India starts its massive, nearly five-week, nine-phase general election in just seven days.![]()

![]()

So you figure that US-Indian relations must be on fairly poor terms when the United States ambassador to India, Nancy Powell, stepped down on Monday after less than two years on the job.

According to reports in both the United States and India, Powell had become increasingly ineffectual due to the Khobragade affair.

* * * * *

RELATED — In Depth: India’s elections

* * * * *

Her resignation came amid growing reports that her recall was imminent, though US officials strongly denied that yesterday:

And at a Monday briefing, deputy State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf strongly denied that Powell’s resignation was anything but a 37-year career diplomat retiring after serving posts all over the world….. “All the rumors and speculation are, quite frankly, totally false,” Harf said.

Powell’s decision wasn’t really Powell’s fault — she will retire in May after a 37-year career in the foreign service, having served as the US ambassador to Uganda, Ghana, Pakistan and Nepal, as an assistant acting secretary of state three times, director general of the US Foreign Service, and previously as consul general in Kolkata (previously Calcutta) in the early 1990s and political counselor at the US embassy in India in the mid-1990s.

So Powell was already one of the most experienced hands that the US state department could have deployed to India.

The Khobragade incident is essentially a minor diplomacy scandal. US officials arrested deputy consul general Devyani Khobragade in December of last year on suspicion of visa fraud — and then strip-searched and detained Khobragade. The incident initially caused a minor kerfuffle over diplomatic privileges and immunities, but quickly escalated to the point where it’s had an extremely adverse effect on the bilateral relationship. India began stripping US diplomats of certain privileges, and Indian officials made themselves increasingly less accessible to Powell.

Meanwhile, Powell had to deal with the even thornier issue of how the United States ought to handle Narendra Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat and, increasingly the frontrunner to become India’s next prime minister. Modi, who’s leading the parliamentary election campaign of the center-right, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) was denied travel visas to both the United Kingdom and to the United States, the latter in 2005, stemming from the controversy over Modi’s role in fomenting — or at least, not stopping — the worst Hindu-Muslim riots of the past two decades in 2002, which left over 1,000 Muslims dead and occurred shortly after Modi took office in Gujarat.

Following the release of a recent report from the US Congress, that policy seems almost certain to change if Modi becomes India’s next prime minister.

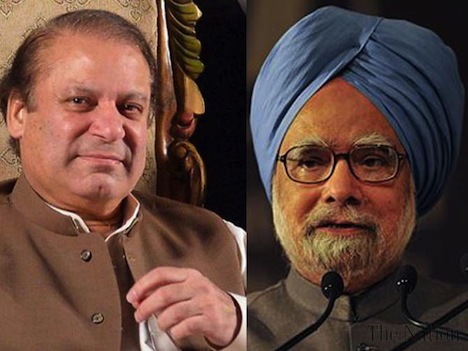

Powell met Modi in February, the first ambassador to do so since Modi emerged as a potential prime minister. But the Khobragade affair delayed the meeting (pictured above), and some reports from India claim that Washington faults Powell for being too close to the administration of Mamohan Singh and foreign policy advisers within Singh’s party, the Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस).

Modi hasn’t spoken at length about his foreign policy, but most Indian observers believe he will be relatively more muscular vis-à-vis Pakistan, relatively more aloof with Europe and the United States, and relatively friendlier with China, on the basis of past trade-related cooperation between China and Gujarat.

With a fresh start, expect US president Barack Obama to appoint a relatively high-profile political ambassador to replace Powell. One option he should consider is Bobby Jindal (pictured above), a two-term governor of Louisiana, former member of the US House of Representatives, a conservative Republican and an Indian American who was raised in a Hindu household, though he later converted to Roman Catholicism.

It wouldn’t be the first time that Obama recruited a sitting Republican governor for such an important post — Utah governor Jon Huntsman served as the Obama administration’s ambassador to China from 2009 to 2011.

Though the India portfolio isn’t always filled by a high-profile political official, there’s a long pedigree of important figures in the role: Continue reading US ambassador to India resigns a week before Indian elections