There will be plenty of time to think about the next Italian general election if, as is likely, current prime minister Mario Monti is permitted to carry on with his technocratic government until April 2013, the last date upon which the next general election must be held.

It’s worth taking in two important stories from last week:

The Economist points us to reports in the Italian press that Silvio Berlusconi (pictured above, right), the éminence grise (well, surprisingly jet black) of Italian politics since about 1994, is likely to lead the center-right in the upcoming election and is taking an increasingly critical position against Monti’s government.

Italy’s federal government, a technocratic government formed under Monti, an economist and former European Commissioner, with a mandate to reform Italy’s sclerotic economy and shrink its bloated public sector — with the support of Berlusconi’s own center-right Il Popolo della Libertà (PdL, the People of Liberty) and the main opposition center-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party), has managed to keep a skittish bond market at bay, which has been spared, for now, the same fate as Spain in the bond market last week.

Meanwhile,

The New York Times last week

showcased the fiscal problems of Sicily, which is tottering further on the edge of a debt crisis than Italy itself. Monti’s government recently sent €400 million to Sicily to forestall a potential default by a region that has long been plagued by low growth, outsized government patronage and abuse of its considerably autonomous power — to say nothing of the Mafia corruption issue.

Today, in fact, Sicily’s regional president, Rafaelle Lombardo resigned following an indictment for corruption — elections follow for October 28 and 29 of this year.

Since November 2011, when Berlusconi stepped down, more or less in disgrace, he has kept a fairly low profile.

But everyone knows as long as he’s around, he would have been the chief behind-the-scenes power of Italy’s center-right. So when he seemed to designate a successor in November in former justice minister, Angelico Alfano (pictured above, left), now the secretary of Berlusconi’s PdL, it seemed difficult to believe that Il Cavaliere, as Berlusconi is known in the Italian press, was really stepping aside.

Alfano, who is Sicilian, has not managed to recover any ground for the PdL (formerly — and potentially again in the future — known as Forza Italia) — one poll from SpinCon released on July 19 shows the PdL winning just 18% of the vote to 27% for the Democratic Party and 14% for the newly formed Euroskeptic and populist party of comic and blogger Beppe Grillo, the Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement).**

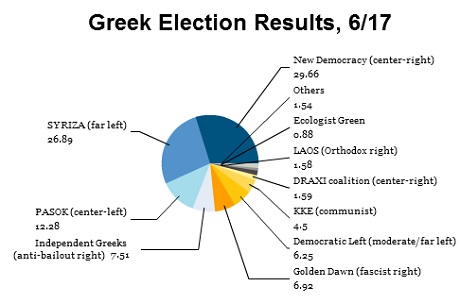

Italian politics have long been fragmented, but like Greece earlier this year, Italian voters seem to be fragmenting even further under the weight of austerity measures introduced by Monti’s government. Monti himself has said he will not run for election in his own right under any banner.

But above all, Berlusconi’s ace is that he still has more media power than anyone else in Italy. He also remains the most charismatic leader among a political class of bores — for instance, has anyone outside of Italy even heard of Pier Luigi Bersani, the main center-left opposition leader?

Berlusconi practically invented Italian television in the 1980s by buying TV stations across Italy and harmonizing their content at a time when RAI (Italy’s public television network) was supposed to hold a monopoly on national stations. He still holds an incalculable political advantage because of that power — it’s what helped him burst onto the political scene in 1994 and what helped him keep power in much of the 2000s, even through the last days of sordid accusations of his cavorting with underage girls and prostitutes at ‘bunga, bunga’ parties.

It’s not clear that Italian voters are willing to turn back to those days (a strong majority of voters say they refuse to back Berlusconi ever again), but if anyone can pull it off, it’s Berlusconi.

Also, for a premier who spent a significant amount of legislative time in the 2000s crafting immunity bills to protect himself from prosecution relating to all sorts of seamy dealings, Berlusconi is likely tempted by the shield from prosecution that yet another stint in office would bring — or at least tempted by the opportunity to parlay a political comeback into a term as Italy’s president in the future.

And at age 75, Berlusconi is a fairly young man by the standards of Italian institutions; Alfano was born in 1970. Italy is a country of old men — to have a forty-something prime minister is unheard of. (Recall that the 93-year-old Giulio Andreotti, a former prime minister in the 1970s and 1980s, now an Italian ‘senator for life’, was instrumental in bringing down the short-lived leftist government of Romano Prodi just six years ago.)

But Alfano’s Sicilian heritage raised an eyebrow in November and it does so especially now, with Sicily’s finances in the headlines and yet another Sicilian president resigned under ties to the omni-present curse of Mafia infiltration.

It’s worth remembering that “Italy” as a national concept really only emerged in the 1860s — and even today, just over 150 years after “unification,” it’s hard to think of Italy as a true country, even if you don’t believe that nationhood in Italy is really a myth-laden fluke. You have to go back to the mid-1950s to find a Sicilian who has served as Italy’s prime minister — Mario Scelba. No Sicilians have served as president of Italy in the current republic. No Sicilians have served as president of Italy in the current republic. That may not be so surprising, given that Sicily is so far away, not just geographically, but culturally from Rome, to say nothing of Milan or Florence or Turin. Although Sicilian votes essentially enshrined Italy’s old Christian Democrats in power until the 1992 Tangentopoli (‘Bribesville’) scandal that, in effect, wiped clean Italy’s political slate, Sicilians have rarely held the highest office in Italian politics.

So with Sicily’s finances and its corruption in global headlines, the “Sicily question” is yet another for Berlusconi to sideline Alfano as the 2013 elections approach — for the time being, at least.

![]()