If there’s any positive monument to the US-led occupation of Iraq, it’s the relative autonomy and stability of Iraqi Kurdistan, the northern sliver of Iraq.![]()

![]()

Iraqi Kurds are voting in a parliamentary election today that’s likely to have profound consequences for the future governance of a region that serves as a bulwark against the sectarian conflict in the south of Iraq, a government in Turkey to the north that remains largely unfriendly to the Kurdish minority and a civil war to the west in Syria.

The election is notable because the Kurdish president of Iraq Jalal Talabani, who is more responsible for today’s autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan than any other Kurdish politician, lies ill in Germany after suffering a stroke last December. Talabani’s absence makes it likely that the pro-independence party he founded in 1975, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK, یەکێتیی نیشتمانیی کوردستان) will suffer losses in today’s election.

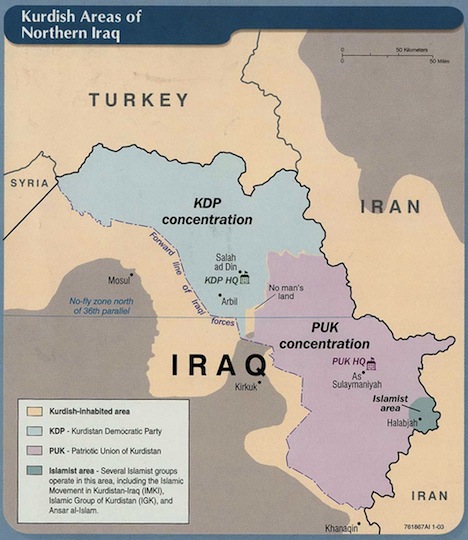

It’s also notable because, for the first time since Iraqi Kurdistan gained autonomy, the PUK and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP, پارتی دیموکراتی کوردستان), will run on separate tickets after an often uneasy alliance first struck in 1992 — the two parties ran on joint tickets in the previous 2005 and 2009 elections, with a joint KDP/PUK administration. KDP leader Masoud Barzani (pictured above, left, with Talabani, right) has served as president of the Iraqi Kurdistan region since 2005.

Home to between 5.5 million and 6.5 million of Iraq’s 31 million residents, Iraqi Kurdistan first obtained autonomy in the early 1990s after the sustained efforts of Kurdish nationalist figures like Talabani in the 1970s and the 1980s, when Iraqi Kurds found common cause with Iranian Kurds during the horrific Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s. After the imposition of a no-fly zone by US-led forces in the aftermath of the Persian Gulf War, Iraqi Kurdistan started to emerge from the iron-fisted rule of Ba’athist strongman Saddam Hussein.

The Kurdish government and the national Iraqi government continue to fight over the sharing of oil revenue and internal territorial disputes, especially from near Kirkuk, where Kurds constitute around 50% of the population, though it lies technically outside of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. Nonetheless, Iraqi Kurdistan’s autonomy was cemented with the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 that toppled Saddam. Even as the rest of Iraq crumbled into civil war between Sunni and Shiite militia, Kurdish Iraq only strengthened and Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, became one of the few peaceful urban centers in Iraq. Talabani, who is a Sunni Muslim, became the president of Iraq in April 2005, as an Iraqi leader with primary associations to his Kurdish identity than to the already toxic sectarian rift between Sunni and Shi’a that would come to dominate the rest of the 2000s.

Back in Iraqi Kurdistan, however, Talabani’s party joined forces with the KDP, a party with even deeper roots in the Kurdish independence movement — the KDP had its roots in the Soviet-backed Kurdish national movement of the 1940s. The KDP originally welcomed the first Ba’athist coup in 1963 and the subsequent successful 1968 coup that installed the Ba’athist regime in Iraq, including Saddam, initially as vice president. But mutual enthusiasm soured on both sides, especially in light of Iranian assistance for the KDP, culminating in the KDP’s military effort against Saddam’s regime between 1974 and 1975. That Kurdish-Iraqi War ended in defeat for the KDP and many top KDP leaders fled to exile in Iran, opening the way for the emergence of Talabani and the PUK.

An ongoing power struggle between the KDP and the PUK turned into fully armed civil war between 1994 and 1997. But by the time of the 2003 Iraqi invasion, the PUK and the KDP found common cause in an opportunity to grab Kurdish autonomy once and for all. The two parties have governed, not always harmoniously, ever since, with the PUK’s Talabani holding power as the president of a federal Iraq and the KDP’s Barzani holding power back home in the Kurdish region. Barzani is the son of the KDP’s founder, Mustafa Barzani, and his family is one of the most important in Iraqi Kurdistan, despite the family’s exile to Iran in the 1970s and 1980s.

In the previous 2009 elections, a third force emerged to challenge the KDP/PUK hegemony — Gorran, or the Movement for Change (بزوتنهوهی گۆڕان), which won 25 seats in the 111-member Perleman, the Kurdish parliament. Talabani’s absence means that Gorran hopes to make even more inroads, especially in the PUK’s heartland in southern Iraqi Kurdistan.

While they won 59 seats together in the previous elections, their relative strengths aren’t much greater than Gorran’s — the KDP holds 30 seats by itself and the PUK just 29. Other parties hold 27 seats in the Kurdish parliament, including three Islamist parties (the strongest is the Kurdistan Islamic Union, which has ties to the regional Muslim Brotherhood) that won 12 seats and including 11 seats set aside for ethnic and religious minorities, including Assyrians, Armenians, Turkmens and other Christians.

Given the fragmentation of the Kurdish political scene, and given the longstanding and unwavering support that each of the KDP and the PUK commands in their heartlands (the KDP in northern Kurdistan and the PUK in southern Kurdistan), no single group is likely to win an absolute majority. That means today’s election could result in any of four possibilities: a renewed PUK/KDP administration, an ‘opposition’ administration led by Gorran with support from perhaps minority or Islamic groups, a PUK/opposition coalition or a KDP/opposition coalition.

Though the potential end of the longtime PUK/KDP unity may be some cause for apprehension in light of the peace that the Kurdish administration has maintained for the past eight years, the development of a competing marketplace for Kurdish voters is the natural next step in the democratic development of Kurdistan — and a chance to break up the increasingly cozy oil-fueled corruption within both the PUK and the KDP.

2 thoughts on “Bordered by chaos, Iraqi Kurdistan holds elections in relative oasis of peace and democracy”