It was the worst night for Scottish nationalism in over a decade — worse, perhaps, than the narrow vote against independence in 2014.![]()

![]()

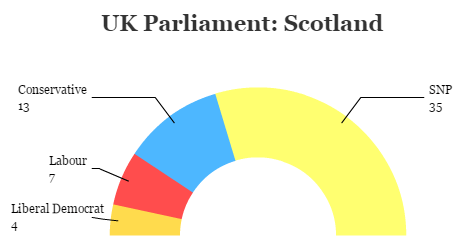

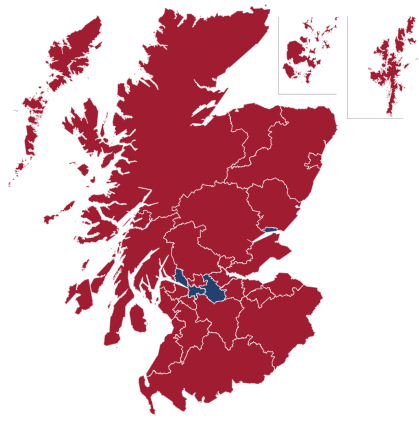

Though the Conservative Party lost its majority at the national level, thanks to a loss of 21 seats in England, it will stagger on as the largest party in the House of Commons thanks in no small part to a surge in support in Scotland, where the party picked up 13 seats, all at the expense of the pro-independence Scottish National Party.

Though the SNP still won a greater share of the vote and more seats than any other party in Scotland, it was a very bad night for the party, which lost more seats, in total, than the Conservatives nation-wide. It was the worst electoral performance for the SNP since 2010 — former SNP leader Alex Salmond lost his seat in Gordon, and deputy SNP leader Angus Robertson lost his seat in Moray. Other MPs, like Mhairi Black, the 22-year-old who is the youngest member of the House of Commons, were easily reelected.

Though the SNP still won a greater share of the vote and more seats than any other party in Scotland, it was a very bad night for the party, which lost more seats, in total, than the Conservatives nation-wide. It was the worst electoral performance for the SNP since 2010 — former SNP leader Alex Salmond lost his seat in Gordon, and deputy SNP leader Angus Robertson lost his seat in Moray. Other MPs, like Mhairi Black, the 22-year-old who is the youngest member of the House of Commons, were easily reelected.

It was a sign, perhaps, that Scottish voters are growing weary of the SNP’s focus on independence after first minister Nicola Sturgeon’s pledge to demand a second referendum on Scotland’s status after Brexit negotiations conclude in 2019. As all three national parties made gains in yesterday’s general election (including what amounts to one-third of the Liberal Democratic caucus in the House of Commons), it leaves Sturgeon and the SNP in a precarious position.

After becoming the indisputable leftist opposition to conservatism in Scotland, the SNP now faces the dual threat of a plausible Tory unionism to its right and a resurgent Labour under an equally left-wing Jeremy Corbyn.

Though Sturgeon won a fresh mandate in the Scottish parliamentary election last May (and will not face voters again until 2021), the SNP’s plurality in the Scottish parliament in Edinburgh falls two seats short of an absolute majority. While the SNP and its allies currently command a majority in favor of calling a second referendum, the 2017 general election result may force Sturgeon to rethink that approach in favor of more quotidian concerns. Moreover, she will have to reorient the SNP approach after it has held power in Scotland since 2007, first under Salmond and, since 2014, Sturgeon. Not an easy task for a party that thought it could keep amassing outsized margins solely by demanding a second referendum.

Sturgeon herself admitted that the ‘referendum-or-bust’ approach may have backfired. Since prime minister Theresa May triggered Article 50 in March, Sturgeon and the Scottish government have demanded a second referendum on independence for Scotland. The region’s voters narrowly chose in September 2014 to stay in the United Kingdom by a margin of 55.3% to 44.7%. The same voters, however, opposed Brexit in the June 2016 EU referendum by a margin of 62% to 38%, joining ‘Remain’ majorities in Northern Ireland and London.

Sturgeon has threatened that if the Brexit negotiations do not leave Scotland with access to the European single market (and a ‘hard’ Brexit would not guarantee that access), Scottish voters deserve the chance to seek independence again as one way to return to the European Union.

Continue reading In Scotland, the unionists (and Ruth Davidson) strike back