It’s clear that things are looking up for the bilateral relationship between Russia and Turkey.![]()

![]()

At the beginning of last December, the two countries locked into a troubling standoff after Turkey shot down a Russian airplane that had repeatedly crossed into Turkish airspace. The diplomatic standoff came at a time when Russian president Vladimir Putin was using Russian military force to boost the efforts of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad to push back Sunni rebel forces. In response, Putin slammed trade restrictions against Turkey.

A lot can happen, however, in nine months, and yesterday, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan traveled to Moscow to mend somewhat broken relations with Putin, who announced that the country would slowly lift economic sanctions against Turkey on the path to restoring normalized relations.

Erdoğan, last month survived a coup attempt from within elements of the Turkish military that, for a few hours at least, seemed like it had some chances of success. The first world leader to call Erdoğan to pledge his support?

Putin.

With Erdoğan placing blame for the coup on the shoulders of Fethullah Gülen (who lives in exile in Pennsylvania) and his Gulenist followers in Turkey, the crackdown has been swift and deep. In the past four weeks, Erdoğan has purged many Turkish institutions of tens of thousands of officials suspected of having any ties to Gulenism. That includes the military and the police forces, but also over 20,000 private school teachers, 10,000 education officials and agents within other government ministries. Erdoğan has also ordered the shutdown of around 100 media outlets, which echoes a decision earlier in March to seize Zaman, one of Turkey’s most popular independent newspapers.

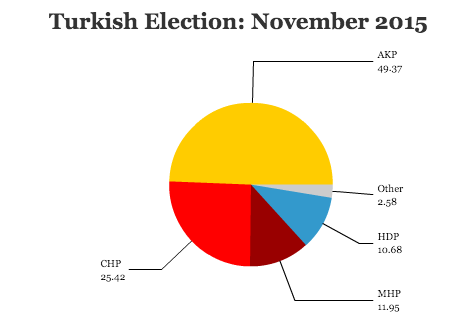

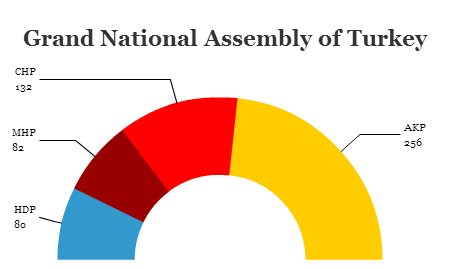

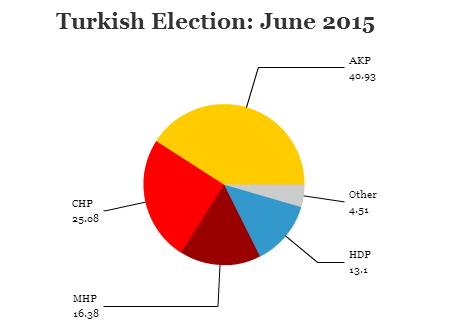

Last May, prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu resigned after a series of files (the so-called ‘Pelican Files’) were released to the public and that showed the former foreign minister, who led the governing Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) to a minority victory in June 2015 and a majority victory in November 2015, was increasingly uncomfortable with Erdoğan. His misgivings included both the push to concentrate power within the Turkish presidency (following Erdoğan’s shift from prime minister to president in 2014) and with the increasingly militant approach to Turkey’s Kurdish population — after over a decade of progress for Kurdish minority rights and a detente with the PKK, a militant, communist Kurdish militia.

Binali Yıldırım, the new prime minister, formerly a transport, maritime and communications minister and a loyal Erdoğan supporter, has been far more willing to countenance the shift from a powerful parliamentary government to a presidential one.

It has been clear since the late 2000s that Erdoğan was not the pure democrat that his supporters (and many sympathizers in the United States and Europe) once believed, and it’s been clear since the Gezi Park protests in 2013 that Erdoğan has no respect for the kind of liberal freedoms — expression, assembly, press, speech and otherwise — that are so important to a functioning democracy. In the wake of the July coup attempt, Erdoğan’s instinct towards the authoritarian has only sharpened. (Though, to be fair, imagine the kind of response that would follow from an American president if a military coup managed to shut down New York’s major airports, take control of public television and bomb the US Capitol).

That his first post-coup visit abroad was to Russia to visit Putin will, of course, be a source of increasing anxiety among US and European officials, who need Erdoğan’s assistance on at least two fronts: first, stemming the flow of migrants from Syria that cross through Turkey en route to Europe and, second, facilitating US, European and NATO efforts to weaken and ultimately displace ISIS from their territorial berth in eastern Syria and western Iraq. Continue reading Why Erdoğan is not — and will never be — Putin