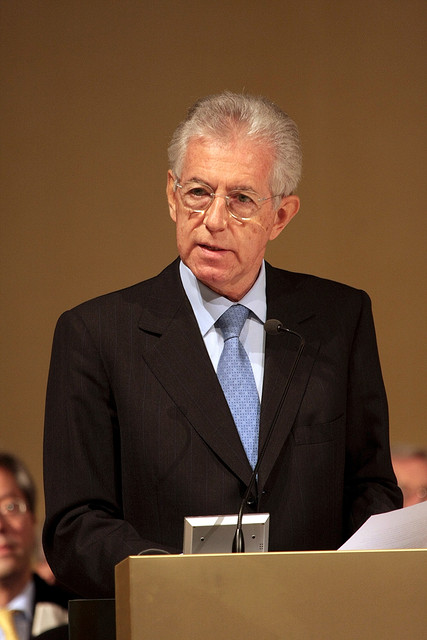

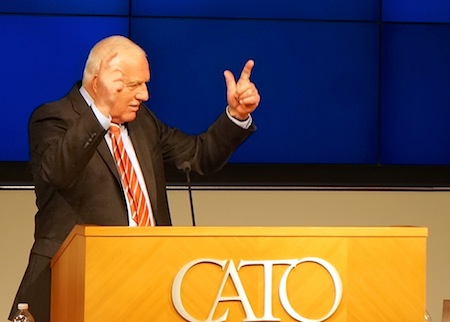

Just three days after leaving the Czech presidency, Václav Klaus spoke at the Cato Institute in Washington earlier today — Klaus is joining Cato as a senior distinguished fellow this spring.![]()

![]()

Klaus, who stepped down after a decade in office, didn’t break much new ground — his remarks were essentially everything you’d expect from the famously euroskpetic former president, who was the last European Union head of state to sign the Treaty of Lisbon (and quite reluctantly, at that).

The great eurozone fight

In brief, Klaus has long argued that the eurozone is not an optimal currency zone, it’s a project that was implemented without sufficient democratic input from everyday Europeans, and the economic costs of monetary integration and centralization far outweigh the benefits, and those costs have become increasingly evident from the economic pain suffered today in Greece, Spain, Italy and throughout Europe.

Klaus’s diagnosis has become fairly uncontroversial — both on the left and the right, and for both intergovernmentalists and neo-functionalists alike. A lot of European federalists would agree that the European Union needs more robust democratic institutions at the supranational level. Many economists agree that the one-size-fits-all monetary policy has been incredibly harmful to many countries in southern Europe since 2008, and the painful internal devaluation forced upon many countries in the European periphery, from Latvia to Greece, has been a needless exercise in poor economic policymaking.

But whereas many economists would argue that the solution lies in greater fiscal harmony (especially through fiscal transfers from wealthier regions to poorer regions), looser monetary policy, a eurozone-wide borrowing capacity, debt forgiveness and a doubling-down on the more long-standing commitment to the free movement of goods, services and people throughout the European Union, Klaus’s solution is to unwind the eurozone.

Klaus would rather see a way for Greece — and other troubled economies — to simply exit from a eurozone that’s delivered now nearly half a decade of GDP contraction, painful downward pressure on income, and widespread unemployment and social rupture.

That’s not a crazy idea economically — if Greece could leave the eurozone tomorrow (or if Greece simply went bankrupt, thereby essentially forcing Greece out of the eurozone), it could conceivably pursue a much more aggressive monetary policy, devalue its currency, and take other steps to make its exports more competitive in global markets once it’s no longer yoked to a monetary policy that’s better suited for, say, the German economy.

But that’s not the entire story. Greece might also suffer extraordinarily in the short-run while it makes that transition — starting with how it would reintroduce the drachma and how it would even finance basic governance outside the current eurozone regime, forcing perhaps even more austere budget-cutting in a country where the social safety net is already tattered.

And those are just the problems inside Greece — though the Greek economy is just a fraction of the European economy, it could set off a chain reaction of fear, bank runs and deep recession throughout the eurozone as investors pull out of not only the peripheral economies, but also out of the entire eurozone. How would a massive Greek devaluation affect Cyprus? Would Spain and Italy withstand the inevitable bank runs and currency flight? The chain reaction of unraveling one of the world’s foremost reserve currencies could well be catastrophic.

Looking to national parallels: the Czechoslovak breakup and German reunification

Klaus related the current monetary union to the breakup 20 years ago of Czechoslovakia into two separate nations — a process that Klaus said was painful though necessary (though the Slovak economy is doing much better these days than the Czech economy). But Greeks might be troubled by the more painful example of the breakup of the Yugoslav federation and the Soviet Union, both of which were also monetary unions as well as political unions. The breakup of the ‘ruble zone’ led to massive hyperinflation throughout the Soviet Union and an economic shock that cut standard of living in half. There’s simply no way to know what forces could be unleashed by the process — no matter what anyone says, there’s not a precedent for unraveling even a tiny part of the world’s largest currency union in an orderly fashion.

I would have liked to hear, in particular, Klaus’s thoughts on another contemporary experiment in currency union: German reunification.

Continue reading Václav Klaus, fresh from Czech presidency, discusses eurozone in Washington