When the European Union expanded Regulation 1236/2005 in December 2011, its regulators could hardly have known that it would lead, in part, to the excruciating scene of a failed 43-minute execution in McAlester, Oklahoma.

The EU decision expanded an existing ban on the trade of instruments used for torture to include those drugs specifically used by US state correctional facilities to execute prisoners by means of legal injection. It codified at the EU supranational level what had already become a growing practice at the national level in Europe, including in the United Kingdom, arguably the closest international US ally.

it served a laudable goal from the European perspective — making it more difficult for state governments in the United States to import the necessary drugs in the traditional three-drug cocktail used by most states for nearly four decades to execute inmates by lethal injection.

What’s more, that decision is the latest example of how the European Union’s policies are increasingly affecting the United States — from antitrust law to data privacy to trade harmonization, European regulatory standards will continue to shape US policies and outcomes in new and, for some Americans, often frustrating ways.

As a matter of human rights, both the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights denounce and ban the death penalty within the European Union. But the death penalty’s abolition goes beyond the immediate boundaries of the European Union — it’s banned almost universally across Europe, with the single exception of Belarus. Even Russia, which isn’t exactly the best-practices touchstone for human rights, has implemented a moratorium. Russia’s last execution took place in 1996. France’s last execution (yes, by guillotine) took place in 1977. Italy’s last execution (by firing squad) took place in 1949. The last UK execution (by hanging) took place in 1964. The entire era of executions by ‘lethal injection,’ which largely followed the US Supreme Court’s four-year moratorium* on capital punishment over concerns that executions violate the eighth amendment ban on ‘cruel and unusual punishment,’ comes largely after Europe abolished the death penalty. By the time that lethal injections became the standard practice for executions, Europe was largely out of the execution business.

Since 1977, execution by lethal injection in the United States has involved the use of three drugs:

- sodium thiopental, an anesthetic that is used to render the convicted person unconscious;

- pancuronium bromide, which is used to paralyze the subject and stop breathing, in part for the benefit of the audience observing the execution, because it provides the appearance that the victim isn’t suffering; and

- potassium chloride, which stops the heart and, in theory, rapidly leads to death.

Ironically, the two most potent drugs are widely available. It’s sodium thiopental that’s become so difficult for state governments to obtain under the new EU regulations. With sources of sodium thiopental becoming increasingly scarce, correctional facilities are turning to some fairly desperate measures to avoid disruption of their regularly scheduled executions. In some cases, that’s meant sourcing drugs through illegal channels, and in other cases, that’s meant that states, like Oklahoma, have experimented with new combinations of drugs. When Missouri contemplated using propofol instead, European countries started talking about banning that drug’s export, too, which led to a deluge of concern among US health professionals that they would lose access to one of the most important anesthetics in medical use today. Missouri’s governor Jay Nixon quickly moved away from the idea.

As Matt Ford reported for The Atlantic earlier this year, EU efforts won’t necessarily end the death penalty in the United States, but they are certainly complicating its efficacy:

“The EU embargo has slowed down, but not stopped executions,” Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C, told me. “It has made the states seem somewhat desperate and not in control, putting the death penalty in a negative light, with an uncertain future.”

That’s left the United States where it is today. States like Oklahoma, determined to move forward with executions, are left with few good options. Experimenting with new drugs will invariably lead to more botched executions like Tuesday night’s execution of Clayton Derrell Lockett (though it’s worth noting that lethal injections, and all executions, are potentially imperfect from an Eighth Amendment perspective — Ohio learned this in 2009 with the failed execution of Romell Broom).

But the EU decision has also led to more astonishing measures. Oklahoma has taken extraordinary steps to keep secret the contents of its new experimental execution cocktail — if EU member-states discover which drug Oklahoma is using, they could easily ban that drug as well. Notwithstanding the fears that the drugs might cause the kind of 43-minute, tortured death that Lockett actually suffered last night, Oklahoma governor Mary Fallin (pictured above) brought the state to the brink of political crisis over the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision to stay the execution earlier this month. Only after some of Fallin’s Republican colleagues in the Oklahoma legislature threatened to impeach the justices did they relent.

Whatever you think of the death penalty and its continued use in the United States, it’s difficult to believe that it’s worth undermining the judiciary’s independence on a matter of life-and-death constitutional rights or that it’s worth turning the penultimate expression of law and order, an irreversible deterrent, into a tortured science experiment.

It’s even harder to believe that in a 21st century liberal democracy with strong freedom-of-information traditions, a state government can legally keep secret the means of executing its own citizens.

If former Illinois Republican governor George Ryan, who placed a moratorium on Illinois’s death penalty in 1999, represents the sober view that the capital punishment is simply too flawed to be effective, Fallin will now become the symbol of the opposite — denying the basics of due process or constitutional rights all in the service of tinkering with the machinery of death, as the late Supreme Court justice Harry Blackmun wrote in a scathing 1994 denunciation of capital punishment. Continue reading How EU regulation led to Oklahoma’s ghastly botched execution →

![]()

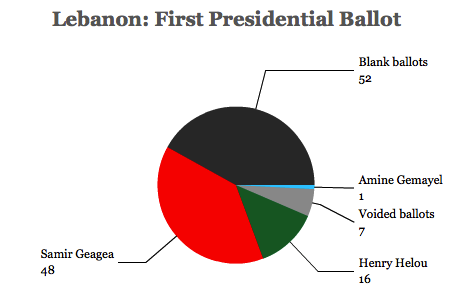

With the term of Lebanese president Michel Suleiman set to expire on May 25, the country’s 128-member parliament will convene tomorrow, April 23, for the first of what will likely be weeks of voting and negotiating to select a replacement.

With the term of Lebanese president Michel Suleiman set to expire on May 25, the country’s 128-member parliament will convene tomorrow, April 23, for the first of what will likely be weeks of voting and negotiating to select a replacement.