Voters in two of India’s largest states elected regional assemblies last week on October 15 — in Maharashtra and Haryana.![]()

In both cases, the conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) will take power of state government for the first time in Indian history in what was the first major electoral test for prime minister Narendra Modi (pictured above), who swept to power nationally in May after promising to bring a new wave of economic prosperity, reform and good governance to India.

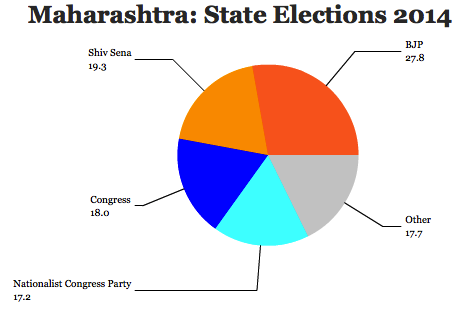

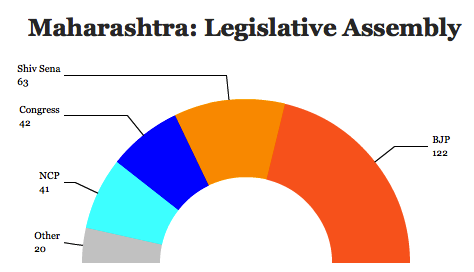

In Maharashtra, India’s second-most populous state, with over 112 million people, and home to Mumbai, India’s sprawling financial and cultural center, the BJP won a plurality of the vote and the largest number of seats in the 288-member regional assembly, where it will form a coalition government with either its longtime ally, the far-right, Marathi nationalist Shiv Sena (शिवसेना) or a more intriguing option, the center-left Nationalist Congress Party (NCP, राष्ट्रवादी कॉँग्रस पक्ष), which unexpectedly offered to support a BJP government shortly after the results were announced on October 19:

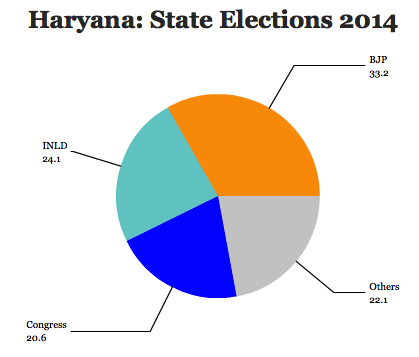

In Haryana, a state with just 25.4 million people, which forms much of the hinterland of New Delhi, the BJP won an outright majority of seats in the 90-member legislative assembly:

There are at least four narratives about what happened in these two absolutely pivotal state elections, the first since India’s national election cycle in April and May. Keep in mind that, together, the two states have a population of 137 million, larger than Japan.

The first narrative confirms the BJP’s political dominance in the honeymoon period of the Modi era. The second narrative is its direct analog, the post-independence nadir of the Nehru-Gandhi family and the chief opposition party, the Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस).

The third narrative, with almost as much national importance as the first two, is the rift between the BJP and its longtime ally, Shiv Sena, and the possibility that Shiv Sena will be shut out of the next Maharashtra government.

The fourth and final narrative has to do with India’s third parties, especially as the election relates to the anti-corruption Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी, Common Man Party), which didn’t even bother contesting the Haryana elections and may soon lose its one-time grip on Delhi’s government.

1. Above all, October’s state elections are a huge victory for Modi.

It’s impossible to understate how historic the Maharashtra and Haryana victories are for Modi. It’s almost nearly as much a triumph for BJP president Amit Shah, a former (and controversial) home minister in Gujarat who led the BJP’s massively successful efforts in the national elections in Uttar Pradesh, the largest Indian state.

Though the BJP had hoped to win an outright majority in Maharashtra, it will nevertheless form the next government there, and it won nearly two times as many seats in the legislative assembly as its closest opponent, Shiv Sena. So while it could have been a wider blowout, it’s still a massively successful vote for the BJP, and it’s a considerable accomplishment for Shah (pictured above), who has become something akin to Modi’s 21st century Indian version of Mark Hanna (or, perhaps, Karl Rove).

It means that the BJP will build an even strong presence in the upper house of the Indian parliament, the Rajya Sabha (राज्य सभा), but it also gives the BJP control of one of the most important states in India — and a toehold in India’s south.

In Haryana, Manohar Lal Khattar, a 61-year-old Punjabi and first-time legislator has been selected as the BJP’s first-ever chief minister. A longtime Modi confidante, whose relationship with Khattar dates to the time when Modi served as the BJP national leader in charge of Haryana in the mid-1990s, Khattar leapfrogged more well-known possibilities.

In Maharashtra, Devendra Fadnavis, the BJP’s 44-year-old leader in Maharashtra, was the wide favorite to become the next chief minister going into the elections. A Nagpur native, however, Fadnavis favors statehood for Vidarbha, now the eastern-most and resource-rich region of Maharashtra.

Instead, Nitin Gadkari, currently minister for transport and rural development, and the BJP’s national president between 2010 and 2013, is emerging as the new frontrunner. As the public works minister in Maharashtra nearly two decades ago, Gadkari has a strong reputation for public infrastructure that he developed, especially in and around the Mumbai megapolis. Gadkari’s appointment would give Modi a steady ally and a high-profile figure from among the BJP’s new guard in one of the most vital state leadership positions in India.

2. Congress is losing its grip on India.

Prithviraj Chavan, who resigned late last month as Maharashtra’s chief minister when the NCP broke its decades-long alliance with Congress, will become the highest-profile casualty of the elections. A longtime confidant of the late Rajiv Gandhi, Chavan (pictured above) served as a minister under various national governments in the 1990s until his appointment as chief minister in 2010, when he replaced Ashok Chavan (no relation) following yet another corruption scandal.

His loss leaves Congress with just nine chief ministers throughout India, including just three of the 15 most populous Indian states, Karnataka, Kerala and Assam.

Barely five months after the worst national defeat in India’s post-independence history, Congress’s leaders, Sonia Gandhi and her son Rahul Gandhi, show no signs that they understand just how disillusioned that Indians became with the past decade of Congress-led governance, including corruption scandals on a massive scale and the sense that the Gandhis and former prime minister Manmohan Singh failed to unleash the full potential of India’s economy.

In Chavan’s defeat, Congress loses one of its party’s top figures, a chief minister with a reputation for honesty, and one of the few leaders with the potential base to challenge the Nehru-Gandhi family’s grip on the party’s (and India’s) politics. The most popular family member of all, Rahul’s younger sister Priyanka Vadra, is burdened by the shady deals and corruption accusations that haunted her husband, Robert Vadra, a Haryana-based businessman, who played a significant role in turning voters off from Congress.

Congress also loses a state that it had controlled for the past 15 years and a stronghold, in Mumbai, of much of its national support.

3. Shiv Sena should be very, very scared.

For decades, Shiv Sena has been among the BJP’s staunchest allies in Maharashtra.

That all changed over the course of the election campaign, when the BJP called the bluff of Shiv Sena leader Uddhav Thackeray (pictured above) when it decided to run separately — so much the better to contest as many seats as it wanted without deferring to Shiv Sena.

Founded in 1966 by political cartoonist Bal Thackeray, the party began as a Marathi nationalist movement to defend the rights of native Maharashtrians against the millions of Indians who moved in the first decades of India’s independence years to the Bombay metropolis. Over the years, its ideological background also incorporated the Hindutva values of the BJP as well, making the two parties natural allies over the past three decades. While many Indians worry about the Hindu nationalist nature of the BJP, Shiv Sena makes the BJP look moderate in contrast, and the closest Western political analog might be a far-right, ultranationalist party. Uddhav Thackeray took over the party in 2004, and he hoped that the 2014 elections would deliver to him the chief ministry. Shiv Sena first held the office between 1995 and 1999, when it governed with the BJP and, among other things, changed Bombay’s name to Mumbai.

This time, around, however, the dissolution of the BJP-Shiv Sena alliance and the NCP’s offer to support a BJP minority governments means that Shiv Sena has virtually no leverage and, contrary to long-held expectations, may not even form the government.

If Modi wants to telescope his ideological moderation, he might well take up the NCP on its offer, leaving Shiv Sena fuming in opposition. But Modi sneered that ‘NCP’ stood for ‘National Corrupt Party’ in the days leading to the vote, so allying with the NCP could dampen Modi’s credibility on corruption. So far, the BJP hasn’t made a decision, which means that it is taking seriously the idea of a more permanent break with Shiv Sena.

A permanent split That would also be bad news for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu nationalist civil society groups that fuels much of the BJP’s organic support (and that, some argue, exerts undue control over BJP governments.

4. The AAP’s momentum is gone, and India’s ‘third front’

of regional parties is on life support.

Though the NCP is making a possibly last-ditch effort to hold onto power in Maharashtra, it owes its leverage to Shiv Sena’s split with the BJP, not to any of its own inherent strength.

In Haryana, the Indian National Lok Dal (INLD), had one of the worst showings in its history, losing 12 of its seats, in part due to the corruption convictions and jail sentences last year for two of its leaders, former chief minister Om Prakash Chautala and Ajay Chautala, both sons of the party’s founder, Chaudhary Devi Lal. Om Prakash, the party’s chief ministerial candidate, ridiculously pledged to take the ministerial oath from prison.

To the extent that the NCP and the INLD lost steam in the face of the Modi juggernaut, it bodes ominously for other regional third parties, including in India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh, where the BJP nearly swept the state in the national elections earlier this year, in the left-leaning West Bengal and in Bihar, which will conduct regional elections next year.

That’s especially true after the breathtaking dismissal of Tamil Nadu’s chief minister Jayalalithaa after her own corruption conviction last month, and it could augur additional breakthroughs for the BJP in the next round of state elections in Jharkhand and in the contested Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir.

But it’s worst of all for the AAP, whose leader Arvind Kejriwal (pictured above) rode a wave of popular discontent to national acclaim in the Delhi Capital Territory’s December 2013 elections. After serving just 49 days as chief minister, however, Kejriwal resigned in a huff after failing to pass a landmark anti-corruption bill. He doubled down on political miscalculation when he tried to contest national elections, spreading the new party’s resources too thin and winning just four seats nationally (none of them in Delhi).

The AAP’s failure to contest the local elections in Haryana just six months later seems equally baffling, considering that the state should be fairly hospitable to Kejriwal, who was born in Haryana, a state that encircles nearly all of western Delhi, where its clean-government appeal is still strong. The AAP’s reticence could embolden the BJP to try to form a new minority government in Delhi (which has been under ‘president’s rule’ since the fall of Kejriwal’s government) or even push for snap elections that the BJP would almost certainly win.