Yesterday, the new government of Delhi’s national capital territory launched a new anti-graft hotline that received nearly 4,000 calls on its first day.![]()

In what was supposed to be the year of Narendra Modi’s easy rise to India’s premiership, it’s another brash new leader who’s making headlines instead — and not just in India, but worldwide.

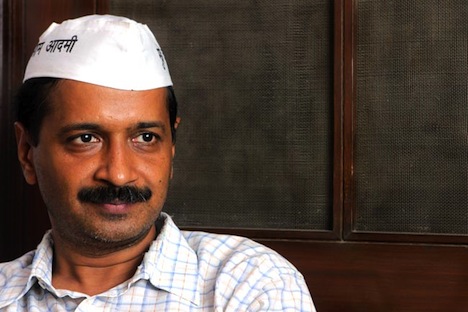

It’s Arvind Kejriwal, the leader of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी), literally the ‘Common Man’ Party, which emerged as the key player in Delhi’s December regional elections as an alternative to Modi’s conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) and the governing center-left Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) of Sonia Gandhi, the party’s leader; Rahul Gandhi, her son; and outgoing prime minister Manmohan Singh.

Kejriwal, at age 45 one of India’s youngest chief ministers, took office on December 28, leading a minority government that, somewhat ironically, enjoys the outside support of the INC, which controlled Delhi’s government between 1998 and last December’s elections. Congress, which was running for a fourth consecutive term in power under chief minister Sheila Dikshit, was decimated — it not only lost its majority, but now holds just eight seats, after suffering from widespread corruption allegations. Kejriwal actually ran in Dikshit’s New Delhi constituency and defeated her by a margin of 53.5% to 22.2% (state BJP leader Vijender Gupta received just 21.7%).

Though the BJP actually won the greatest number of seats (31 to the AAP’s 28), negotiations between the AAP and the BJP failed, and Kejriwal took up Congress’s somewhat surprising offer to back his government, thereby avoiding a new round of elections. Unlike other regional parties in India, the AAP managed to take power on a broad coalition of supporters, not on the basis of representing certain religious or class-based constituencies — it attracted Muslims and Hindus, rich and poor, Dalit and non-Dalit, and especially India’s educated younger generation.

Kejriwal, a mechanical engineer by training and a former Indian Revenue Service official, started an NGO in 1999 called Parivartan, designed to provide tax assistance and other help to Delhi citizens. But it was as an anti-corruption official that Kejriwal first caught fire in the national spotlight, and under the mentorship of Anna Hazare, worked to demand what would eventually become the Right to Information Act (RTI) in 2005, which required government bodies to reply to citizen requests for information within 30 days or face penalties, and which relaxes many previous exemptions from disclosure under the Official Secrets Act and other legislation. RTI replaced the much weaker, toothless and exemption-ridden 2002 Freedom of Information Act.

In 2011, Anna and Kejriwal succeeded in pushing the government to start the process for drafting a Jan Lokpal bill, an anti-corruption law that would create the Jan Lokpal, an independent citizen’s ombudsman commission that would have the ability to investigate corruption. Though India’s parliament pushed through a Lokpal Bill in December 2013, it’s much weaker than the proposed Jan Lokpal Bill — for example, it doesn’t protect whistleblowers, it doesn’t provide for any real punitive actions or the ability to prosecute corrupt bureaucrats, and it doesn’t provide investigative independence to India’s Central Bureau of Investigation. Kejriwal took the final leap into elective politics when he founded the AAP in November 2012 with the intention of contesting Delhi’s local elections.

Having now swept to power in Delhi (literally on the image of a broom ‘sweeping’ corruption away), Kejriwal wasted no time in announcing a 50% cut in power rates and free water to Delhi residents within hours of taking power. He’s already working to implement the AAP’s anti-corruption agenda with the anti-graft hotline, and he’s pledged to introduce a Jan Lokpal bill specifically for Delhi soon.

There’s good reason for Kejriwal to be in a hurry — with the AAP’s momentum spreading from Delhi to other parts of India, it could be in a position to make a splash in national politics with the upcoming elections for the Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the lower house of India’s parliament, which are due before May 31. That gives Kejriwal some time to lay the foundation for what the AAP might be able to accomplish on a grander scale, a down payment on what a national anti-corruption party could enact.

After a decade of rule under Singh’s Congress-led governments, Indian voters are weary with Congress . Its prime minister-in-waiting Rahul Gandhi seems unexciting and disinterested. Indians are displeased with Congress’s reform record and the state of India’s precarious economy. Meanwhile, the AAP has highlighted a growing disenchantment over bureaucratic corruption.

Though Modi, the decade-long chief minister of Gujarat state, promises to lead a BJP government that will bring Gujarat’s high economic growth rates to the entire country, there are doubts both about the extent to which Modi’s ‘Gujarati model’ is responsible for his state’s growth and how (and whether) such a ‘Gujarati model’ could even be translated to a much more diverse national economy. Moreover, the 2002 anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat continue to blemish Modi’s record. Though he recently spoke out for the first time disclaiming any role in the violence, the riots, which resulted in the death of over 1,000 Muslims, will continue to haunt Modi’s campaign and the notion that he can be a trustworthy prime minister for India’s religious minorities.

So what damage might Kejriwal inflict on the status quo? Plenty.

For starters, Congress currently holds all seven of Delhi’s seats to the Lok Sabha, and it’s hard to believe that the AAP won’t make a go at all of them. In surrounding Haryana, Kejriwal’s native state, the AAP will also have a strong shot at its 10 Lok Sabha seats, nine of which are currently held by Congress. But as the AAP prepares to unveil a national campaign, it promises to make a far deeper impact.

A January IPSOS poll conducted in India’s eight most populous cities shows that 44% of voters would support the AAP today, and another 27% are open to voting for the AAP if it fields a strong local candidate. While 58% of urban voters prefer Modi as prime minister, 25% prefer Kejriwal and just 14% prefer Rahul Gandhi.

Kejriwal has ruled out running himself in the Lok Sabha elections for the time being, but the AAP seems to be charging full-speed ahead with spring elections, and it hopes to enroll 10 million (1 crore) members by the end of the month. There’s a good chance that Kejriwal and the AAP are already changing the campaign agenda from a focus on the economy to a dual focus on the economy and corruption. The two issues aren’t unrelated — graft costs India billions of dollars every year. Though both Singh and Modi have reputations as public servants of the highest integrity, both the BJP and Congress are weak on the issue.

Congress is especially vulnerable to attacks on its anti-corruption record. Nothing encapsulates the culture of corruption more than the 2G spectrum scandal of the late 2000s, through which government officials undercharged favored mobile telephone companies for frequency allocation licenses — India’s supreme court in 2012 eventually nullified all of the licenses. Singh’s choice to lead the Central Vigilance Commission (India’s top anti-corruption body), PJ Thomas, was forced to step down after six months on the job in March 2011 after he himself was implicated in an oil import scam. Another scandal in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest, in which officials were caught siphoning over $1.5 billion from the National Rural Health Mission program to provide health care and other support to the poor led to the defeat of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP, बहुजन समाज पार्टी) in the February 2012 regional elections.

It’s no surprise, then, that the AAP has already decided to compete for all 80 of Uttar Pradesh’s seats in the Lok Sabha, where Congress’s 21 seats and the BSP’s 20 seats are in jeopardy. It sets up a five-way fight among the AAP, the BSP (with a strong base among the state’s Dalit population), Congress, the BJP and the Samajwadi Party (समाजवादी पार्टी, Socialist Party), which draws many Muslim supporters, currently holds 23 seats and controls the state’s legislative assembly. Though the Samajwadi Party and the BSP have essentially dominated local politics in Uttar Pradesh for the past two decades, they have poorer records on corruption, if anything, than the INC and BJP.

Congress’s ineffectiveness on corruption feeds into a broader narrative on its — and Singh’s — other failures. Two decades after Singh’s landmark economic reforms as finance minister, Singh has failed to follow up as prime minister with reforms that would permanently end the ‘license raj’ era by consolidating India’s confusing and sluggish bureaucracy. Despite an eleventh-hour set of retail sector reforms last year, Singh hasn’t been able to change India’s restrictive foreign investment laws or its confusing labor market laws.

Kejriwal’s rise will also force Modi and the BJP to shift strategies. With the AAP as a legitimate contender, no longer will Modi be able to depend solely upon antipathy against Congress to ride to power. Modi will instead be forced to compete with the AAP for anti-Congress votes, especially among those middle-of-the-road voters who delivered victories to the INC in 2004 and 2009 but who find themselves rather disenchanted in 2014. That means Modi will need to deliver specific measures designed to address corruption in a more fulsome manner than he’s done so far, not to mention do much more to reassure minority voters.

The most ambitious template for Kejriwal might be the 1977 Indian election, which brought the country its first non-Congress government. The Janata Alliance, which was hastily cobbled together to oppose Indira Gandhi’s Emergency declaration in 1975, won 298 seats by opposing Gandhi’s grab of near-dictatorial powers of the government, security forces and the media, ostensibly in relation to the country’s recent war with Pakistan. Janata’s success in 1977 proves that a new alliance can emerge on short notice to win national power in India — and that should be even more true in the era of social media. (Of course, by 1980, Indira Gandhi returned to power and the Janata Alliance had split into many different pieces, the largest of which is the forerunner to today’s BJP).

But the road won’t necessarily be free of obstacles for the AAP. It has virtually none of the national or state-level electoral networks that Congress and the BJP have developed for decades. As Kejriwal and the AAP pose a sharper challenge, both the BJP and Congress are likely to turn their fire on the AAP. The BJP is already taunting Kejriwal for not prioritizing corruption investigations of former Congress officials in Delhi, given that Congress is currently floating Kejriwal’s minority government.

Even if the AAP manages to place well among urban constituencies, India has a larger rural population, by far, so India’s urban population amounts to just 31% of total population. In Uttar Pradesh, just 22% of its 199 million residents live in urban areas. The AAP is also anticipated to be relatively weaker in India’s south.

Thanks for a marvelous posting! I genuinely

enjoyed reading it, you could be a great author.I will be sure tto bookmark your blog and will eventually come back at

some point. I want to encourage one to continue your great work, have a nice hholiday weekend!

My web site … Las Vegas Refrigerator Repair