There’s no doubt that the landmark vote in Ireland on May 22, the first such referendum where a popular majority enacted same-sex marriage, has been received as a huge step forward for marriage equality and LGBT rights in Europe.![]()

![]()

While the United States supreme court is set to rule later in June on marriage equality as a legal and constitutional matter within all 50 states, it may feel like a watershed moment in Europe as well, where French president François Hollande and the center-left Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) and British prime minister David Cameron and the Conservative Party both swung behind legislative efforts to enact same-sex marriage, in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Luxembourg’s prime minister Xavier Bettel officially married his own partner in May, but it was only six years ago that Iceland’s Jóhanna Sigurdardóttir became the world’s first openly LGBT head of government, followed shortly by Belgian prime minister Elio Di Rupo.

Yet the lopsided Irish referendum victory — it passed with 62.07% of the vote and the ‘Yes’ camp won all but one constituency (Roscommon-South Leitrim) — obscures the fact that additional marriage equality gains across the European Union will be slow to materialize. Leave aside the notion, now reinforced by Ireland, that the human rights of a minority can be legitimately subjected to referendum — a precedent that Europeans may come to regret. Amid the recent burst of marriage equality in Europe, the immediate future seems grim.

Nowhere is that more true than just next door in Northern Ireland, which is the only part of the United Kingdom that doesn’t permit same-sex marriage. With the Protestant, federalist electorate dominated by the socially conservative Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), one of western Europe’s most harshly anti-LGBT political parties, there’s little hope that Northern Ireland will follow in the footsteps of England, Scotland and Wales. At the end of April, Northern Irish health minister Jim Wells was forced to resign after suggesting same-sex couples were inferior parents. It’s home to the late Ian Paisley’s ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy’ campaign in the late 1970s, and it’s where sexual relations between two consenting same-sex partners were illegal until 1981, when the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Northern Irish law violated the European Convention on Human Rights.

But Northern Ireland is not alone in its reticence — marriage equality faces long hurdles in some of the European Union’s most important countries, including Germany, Italy and Poland.

The irony is that despite Europe’s leading role two decades ago on LGBT marriage rights, the United States could eclipse Europe with the supreme court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, as the European Union struggles for years to enact consistent marriage equality legislation.

Germany, today the engine of Europe, the continent’s largest economy and its most populous country, has not enacted same-sex marriage as law. What’s more, chancellor Angela Merkel reiterated in the aftermath of the Irish vote that it’s simply not a priority of the current government, a grand coalition between Merkel’s center-right Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party) and the opposition center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party).

Officially, Merkel’s ambivalence has much to do with social conservatism within the CDU and within its sister party in Catholic-dominated Bavaria, though that didn’t stop Merkel from joining forces for four years with Guido Westerwelle, the openly gay former foreign minister and leader of the CDU’s one-time junior partners, the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party).

The center-left SPD, which includes justice minister Heiko Maas, hasn’t exactly rushed to push the issue. With the support of smaller leftist parties and a handful of socially liberal CDU voters, LGBT activists would have a good shot at winning a victory, even if it would scramble the current coalition dynamics in the German parliament.

Germany’s constitutional court has mandated a kind of civil partnership over the course of a series of rulings, but full marriage equality doesn’t seem likely any time before the next federal election, expected in 2017, nor does it seem likely so long as Merkel is the dominant force in German politics.

If prospects look bleak in Germany, they are downright dismal in Italy, where prime minister Matteo Renzi’s political capital barely seems strong enough to implement even a shadow of the economic and government reforms the former Florence mayor believes will unlock Italy’s economy from the malaise that’s led to three recessions since 2008. As in Germany, there’s little chance for legislative action until after the next election, likely in 2018. Unlike Germany, Italy doesn’t even have a basic civil partnership regime. When Rome’s mayor Ignazio Marino attempted to recognize same-sex marriages from other countries last October, the Italian government quickly stepped in to oppose the action. Nevertheless, as in the rest of Europe, attitudes are quickly changing — in southern Italy, both Sicily’s regional president Rosario Crocetta and Puglia’s outgoing regional president, Nichi Vendola, are openly gay.

As Renzi tries to position the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party) as the 21st century party of natural government in Italy, the last thing he wants to do is start a conflict with Catholic conservatives and the Vatican. After all, it was a fight over registered same-sex partnerships that brought down the center-left government of prime minister Romano Prodi in 2008. Without the support of the center-right Forza Italia, led by former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, himself known for making homophobic comments, it’s impossible to think that Renzi would deploy any major effort to bring same-sex marriages to Rome’s churches.

The climate is particularly hostile in eastern Europe and the Balkans. Shortly after Croatia formally joined the European Union in 2013, it held a referendum later that year, the result of which was a constitutional amendment banning the recognition of same-sex marriage. The current government introduced in 2014 an alternative measure providing life partnerships for same-sex couples.

Poland, like Italy, doesn’t even feature a same-sex partnership alternative. A 2013 Centrum poll showed that while 68% of Polish voters opposed same-sex marriage, fully 60% opposed even registered civil unions or partnerships. Nearly 90% opposed adoption rights for same-sex couples. Attitudes throughout the rest of central and eastern Europe, including Ukraine, are similarly dismal.

For example, when Warsaw held the annual EuroPride festival in 2010 (pictured above), it wasn’t uncommon to see virulently anti-gay activists responding in protest.

Furthermore, encouraging a more liberal view on LGBT rights in central and eastern Europe doesn’t seem like a top priority for the European Union today. In light of fiercely anti-LGBT attitudes espoused in Russian government and culture, it’s not a point upon which EU leaders are keen on raising when there are other pertinent divides in the growing battle to limit Russian encroachment on former Soviet republics and satellites.

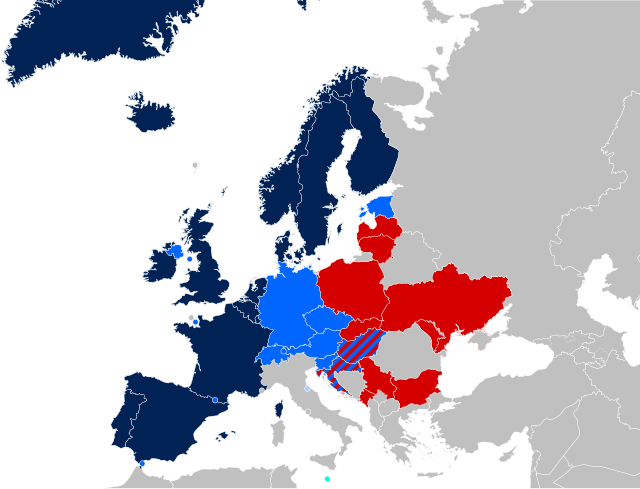

The Netherlands was the first to recognize same-sex marriage (marked in dark blue below) in 2001, followed in short order by Belgium in 2003, Spain in 2005, Norway and Sweden in 2009 and Portugal and Iceland in 2010. Denmark followed in 2012, France in 2013, the United Kingdom and Malta in 2014, Luxembourg in 2015 and Finland’s law will go into effect in early 2017.

A handful of additional states have introduced alternative arrangements (marked in light blue above) — in addition to Croatia’s 2014 law creating ‘life partnerships,’ Slovenia introduced registered partnerships in 2006, as did Switzerland in 2007, Austria in 2010 and Hungary in 2009 (though its constitution also defines marriage as one man and one woman). A new Estonian ‘cohabitation agreement’ regime will take effect in January 2016.

Plenty of EU nation-states, however, have failed to introduce any regime (marked in gray above) or actively define marriage, as a constitutional matter, as one man and one woman (marked in red above).