Georgians went to the polls today to elect members to the 150-member Georgia parliament today.

Both of the main contenders — the United National Movement (Ertiani Natsionaluri Modzraoba, ერთიანი ნაციონალური მოძრაობა) of president Mikheil Saakashvili and the Georgian Dream — Democratic Georgia party (k’art’uli ots’neba–demokratiuli sak’art’velo, ქართული ოცნება–დემოკრატიული საქართველო) of Georgia’s wealthiest man, Bidzina Ivanishvili, have claimed victory in the race.

Exit polls show Georgian Dream and the United National Movement either tied or with Georgian Dream narrowly ahead. A little over half (77) of the 150 seats are determined by proportional representation and the rest (73) are determined by single-majority constituencies across Georgia. Although Georgia Dream may lead among the 75 seats allocated by party list, it is believed that Saakashvili’s United National Movement has a significant edge among the individual first-past-the-post constituencies.

The race pits two very strong-minded personalities against one another — and two very different narratives of the past eight years since Saakashvili took power following the so-called ‘Rose Revolution’ — a series of protests that ushered Eduard Shevardnadze out of office after 12 years in power since the fall of the Soviet Union and ushered in a new wave of leadership under Saakashvili and his free-market, technocratic, pro-Western followers.

The election has taken on increased urgency due to constitutional reforms, which transfer much of the institutional power from the office of the president to the prime minister when Saakashvili — or ‘Misha,’ his nickname — completes his presidential term next year. While it is too early to know if Saakashvili will run for reelection, if his party loses control of Georgia’s parliament this year, much of his current powers will flow to Ivanishvili’s coalition by next year.

Given Ivanishvili’s resources, however, the race has also been the most competitive since Saakashvili was elected president in 2004, and Ivanishvili has zeroed in on the failures and excesses of the Saakashvili era (of which there have been many).

Saakashvili (pictured above, top) and his supporters can point to a country that has developed a more dynamic economy — whereas corruption was so bad at the end of the Shevardnadze era that Tbilisi only had intermittent electricity, the Georgian economy at around 6% in 2010 and nearer to 7% in 2011. If Saakashvili can boast a Georgia with less crime and corruption and a much more functional and thriving economy, he can also point to clear, if imperfect, trends toward greater rule of law and democratic norms. Today’s election — and the credible chance of an opposition win, or significant gains, is a testament to progress. If Saakashvili loses today’s election, a peaceful transfer of power to the opposition would likewise mark one of the highest points of his eight years in office — the protests that saw Shevardnadze fall began after the fraudulent result of the November 2003 parliamentary elections.

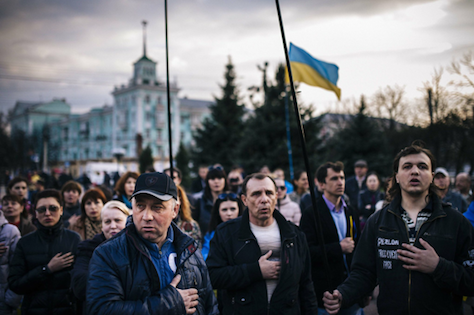

Ivanishvili (pictured above, bottom) and the opposition, however, point to a government that treats its political opponents like enemies and that routinely exceeds the boundaries of Western norms for the rule of law and human rights. At the top of the list of long-standing concerns in Georgia are media freedom and the abuse of government, taxation and regulation power to harass opposition figures. Most recently, in the final two weeks of the campaign, damaging video aired on anti-Saakashvili television channels implicated the government in a prison scandal whereby inmates have been mistreated, beaten, raped and tortured. Although the timing of the revelations is suspicious, the extent of the abuse is unclear, and it’s unknown whether the abuse was more isolated or a systemic, organized effort within the Georgian prison system, the ‘Georgia Abu Ghraib’ has clearly turned the tide against Saakashvili in the final days of the election, notwithstanding the resignation of the interior minister, Bacho Akhalaia.

Ivanishvili, too, has attacked Saakashvili for the 2008 war with Russia that left the breakaway republics of South Ossetia and Abkhazia under Russian military control. He’s probably right — Saakashvili’s provocations gave Moscow exactly the reason it needed to justify an occupation that it had hoped to make for years. Saakashvili mistakenly hoped that NATO and other Western forces would come to his rescue, a miscalculation that has led to the continued Russian occupation in the two provinces even today (neither South Ossetia nor Abkhazia voted in today’s election).

Saakashvili has angered the administration of Russian president Vladimir Putin for his bids to join both the European Union and NATO. Both are a bit of a stretch, given that Tbilisi lies over 2,400 miles away from Brussels — and even 1,100 miles away from Athens, which itself rests at the periphery of the European continent. But Saakashvili’s enthusiasm for the West remains strong, and the EU and the United States has reciprocated that interest, given Georgia’s progress on economic and other reforms and its pivotal role in transporting natural gas from Russia to Europe. Georgia, a small nation of just 4.5 million people, would comprise much of a proposed ‘trans-Caspian’ pipeline that would link Azerbaijan, on the Caspian Sea, to Turkey, on the Black Sea.

Ivanishvili has promised better relations with Russia (while not necessarily painting himself as anti-Western), and argued that he can work with Russia to end the embargo that Russia has placed on Georgian agricultural products, wine, mineral water and other goods since 2006.

Saakashvili has painted Ivanishvili as a shadowy businessman, who in fact made his $6.4 billion fortune in Russia — like many oligarchs, by buying cheap, formerly state-owned assets following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Before last October, Ivanishvili was a bit of a recluse in Georgia, despite ample amounts of charitable giving to Georgians throughout the country. Saakashvili has also attacked the motley nature of Ivanishvili’s coalition, which is united over little beyond opposition to Saakashvili, and which has attracted everything from free-market liberals to religious fundamentalists and xenophobic elements.

Going into today’s election, the United National Movement controlled 119 seats, almost 80% of Georgia’s parliament. Georgian Dream controls no seats (it’s the first election campaign for Ivanishvili’s group), various opposition control 17 seats, and two small parties, the center-right Christian-Democratic Movement and the center-left Georgian Labour Party, control six seats each.

![]()

![]()