Since the initial June parliamentary elections in Turkey, the country has weathered more instability than at any other period since the Islamist Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) came to power.![]()

On the eve of fresh elections this weekend, consider all that’s happened since the June elections when the AKP lost its parliamentary majority:

- Coalition talks failed between prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and the two secular opposition parties that were most likely to support an AKP-led government.

- Since 2011, the value of the lira has fallen by 50% against the U.S. dollar and Turkey’s once galloping economic development is slowing — to just a projected 3.2% in 2015.

- A suicide bombing on July 20 in the southern city of Suruç killed 33 people. In response, Kurdish forces attacked Turkish police after Turkish officials downplayed the need to secure areas of southeastern Turkey that are most heavily populated by the Kurdish minority.

- Turkish forces responded to the Suruç attack by joining the military effort against ISIS/Islamic State/Daesh, the Sunni radical group that has extended its ‘caliphate’ across eastern Syria and western Iraq.

- Turkish forces also used the Suruç attack to wage a much more aggressive attack against the militant Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, Kurdistan Workers’ Party), escalating a conflict that had previously been working its way toward a peaceful settlement between Turkey’s government and the PKK’s jailed leader, Abdullah Öcalan.

- Another suicide bombing on October 10 in the Turkish capital of Ankara at a peace rally became the deadliest terrorist attack in modern Turkish history, further polarizing Turkish voters who alternative pointed fingers at ISIS, the government and the PKK.

- Critical media voices have been harassed or prosecuted by a government whose record on press freedom was already deteriorating.

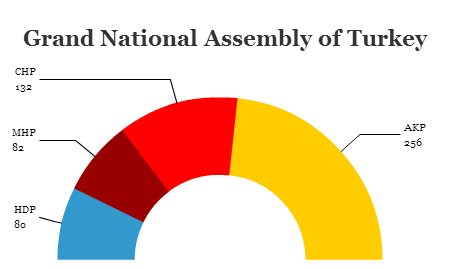

In the June elections, the AKP won just 256 seats in the Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (Grand National Assembly), 20 short of a majority. It was the first time since the AKP first came to power in the 2002 elections that it failed to win a majority, scuttling Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s to consolidate power in the Turkish presidency after won Turkey’s first-ever direct election to the mostly ceremonial office last summer.

The AKP fell so low because, for the first time in Turkish history, a pro-Kurdish party, the leftist Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP, People’s Democratic Party), ran for election on a unified list and won enough support to meet the 10% electoral hurdle for winning seats in the National Assembly. With the HDP taking 80 seats, it made it that much more difficult for the AKP to reach an absolute majority.

The problem is that polls show Turkish voters will roughly vote in the same proportions as they did in June, despite the tumult of the ensuing five months. It doesn’t take too much skepticism to see that by escalating tensions and instability in the Kurdish-dominant southeast, Erdoğan might have hoped to scare some voters back to the AKP or otherwise make polling conditions so unsafe that the HDP vote falls below 10%, though there’s not been a single major poll since June that shows the HDP with less than 10%.

*****

RELATED: How the AKP hopes to regain

its absolute majority in November

*****

If, somehow, fairly or not, Erdoğan and his allies manage to keep the HDP below 10%, he will almost certainly win the majority he is seeking. But it will come at a huge cost. After a decade of gradually lifting restrictions on the Kurdish language and culture and after working so hard to bring about a ceasefire between the Turkish military and the PKK, Erdoğan will have shown that he’s willing to rubbish his legacy and the rights of a minority group to cling to power. The lesson for Turkey’s Kurds might easily be that there’s no future in working through the democratic process; instead of embracing the HDP’s peaceful, democratic approach, Kurds could once again turn to the PKK’s more radical militant approach. Just months ago, however, such an outcome seemed fanciful, given the popularity of the HDP’s charismatic leader, attorney Selahattin Demirtaş.

But if the polls are correct, and the November 1 election is just as inconclusive as the June 7 election, Turkish analysts are already speculating that the country could face a third election sometime next spring, the idea being that Erdoğan will force Turks to keep voting until they get it right.

A NATO partner and, at one time, a potential future member of the European Union, Turkey plays a vital strategic role in the Middle East as Syria’s civil war rages into its fourth year. From the U.S. perspective, Turkey’s military assistance is vital to checking ISIS. With U.S. special forces set to arrive in Syria, and with Russian forces now working to bolster Syrian president Bashar al-Assad against all anti-regime rebels (ISIS and otherwise), U.S. officials want Ankara to work with the Kurdish peshmerga forces that are opposing ISIS in both Iraq and Syria. Meanwhile, European officials, including German chancellor Angela Merkel, want Turkey’s cooperation in processing the wave of refugees from Syria and Iraq that have settled by the millions in Turkey as more increasingly push onward to the European Union, causing the biggest wave of human migration in Europe since World War II.

At a time when Turkey’s regional and global role is so vital to so many world powers, Erdoğan’s cavalier approach to internal stability is already having devastating side effects. If no party wins a majority on Sunday, and coalition talks fail yet again (a likely prospect), no one knows just how far Erdoğan would be willing to go to shake up domestic politics. But a prolonged period of further political uncertainty could signal more restrictions on political and individual freedoms, pullback by international investors in the Turkish economy, a more autocratic approach from Erdoğan and, above all, additional escalation between Turkish forces and the PKK — none of which bodes well for Turkey at such a crucial point.