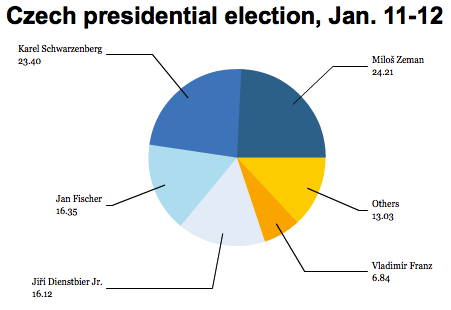

In his first 100 days in office, Miloš Zeman, the former social democratic prime minister who became the Czech Republic’s first elected president, made it clear that he intends his role to be much more powerful than a merely ceremonial head of state, pursuant to a Czech constitution that gives somewhat more power to the presidency than in neighboring countries like Germany, Poland or Italy.![]()

But with the resignation of prime minister Petr Nečas, Zeman has an opportunity to imprint his vision of government on the Czech Republic beyond what he might have expected when he was elected in January 2013 over the aristocratic center-right foreign minister Karel Schwarzenberg.

Nečas’s resignation on Monday capped a fast-moving weeklong drama in Czech politics that has plunged the country of 10.5 million citizens into a period of uncertainty.

The crisis began last week with an unprecedentedly wide police raid of government offices that resulted in the arrests of eight government officials, including Nečas’s chief of staff, Jana Nagyová. Though corruption has long been issue in Czech government, it often goes unpunished, and when corrupt officials are charged, they are rarely arrested in such a sweeping and high-profile manner. Milan Kovanda, head of Czech military intelligence, and his predecessor Ondrej Páleník, were both arrested as well.

Nečas (pictured above) announced last week that he is divorcing Radka Nečasová, his wife of three decades and mother of his four children. But he has long been rumored to have had a romantic relationship with Nagyová, who is accused of bribery and abuse of power for allegedly having military spies follow Nečas’s wife. The widespread belief that Nagyová is believed to have committed crimes that are associated with her relationship with Nečas made his position as prime minister increasingly difficult. That, in turn, led to Nečas’s capitulation on Monday when he announced he would step down as prime minister and as leader of the Czech Republic’s main center-right party, the Občanská demokratická strana (ODS, Civic Democratic Party). Nečas will remain as a caretaker prime minister until a new government is formed.

The center-right ODS has governed in coalition with Schwarzenberg’s liberal Tradice Odpovědnost Prosperita 09 or ‘TOP 09′ (Tradition Responsibility Prosperity 09) and with various members of a third, minor conservative party, Věci veřejné (VV, Public Affairs), since the May 2010 election, though the government nearly lost power when its smallest partner Public Affairs nearly imploded in 2012 over its own corruption scandals. Despite Nečas’s resignation, Schwarzenberg’s allies want to try to form a new government under deputy ODS chairman Martin Kuba, the current trade and industry minister, that will continue to govern through the end of the current parliamentary term in May 2014.

ČSSD leader Bohuslav Sobotka, however, is calling for early elections and has promised that any new ODS-led government will meet with a vote of no confidence that Kuba is not certain to win.

The decision rests entirely in Zeman’s hands — he can give Kuba a mandate to form a new government, he can call early elections, or he could try to give the mandate to Sobotka or, more likely, a technocratic government that would be expected to do Zeman’s bidding for the next 11 months.

Though ODS holds 53 seats and TOP 09 holds 41 seats, the Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD, Czech Social Democratic Party), with 56 seats, has the greatest number of seats in the 200-seat Poslanecká sněmovna (Chamber of Deputies), the lower house of the Czech parliament. Zeman, a former ČSSD leader and prime minister from 1998 to 2002, broke with the ČSSD in 2009, and the ČSSD sponsored an alternative candidate for president earlier this year in Jiří Dienstbier Jr., a young senator, rising star and son of a famous Czech dissident. But since becoming president, Zeman has taken steps to realign himself with the ČSSD, speaking to the party’s annual congress in March 2013 and otherwise worked to bridge the gap between with the current ČSSD leadership.

Though Schwarzenberg emerged as a surprisingly strong contender for the presidency in January, the ODS candidate finished in eight place with less than 2.5% of the vote in the first round of the presidential election. The party remains relatively unpopular after implementing an all-too-familiar austerity program of tax increases, budget cuts and reductions in government services alongside an economy that contracted by an estimated 1% in 2012 and that features a rising unemployment rate that’s currently at 7.3%. The fantastic scandal over the past week that’s now ended Nečas’s career came when the ČSSD was already in a strong position in advance of the next parliamentary elections — polls show the ČSSD with a wide lead. One poll last month gave the ČSSD 24% support, with the more leftist (though increasingly a potential ČSSD coalition ally) Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy (KSČM, Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia) far behind in second place with just 10.5% support, with TOP 09 at 9.5% support and the ODS with 9% support.

Zeman, who passed the 100-day mark of his presidency just last week, has taken an aggressive posture as president, convinced that the fact of his direct electoral mandate (unlike past presidents Václav Havel and Václav Klaus, who were elected indirectly by the Czech parliament) gives Zeman more authority to assert himself over the Czech government. He immediately set out to boost Czech ties with the European Union by flying the EU flag at Prague Castle, the presidential residence, and signing amendments to the EU Treaty of Lisbon, both of which marked a 180-degree turn from the relatively antagonistic EU policy of Klaus, his immediate predecessor. He’s also tangled with Schwarzenberg over the right to name the country’s ambassadors.