Just a little over a year after the second of two divisive elections in Greece, the smallest partner in the three-party governing coalition withdrew its support today — leaving Greece ever closer to new elections, though the government will continue on with a slim majority for now.![]()

Fotis Kouvelis, in announcing that his party, the Democratic Left (Δημοκρατική Αριστερά), would leave the coalition over the growing row related to the sudden closure of ERT, the national broadcaster, emphasized that Greece did not need new elections, and he indicated that the party would perhaps provide external support to what’s left of prime minister Antonis Samaras’s coalition to keep Greece on track with respect to the terms of its bailout program with the ‘troika’ of the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

What does that mean for Greece?

Though it’s true that the departure of the Democratic Left doesn’t necessarily mean new elections, it leaves the government in a precarious position.

Samaras’s New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία), Greece’s longstanding center-right party, holds 125 seats in the 300-member Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Its other coalition partner, PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα), Greece’s traditional center-left party, holds 28 seats. Together, that gives the government an ostensible three-seat majority, though the 14 seats that Kouvelis delivered provided a wider margin for comfort over a year that’s seen Samaras’s government push forward with the fiscal adjustments mandated by the bailout program.

But more importantly, Kouvelis (pictured above, left, with Samaras in center background) delivered the votes of one of the two parties of the anti-bailout left, giving Samaras’s government a broader base and a credible claim to being somewhat of a unity government.

The Democratic Left formed only in 2010 when moderates split from the leftist SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς). So while SYRIZA leader Alexis Tsipras is content to lead the opposition, Kouvelis and his party brought an outsized amount of legitimacy to Samaras’s government. After all, both New Democracy and PASOK had backed Greece’s bailouts, and many voters have held the two parties, which switched back and forth in power in recent decades, especially responsible for Greece’s economic woes.

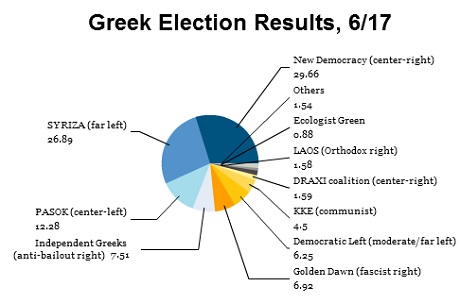

Their continued unpopularity is one reason why no one wants to risk elections anytime soon. PASOK, in particular, has lost nearly all of its support among voters to the benefit of Tsipras and SYRIZA, which have given more muscular voice to the anti-bailout left. If elections were held tomorrow, it’s not even certain that PASOK would pass the 3% threshold to win seats in the Hellenic Parliament.

One recent poll shows New Democracy holding onto a very narrow lead, with 21% to just 20.5% for SYRIZA. In third place is the neo-fascist Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή) with a staggering 10.2%. Greece’s far-left Communist Party (KKE) registered 5.7%, the center-right (but anti-bailout) Independent Greeks registered 5.2%. PASOK won just 5.1%, and the Democratic Left won just 4.8%.

With such weak support, neither Samaras nor PASOK leader and former finance minister Evangelos Venizelos have an incentive to trigger new elections. So while the chances that Greece will go to the polls for the third time in 12 months are slim, there’s no escaping the fact that the Democratic Left’s decision to leave the government is a setback for Samaras. Continue reading Kouvelis, Democratic Left withdrawal from Greek government leaves precarious majority