Everyone expected that if Australia’s ruling Liberal Party were to lose the upcoming by-election in the Canning district, prime minister Tony Abbott would face an uprising against his hard-edged conservative style, even as rumors swirled that Abbott was preparing to call a special ‘double dissolution’ snap election that would involve members of both houses of Australia’s parliament.![]()

No one expected that Abbott would face a leadership ‘spill’ even before the by-election, though it was abjectly clear that Abbott’s premiership was in danger as far back as February, when he defeated a leadership challenge by a vote of just 66 to 39.

Blindsided by a Liberal caucus worried about its fate in Australia’s coming election, which must be held on or before January 2017, Abbott’s internal party critics finally brought him down late Monday night, Canberra time, narrowly electing former leader and communications minister Malcolm Turnbull (pictured above) as the Liberal Party’s new leader — and, therefore, the leader of Australia’s Liberal/National Coalition government and Australia’s 29th prime minister.

Literally overnight, it brings a new government to Australia from the moderate wing of the Liberal Party — a new centrist prime minister who is LGBT-friendly, more likely to balance liberty and security, sympathetic to the fight against climate change and, above all, ready to signal a singular focus on Australia’s growing economic woes.

Turnbull — a moderate and a ‘small-l’ liberal

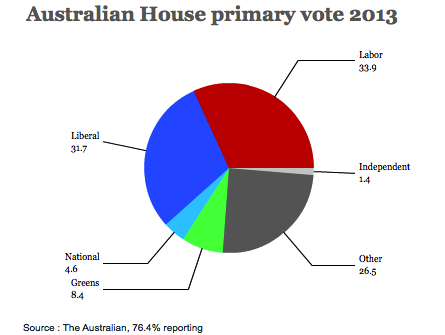

Turnbull is a moderate who has always been much more widely popular with the Australian public than Abbott, whose own prickly personality and economic and social conservatism dragged the current Coalition government firmly to the right. Six months into Abbott’s tenure as prime minister, Australia’s center-left Labor Party, under the new leadership of Bill Shorten, took the lead in polling surveys and never looked back. Labor now holds a healthy lead of between five and 10 points in most surveys on the two-party preferred vote (the measure when all third-party votes are distributed, through second preferences, to Labor and the Coalition, as the two largest parties).

Turnbull’s election will pull the governing Liberal Party back to the center of Australian politics after a two-year Abbott government that’s arguably one of the country’s most right-wing in history.

Turnbull is set to embrace a more urgent tone on economic policy, including a full-throated embrace of the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) signed in July 2015 and the multi-continental Trans-Pacific Partnership. Turnbull, in his post-election press conference, praised New Zealand’s prime minister John Key for enacting economic reforms and explaining them well to the electorate. Joe Hockey, the government’s treasurer (essentially the equivalent of finance minister), an Abbott loyalist who denounced Turnbull’s leadership challenge, seems certain to lose his role as the chief economic policymaker.

Turnbull also embraces a much more liberal view on civil liberties, even in an era of rising national security. Unlike Abbott, who firmly opposes LGBT marriage, Turnbull fully supports it and it’s reasonable to expect that he will allow the Australian parliament to hold a ‘free vote’ on the matter — if for no other reason than to lower tensions on the issue before the next election.

As a former environmental minister who once supported the opposition Labor Party’s attempt to introduce a carbon pricing scheme, Turnbull’s election will give Australia a much stronger voice as November’s global climate summit in Paris approaches.

* * * * *

RELATED: History shows Abbott faces long odds in holding Oz premiership

RELATED: Revoking mining tax, Abbott dismantles Labor achievements

* * * * *

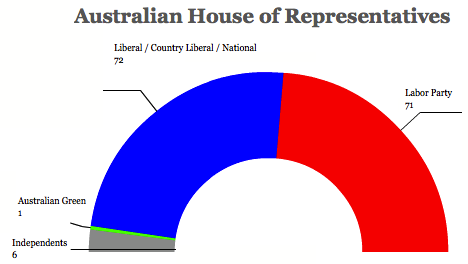

The Canning by-election, scheduled for September 19, comes after the death of Don Randall, a sitting MP who was first elected to the Australian House of Representatives in 1996. The contest, which takes place in a district on the outskirts of Perth in Western Australia, is essentially too close to call, even though Randall and the Liberals easily won the seat in the 2013 election with 51% of the vote (and with 62% of the ‘two-party preferred’ vote).

Though the Coalition’s political troubles are in large part due to Abbott’s personal unpopularity, Turnbull’s election will not magically transform the perilous fundamentals for Liberal reelection hopes. The tanking price of commodities has hurt Australia’s mining-heavy economy, especially as China’s economy stalls after decades of double-digit GDP growth. If Turnbull waits until early 2017 to call fresh elections, Australia might well be in recession. Moreover, Turnbull may seek a personal mandate as the new Liberal leader — in 2010, Gillard called an election almost immediately after succeeding Rudd to legitimize her own premiership.

It’s difficult to say what the Turnbull coup will mean for Saturday’s by-election. The new prime minister may himself call snap elections earlier than absolutely necessary, despite the fact that the current government can expect to command a stable majority for the next 16 months.

Second time lucky

A Sydney native, Turnbull is a banker whose first involvement in Australian politics came in 1993, when he chaired the Australian Republican Movement, which aims to make Australia a republic with an elected president (and not a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state) — republicans only narrowly lost a 1999 referendum on creating such a republic. Though the 1999 fight brought together traditional allies from the right and the left, Abbott is a committed monarchist and he drew derision in January when he awarded a knighthood to prince Philip, Queen Elizabeth II’s husband.

Elected to the Australian parliament in 2004, Turnbull’s ascent was rapid and, in the final year of prime minister John Howard’s government, Turnbull served as minister for the environment and water. Though he won the Liberal leadership in 2008, discontent among the opposition’s right flank to the Labor carbon pricing scheme forced him out nearly a year later after Turnbull instructed his caucus to support the bill. After two leadership spills in a week, Abbott usurped the leadership in December 2009 after two ballots, by the narrowest margin of 42 to 41.

Photo credit to Mike Bowers / The Guardian.

Photo credit to Mike Bowers / The Guardian.

The rest is history.

Abbott led the Liberals to a narrow defeat in the 2010 election, but he held onto the premiership long enough to win the 2013 election. Bringing the climate change policy showdown full circle, Abbott (pictured above after his Monday night defeat) and a handful of third-party allies successfully revoked the carbon trading scheme in July 2014. Continue reading Turnbull ousts Abbott as Australia’s new prime minister