question is whether the government is making this announcement with the full support of the armed forces. Second question is whether the opposition MUD will now announce their own set of results — they have access to the same numbers as the government, so it will be interesting to see how long it takes to call their bluff.

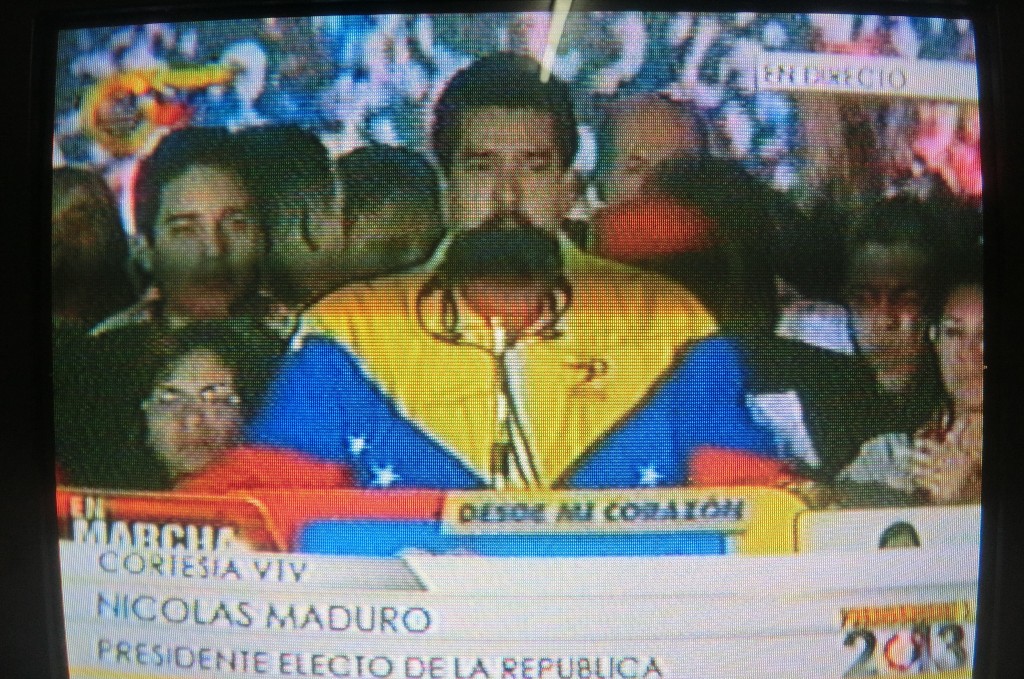

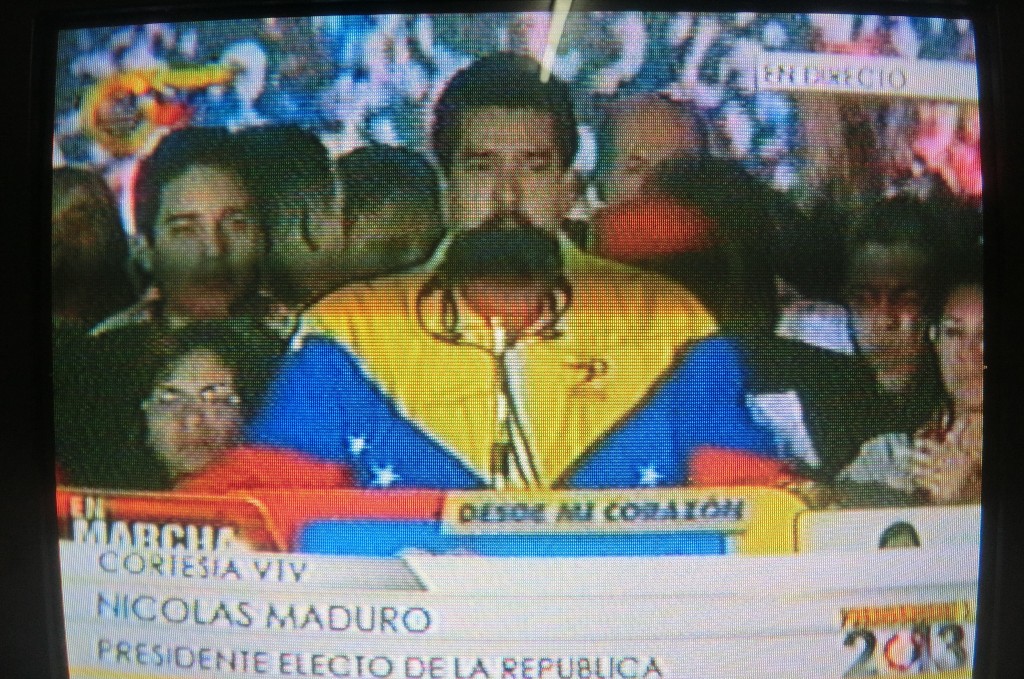

11:24 pm: Maduro is now addressing the crowd (yes, in a tri-color jumpsuit!)

11:26 pm: Capriles will also address the Venezuelan people shortly.

11:35 pm: Maduro is saying that Capriles called and offered a formal pact, but he said no. Caracas is ablaze with the sounds of music and fireworks from Maduro supporters. So it will be interesting to see what Capriles has to say, presumably after Maduro is done with his speech at Miraflores. If this is the actual result, or if it’s fake, it certainly makes Maduro seem like he stole the election. As Francisco Toro writes at Caracas Chronicles tonight, it really is the worst-case scenario.

11:43 pm: The CNE and Maduro will support a full recount and audit of the votes.

11:46 pm: Does anyone know how many times he’s mentioned Chávez tonight? I’ve lost track, but at least a dozen.

11:52 pm: Maduro hasn’t even finished his speech (which I suspect has run so long to prevent Capriles from speaking anytime before midnight), but Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has already congratulated him on his victory.

11:55 pm: Maduro is done speaking, so now the focus will shift to Capriles, who has a difficult task ahead of him. The 64,000-bolívar question is whether he accepts the CNE’s results (even with the audit) or declares his own victory on the basis of his campaign’s own information.

12:02 am: Actually, no, Maduro wasn’t done speaking. Here’s Fidel Castro’s response — simply, ‘Maduro’s won, the revlution continues.’ Not exactly a ringing endorsement.

12:11 am: OK, now he’s done, with a couple of ‘viva Chávez’ and a ‘hasta la victoria siempre.’

12:13 am: For the record, even if the CNE numbers ultimately turn out to be 100% correct, it would represent a drop-off of 680,000 votes from Chávez’s victory six months ago and a gain of 680,000 votes for Capriles. Turnout dropped by just 2%, so that’s around 296,000 votes, if we assume that that dropoff came mostly from the chavista camp. That means that 192,000 chavistas switched to Capriles, or Capriles picked up 384,000 new voters. Either way, it’s a huge victory for the opposition, given where he started a few weeks ago.

12:16 am: Here’s Capriles about to give his speech.

12:19 am: Holding up a stack of voting irregularities, Capriles denies Maduro’s story about a pact, calling him a liar.

12:23 am: Capriles will not concede or accept the result until a full recount has been held of each and every vote.

12:26 am: Says that the MUD has a different result than the one announced, but doesn’t provide the actual result.

12:27 am: ‘My pact is with God and Venezuela.’

12:30 am: Capriles is taking an aggressive tone as ever with Maduro, saying that if he was illegitimate before, he’s still illegitimate and that the results do not reflect the truth in the country. Nonetheless, Capriles is not declaring victory outright — he’s holding back from that step, at least por ahora.

12:39 am: Major general Wilmer Barrientos: “Quiero felicitar al Presidente Electo Nicolás Maduro, usted es el jefe de la Fuerza Armada Nacional Bolivariana.” So that’s where the armed forces stand.

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — Caracas, Venezuela, April 2013.

![]()