Sometimes, the cruelest cuts in international politics come not only from within your own party, but from within your very own family.![]()

Just ask David Miliband.

After months of increasingly strained relations, however, Marine Le Pen has now engineered the first break yet with her controversial father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, when he was formally ousted last week from the party that he founded, the far-right Front National (National Front). The legal move followed a political move earlier in the summer, when 84% of the party’s 30,000 followers also voted to expel Jean-Marie from the party that he founded in 1972.

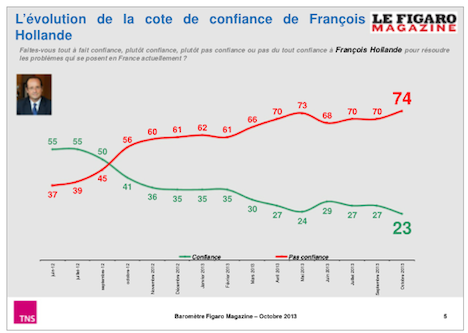

In one sense, the Le Pen family spat has been a distraction from Marine Le Pen’s long-term goals of projecting her party as the true heir to French conservatism and building a majoritarian coalition that can woo not only traditional right-wing voters but left-wing voters disenchanted with French president François Hollande and the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) and the neoliberal economic prescriptions that now dominate policymaking within the eurozone.

Since her party easily outpaced the ruling Socialists and Sarkozy’s center-right party in the May 2014 European parliamentary elections, Marine Le Pen has spent much of 2015 feuding with her own father.

* * * * *

RELATED: Marine Le Pen is still a longshot

to win France’s presidency in 2017

* * * * *

What’s worse, the spat showcases just how problematic it can be when a political party becomes tied up too strongly in family dynasty — it’s as true for the French right as for Indian secularism or Canada’s center-left. As Marine tries to consolidate the Front’s rank-and-file under her leadership, with regional elections approaching in the autumn, her niece Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, the 25-year old MP from southern France, could still make her life difficult.

Maréchal-Le Pen (pictured above) has been more sympathetic to her grandfather and, unlike Marine’s journey toward economic nationalism, popular in northern France, Marion is far more of a traditional economic liberal and, with her southern base, far more focused on immigration. In December, Maréchal-Le Pen will be running for the presidency of the Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur region; Marion Le Pen, for her part, will be contesting the presidency of the northern Nord-Pas-de-Calais region. The party will be watching keenly to see which variety of the Front‘s politics will be more successful.

But in another sense, tossing the 87-year-old Jean-Marie Le Pen to the side in 2015 could help Marine in 2017 as she continues to remake the party’s image — and brand it further away from the often anti-Semitic tones of her father’s leadership, which was also rooted in his experience as a soldier fighting to defend France’s colonial holdings in Algeria. Remarks about Nazi gas chambers being just a ‘detail of history,’ as it turns out, do not go down well for Marine’s push for a Front sanitaire.

Marine’s mission

Instead, Marine Le Pen is forging an identity that blends welfare-heavy statism, social conservatism and a nationalism that rejects both immigration and European integration. There’s a reason it’s called populism. Rallying support for ‘a strong France’ and opposition to a feckless European superstate that now essentially dictate France’s monetary, justice and border control policy, championing the comfort of an unreconstructed cradle-to-grave social welfare and attacking the ‘other’ of eastern European, African and Middle Eastern immigrants has an undeniably popular allure to many voters whose economic futures are far less certain than they were two generations ago. It’s attracted some odd supporters, including a puzzlingly high number of urban LGBT voters — Marine’s chief adviser, Florian Philippot, and the architect of Marine’s anti-eurozone policy, is openly gay. While Marine discreetly avoided the most intense battles of the same-sex marriage fight in 2013, Maréchal-Le Pen embraced the opposition to marriage equality.

That means that Le Pen has found common cause in recent years with a strange number of odd political bedfellows. That includes Nigel Farage, the anti-immigrant head of the United Kingdom Independence Party, who encourages a British exit from the European Union in the 2017 referendum, and Geert Wilders, the anti-Islam and anti-immigrant crusader of Dutch politics. But she also encouraged Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras in his standoff with European finance ministers over Greek debt relief (though Le Pen rejected him in stark terms when he agreed in July to enter negotiations for a third bailout for his country). She has also voiced sympathy for Russian president Vladimir Putin in his two-year quasi-standoff with Ukraine.

Marine’s bet seems to be working as French voters begin to focus on the contours of what could be an unpredictable presidential election in May 2017. In IFOP’s latest August 2015 poll, Le Pen leads all contenders for the first-round vote, garnering 26% in a race against Hollande (20%) and former president Nicolas Sarkozy (24%), guaranteeing her a spot in a runoff against Sarkozy. Though her father made the runoff in the 2002 presidential election against then-president Jacques Chirac, Jean-Marie Le Pen only narrowly managed a second-place victory over the Socialist candidate, prime minister Lionel Jospin. Continue reading How the Le Pen family feud influences France’s 2017 election