Earlier this week, Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh announced his choice to head the Reserve Bank of India — Raghuram Rajan, a University of Chicago economics professor who’s perhaps best known for cautioning in 2005 that the financial system was headed toward a collapse.![]()

Rajan will certainly face quite a difficult set of problems — notably the sharp decline in the value of the Indian rupee this year.

But when Rajan takes over as RBI governor in September, he will also immediately become one of the chief actors in determining the outcome of India’s scheduled May 2014 national elections. While the world is naturally asking the question, ‘How will Rajan strengthen the rupee?’, it should also be asking, ‘How committed is Rajan to helping Singh’s Congress Party win a third consecutive election?’ and ‘What kind of relationship might Rajan have with prime minister Narendra Modi?’

Rajan will certainly face pressure from within the current government to help ease the economy into the 2014 election, perhaps by lowering the RBI’s bank interest rate from 7.25% to spur growth over the next eight months. But Rajan’s more immediate problem is arresting the Indian rupee’s 12% decline in the past three months, not to prop up Singh’s government, and it’s not even clear that Rajan can do anything to boost growth without exacerbating other problems. Furthermore, Rajan’s long-term interest in liberalizing India’s economy will also give Modi a powerful ally if elected.

India’s current United Progressive Alliance (UPA) coalition government is unpopular and Singh, India’s prime minister since 2004, will cede the spotlight to Rahul Gandhi, a somewhat lackluster fourth-generation member of the powerful Nehru-Gandhi family that dominates the ruling Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस). One of the reasons that Singh and Congress are so unpopular is the slowdown in India’s economy over the past five years — GDP growth has dropped from a galloping 8.5% in 2009 and 10.5% in 2010 to just 6.3% in 2011, 5.4% in 2012 and an estimated 5% or so in 2013.

Furthermore, Singh has not been as successful as prime minister in enacting the kind of ‘big bang’ liberalization reforms as he was in the early 1990s, when Singh served as finance minister under prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao. Singh’s push last year to liberalize India’s retail sector and to cut fuel subsidies, met with fierce resistance from just about everyone in India — the political left in his own coalition, including West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee, who withdrew her support from Singh’s government; the political right, which supported reforms when it was in power in the early 2000s; and India’s labor unions and India’s many small shopkeepers. While Singh deserves credit for enacting the retail reforms, they fall far short of what Singh was expected to have accomplished when he took office nearly a decade ago.

Modi is the longtime chief minister of Gujarat, a state that boasts a particularly strong economic record, and he exudes more energy than just about anyone in Singh’s government these days. Modi will lead the conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, or भारतीय जनता पार्टी) into next year’s election. Though he remains controversial within India and abroad due to his role in Hindu-Muslim rioting in 2002, he stands a good chance of becoming prime minister. Modi is certainly enthusiastic about further liberalization reform in India, which makes Rajan a natural ally. While there is certainly room for much more liberalization in the Indian economy, there are plenty of protectionist voices within the BJP (many of whom objected to Singh’s retail market reforms), to say nothing of Congress and more leftist Communists in the Indian parliament, who are certain to oppose reform.

Ironically, it could be Modi who finishes the work that Singh-the-finance-minister began.

Also ironically, it could be Singh’s appointment this week that hands Modi a key ally within the central bank to enact more liberalization.

None of that will necessarily matter, however, if Rajan cannot stop the rupee’s plummet in value, which has made it more expensive for India to import oil and other goods. That has created two immediate problems for India’s economy.

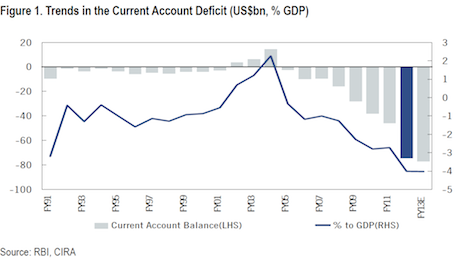

First, India’s current account deficit is plummeting — i.e., India is consuming more from abroad than it produces at home:

As the rupee has fallen, the higher cost of imports has accelerated India’s current account imbalance. Much of the problem lies in Indian demand for gold imports, which constitute nearly three-fourths of India’s current account deficit. But it’s not about bling as much as it’s about the fact that hundreds of millions of rural Indians lack formal access to banking, so gold represents the safest and easiest means of saving. That’s why the Indian government is encouraging Indians to stop buying gold from abroad. Although India raised the tariff on gold imports from 4% to 6% and although the RBI is toying with the idea of instituting gold-backed savings funds for Indians (the idea is to reduce imports by creating a kind of domestic gold exchange), demand for gold has remained steady. That’s intuitive enough — even if you have access to a bank account, if you’re a farmer in Bihar state and the rupee keeps on losing purchasing power, of course you would rather invest your savings in a hard metal like gold instead of a drooping currency. But as the currency keeps drooping, the rupee price of imported gold rises, which just makes the current account deficit worse. That, in turn, makes India’s economy seem even weaker in the eyes of global investors, including currency traders, possibly pushing the rupee even lower.

Second, the rupee’s decline is fueling inflation — as the price of oil, in rupee terms, rises, it forces the price of everything else higher.

While Rajan’s predecessor Duvvuri Subbarao has worked hard to stem India’s core inflation from around 10% to just under 5% today, the kinds of inflation that are most likely to affect everyday Indians remain persistently higher — consumer price inflation remains stuck at around 10% and food inflation nearly 15%. That indicates that Subbarao perhaps lowered interest rates too soon from a high of around 8.5% in January 2012.

(Third, you might add that the rupee’s decline also makes India’s worrisome public debt burden — between 50% and 60% of GDP — more unsustainable).

To make matters worse, the rupee’s decline may have more to do with global capital flows than the weakening fundamentals of India’s economy. The U.S. Federal Reserve’s efforts to keep interest rates at essentially zero since autumn 2008 arguably spurred a bubble in emerging market investments. Investors, facing no substantial return in the United States, turned to the developing world instead, fueling Indian growth in the years immediately following the global financial crisis. With the Fed now signaling that it may taper its quantitative easing next year or in 2015, global investors may already be redirecting more investment back into the United States and away from the developing world, thereby deflating not only the rupee, but other currencies as well.

But it doesn’t matter if global forces or domestic forces are pushing the rupee’s value down, it’s the RBI’s problem — and now Rajan’s problem — all the same.

So while Rajan might be able to goose the economy by lowering interest rates, those gains are likely to be erased by exacerbating Indian inflation and discouraging higher returns on foreign investment, thereby worsening India’s rupee problem. It’s not clear what Rajan could actually do to boost Congress’s chances, even if he were so inclined.

Before this week, Rajan was probably best known for having authored two particular notorious articles. The first is a 2005 paper suggesting that the proliferation of novel finance products and loose monetary policy risked causing a financial crisis (Rajan looked prescient with hindsight, but former U.S. treasury secretary Lawrence Summers famously dismissed Rajan at the time as ‘slightly Luddite.’).

But it’s his 2012 article in Foreign Affairs that is more applicable to his new job as central bank governor. In that article, he suggested Western governments should not use deficit spending to boost their economies, but instead enact structural reforms and retrain workers to be more competitive. In writing the article, Rajan jumped headlong into a fraught debate among U.S. and global economists, angering Paul Krugman and other well-known Keynesian economists.

But the relevance of Rajan’s views to India is clear — as RBI governor, Rajan will be keen on promoting the liberalization of India’s economy, and Rajan’s prescriptions for long-term growth are much more compatible with a potential Modi government than with another Congress-led government.

6 thoughts on “Raghuram Rajan’s selection as India’s new central bank governor is good news for Modi”