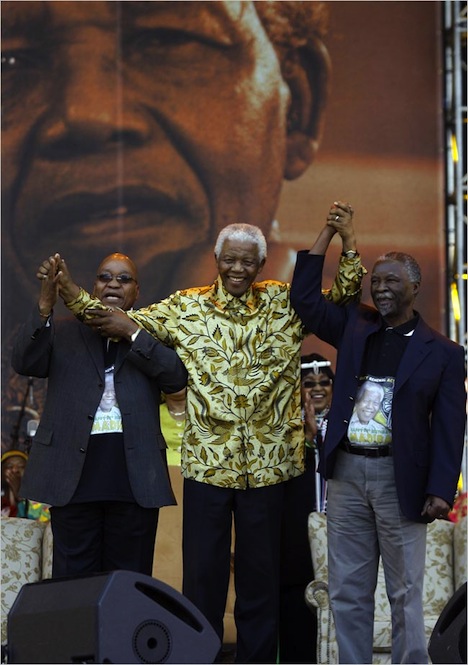

No one could have filled the shoes of Nelson Mandela, the first president of post-apartheid South Africa — not that either of his successors in recent years tried particularly hard to do so. ![]()

Thabo Mbeki (pictured above, right, with Mandela), who served as Mandela’s competent executive during Mandela’s term as South African president between 1994 and 1999, became known during his own decade in office as the world leader who refused to admit the connection between HIV and AIDS long after the scientific community established that the human immunodeficiency virus is the proximate cause of AIDS.

Jacob Zuma (pictured above, left, with Mandela), who followed Mbeki into the presidency after the 2009 general election, came to power virtually synonymous with illegality after surviving criminal charges for rape and for corruption in the mid-2000s. Mbeki himself was forced to resign in September 2008 as president because of allegations that he interfered in the judicial process on behalf of Zuma.

With a general election due in spring 2014, however, Mandela’s death presents both an opportunity and a challenge to South African politics. Mandela’s absence means that the space is once again open for a South African leader to inspire the entire nation without facing the inevitable comparison to one of the world’s most beloved figures. But it also marks the end of post-apartheid South Africa’s honeymoon, and so Mandela’s passing also represents a challenge to the new generation of political leadership — to dare to bring the same level of audacious change to South Africa that Mandela did. Nothing less will be required of South Africa’s leaders to keep the country united and prosperous in the decades to come — to ensure that South Africa continues to be, as Mandela memorably stated in his 1994 inaugural address, ‘a rainbow nation, at peace with itself and the world.’

South Africa today remains the jewel of sub-Saharan Africa, in both humanitarian and economic terms. Mandela’s release from prison and the largely peaceful negotiation of the end of apartheid in Africa alongside F.W. de Klerk, South Africa’s president from 1989 to 1994, rank among the most memorable events of the 20th century. The constitution that Mandela helped to enact in 1996 is one of the world’s most progressive in terms of human rights — it purports to grant every South African the right to human dignity, to health care and water, to work, to a basic education, to housing. Even if the rights promulgated in the South African constitution today remain more aspirational than functional, the constitution was pathbreaking in it breadth. It’s notable that in 2006, South Africa became the fifth country in the world to allow same-sex marriage.

With an economy of $579 billion (on a PPP basis, as of 2012, according to the International Monetary Fund), South Africa has the largest economy on the entire African continent, despite the fact that its population of 53 million is dwarfed by the populations of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (67.5 million), Ethiopia (86.6 million) and Nigeria (a staggering 173.6 million).

Its GDP per capita of $11,281 (again on a PPP basis and as determined by the IMF as of 2012) is exceeded in sub-Saharan Africa only by oil-rich Gabon ($18,501) and tourism hotspot Botswana ($15,706), and it far outpaces the fourth-ranked Namibia ($7,500) and the fifth-ranked Angola ($6,092), another petrostrate. Even that understates South Africa’s economic dominance, because both the Botswanan and Namibian economies have flourished in large part due to trade with the South African economy.

But that doesn’t mean all is perfectly well. Nigeria seems likely to outpace South Africa to become the largest sub-Saharan African economy soon, if it hasn’t already. Despite its status as Africa’s economic powerhouse, South Africa suffered its first post-apartheid recession in 2009, and the recovery hasn’t been particularly strong. South African GDP grew just 2.2% last year and growth remained sluggish this year, too. Unemployment is creeping downward, but it’s still a whopping 24.7% as of the third quarter of 2013. Different studies make it difficult to know whether poverty is rising or declining, but wealth among South African whites is massively higher than wealth among South African blacks, and income inequality is rising sharply in South Africa (as in much of the rest of the world).

Clashes between miners and South African police during last summer’s Marikana strike left 34 people dead, shocking both South Africa and the world with the kind of violent images that hadn’t been seen in South Africa since the apartheid era.

With an estimated HIV/AIDS rate of 17.5%, South Africa has the world’s fourth-highest HIV prevalence after neighboring Swaziland, Lesotho and Botswana. Though we now recognize Mandela as one of the world’s most prodigious activists in the campaign against HIV/AIDS, the issue wasn’t at the top of his agenda as president, a failing that Mandela acknowledged after leaving office. In retirement, however, Mandela took up the cause with vigor (especially after his own son Makgatho died from AIDS complications in 2005). His forceful push at the 2000 AIDS conference in Durban muted the criticisms of the Mbeki government and paved the way for greater treatment options for all Africans, including South Africans. But the much-delayed fight against HIV/AIDS represents one of the starkest failures of post-apartheid South Africa.

Most troubling from a political standpoint, after 19 years of rule by the governing African National Congress (ANC), there’s still no clear alternative for South African voters in the upcoming election, notwithstanding disappointment in widespread corruption, the tepid economy, Marikana and other ANC failures. Despite the fact that South Africa is a multi-party democracy, the ANC continues to win lopsided electoral victories while the main opposition party, Democratic Alliance (DA), is viewed, fairly or unfairly, as the party of disgruntled white South Africans.

Racial voting patterns have proven almost impossible to break in South Africa, with black South Africans largely supporting the ANC and with the DA winning most of its support from white South Africans and coloured South Africans (mixed-race voters who live largely in the Western half of the country). Considering that white and coloured South Africans each comprise just 9% of the total population, that means there’s a low ceiling for DA support. Under the leadership of former journalist, anti-apartheid activist and former Cape Town mayor Helen Zille, the DA won 16.66% and 67 seats in South Africa’s unicameral National Assembly in the most recent 2009 general election. While that’s far below the 65.90% and 264 seats that Zuma’s ANC won, it marked the strongest performance in a general election for the DA to date. Moreover, in the 2011 local elections, the DA won 24% of the proportional vote and won control of virtually all of Western Cape province. It seems unlikely that Zille can, by herself, power the DA to an outright victory next spring, but expectations are high that she can deliver another record-high result for her party.

The remaining established opposition parties are crumbling. The Inkatha Freedom Party, an ANC rival within the anti-apartheid movement in the 1970s and 1980s, has lost support from its traditional Zulu-speaking constituency in KwaZulu-Natal. As the party dropped from 10% support to under 5% support in the 2009 election against Zuma (who himself is Zulu), it has since split into two factions. The same fate befell the Congress of the People (COPE), a faction of old-guard ANC grandees who formed a new party under leader Mosiuoa Lekota to oppose Zuma in 2009 — though the group won nearly 7.5% of the vote, it too has collapsed under the weight of internal factions.

That means that the likeliest route to a true two-party system might yet come from a split among the core ANC electorate. Though Zuma handily defeated deputy president Kgaleme Motlanthe (who served briefly as South Africa’s caretaker president between September 2008 and May 2009) in the ANC’s 2012 leadership contest, Zuma seems to be grooming as his successor Cyril Ramaphosa, a former union activist who played a key role in the negotiations that ended apartheid. After losing a power struggle within the ANC to Mbeki in 1997, Ramaphosa left politics in favor of a successful business career, but returned as deputy president of the ANC in December 2012, replacing Motlanthe. Ramaphosa is likely to become South Africa’s next deputy vice president after the 2014 elections — if so, expect him to take an increasingly important role in South African policymaking.

Mamphela Ramphele, a well-known anti-apartheid activist whose partner Steve Biko was killed in police custody in the 1980s, has formed a new party, AgangSA (Agang is a Sotho word meaning ‘to build’) that will contest next spring’s election. Though Ramphele’s party seems unlikely to emerge with a real chance at winning power, Ramphele, who has served as a managing director of the World Bank, commands a great deal of respect from traditional ANC constituencies due to her links to Biko. Her new party is campaigning mostly in Gauteng province (home to Johannesburg and Pretoria), Limpopo province and the Eastern Cape province, but it remains to be seen if her good-government, ‘transcending race’ campaign can attract significant support.

Former ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema, who was pushed out of the ANC after his convictions for hate speech (stemming from his singing of ‘Dubula iBunu,’ (which translates to ‘Shoot the Boer’) has launched his own ‘protest movement,’ the Economic Freedom Front (EFF). Malema, who had previously been a rising star in the ANC, personifies an even more populist approach to politics than Zuma, and he’s advocated relatively radical positions in favor of land redistribution from white South Africans to black South Africans and nationalization of key South African industries. Though it’s more reminiscent of the young Mandela than the statesman-like Mandela of his final decades, Malema’s platform could appeal to South Africa’s poorest and most disillusioned supporters impatient with waiting for economic justice after years of ANC failures.

While everyone believes that Zuma will lead the ANC to another landslide win in the 2014 election, the emergence of Ramphele, Malema and Ramaphosa could all precipitate the kind of fracturing that could lead to a wide-open race in 2019. Whether any of them have the power to meet the challenges of post-Mandela South Africa is still an open question.

Photo credit to Jerome Delay/Associated Press.

3 thoughts on “How Nelson Mandela’s death provides South Africa a challenge and an opportunity”