India, with 1.24 billion people, is the world’s largest democracy. ![]()

That makes its upcoming election, which will be conducted in nine phases between April 7 and May 12, the most ambitious election in world history.

* * * * *

RELATED: Here’s a map and chart of the state-by-state breakdown of each of the nine phases.

* * * * *

India this spring will elect the Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the House of the People, the lower house of India’s parliament. Though it currently has 545 members, the actual number of MPs may vary, so the Lok Sabha can have up to 552 members. Legislators are elected on a first-past-the-post basis in single-member districts. Larger states have more representatives than smaller states (from just a single seat for the smallest territories to a high of 80 seats from Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state).

Officials will announce the national results on May 16.

The Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) is seeking a third consecutive term in power. Manmohan Singh is stepping down as prime minister after ten years, regardless of his party wins the election. Rahul Gandhi (pictured above), the latest member of the Nehru-Gandhi family to vie for the premiership, is leading the campaign along with his mother, Sonia Gandhi, who has been Congress’s leader since 1998.

Congress, with 206 seats in the Lok Sabha, leads the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), which, with 226 seats, forms the current government coalition. Though the Congress has always dominated the UPA, defections over the term of the last five years have transformed it into a decimated coalition that comprises just Congress and a handful of small regional parties.

Polls, however, show the conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) will widely outperform Congress, partly due to dissatisfaction with India’s stalled economy and a decade of corruption and massive scandals. But part of its allure is undeniably the BJP’s formidable prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi, since 2001 the chief minister of Gujarat. Modi (pictured above) promises to deliver to the entire country that kind of strong economic growth and development that Gujarat currently enjoys.

He’s not without controversy, however, given his government’s murky role in a series of riots in 2002 that left over 1,000 Muslims dead in the worst domestic religious violence of the decade. Modi has never been formally implicated in the riots, but his critics believe his government, at the very least, did too little to stop the violence. Though Modi last December spoke of the pain and anguish that the riots caused, he has yet to offer a formal apology for his government’s conduct at the time.

The BJP currently holds just 117 seats in the Lok Sabha, and it is the leading member of the opposition coalition, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). Like the UPA, however, defections have left the NDA reduced to essentially the BJP, a few regional parties and the ultranationalist Shiv Sena (SS, शिवसेना), which lies on the hard right of India’s Hindu nationalist spectrum, and which has a strong base in Maharashtra state (2nd most populous state).

If the most recent state elections are any guide, the BJP certainly seems well poised for victory. In December 2013, the party retained its hold on Madhya Pradesh (6th most populous state) and Chhattisgarh, and it picked up control of Rajasthan (8th most populous state). Modi won a third term in Gujarat (10th most populous state) in December 2012 in a landslide. The only outlier is Karnataka (9th most populous state), where the BJP lost its sole foothold in India’s south, though the loss was largely due to state-level scandal and splintering within the local party.

Although polls forecast a strong BJP victory, polls have been wrong in the past (most recently in 2004, when Congress won an upset victory over the incumbent BJP government). Furthermore, regional fragmentation of Indian politics has made it difficult for one party to win an outright majority — that’s especially true for the BJP, which has a difficult time winning voters outside northern India’s ‘Hindu belt.’

That means that the BJP, even with its allies, could emerge as the strongest party in the Lok Sabha, but nonetheless short of an absolute majority. That will depend on the appeal of regional parties throughout India as much as the respective Congress and BJP campaigns.

In Uttar Pradesh, for example, the election will be at least a four-way race, with the BJP and Congress competing against the Samajwadi Party (समाजवादी पार्टी, Socialist Party), which has led the regional government since 2012, and the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP, बहुजन समाज पार्टी), which formerly led the regional government in the late 2000s. Given that the state holds nearly one-third of the seats it needs to form a majority in the Lok Sabha, the BJP hopes to make a breakthrough performance in the state. Modi himself is running in the Varanasi constituency in Uttar Pradesh, highlighting the BJP’s campaign in what is considered India’s holiest and most spiritual city (formerly known as Benares) on the banks of the Ganges River.

In West Bengal (4th most populous state), the center-left All India Trinamool Congress (সর্বভারতীয় তৃণমূল কংগ্রেস) and the communist Left Front (বাম ফ্রন্ট) are likely to win most of the seats. In Tamil Nadu (7th most populous state), the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK, the All India Anna Dravidian Progress Federation) holds a similar lock on voters.

Many regional parties, including the SP and AIADMK, are joining a leftist ‘Third Front’ that also includes the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM, भारत की कम्युनिस्ट पार्टी (मार्क्सवादी)). The Third Front will also feature the largest party in Bihar (3rd most populous state), the Janata Dal (United) (JD(U), जनता दल (यूनाइटेड)) of chief minister Nitish Kumar. Though the JD(U) was previously the second-largest party in the BJP-dominated coalition, Kumar pulled out in June 2013 in protest of the BJP’s decision to name Modi as its prime ministerial candidate, on the basis of his association with the 2002 anti-Muslim riots.

Though India’s leftists have been trying for a quarter-century to form a truly competitive united left front, 2014 doesn’t seem like it will be their year, partly due to the hasty formation of the Third Front and the perception that the parties are only loosely allied.

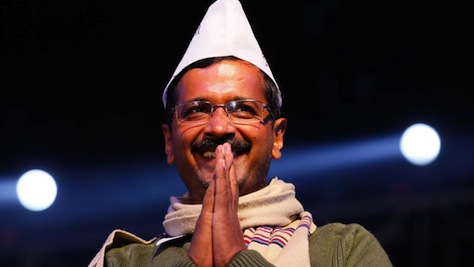

A much more powerful force is Arvind Kejriwal, whose Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी, Common Man Party) led a 49-day government in Delhi after riding an anti-corruption campaign to success in last December’s regional elections in the National Capital Territory. Kejriwal resigned in February when it became clear that his government would not have enough support to pass the AAP’s priority, a ‘jan lokpal’ (citizen’s ombudsman) bill to facilitate anti-corruption efforts.

Now freed to campaign nationally, Kejriwal (pictured above) hopes to attract voters with his message of good government who are both disenchanted by Congress and wary of Modi and the BJP. Outside Delhi, however, it may be a difficult battle for a party that was formed only in November 2012.

Though ideology plays a role in Indian politics, it’s not nearly as strong as in European and North American politics. So while Congress is, generally speaking, a center-left party, and the BJP leans to the right, those generalizations aren’t always accurate. For instance, it was Congress that implemented the most neoliberal reforms in India’s history. Singh’s more recent attempts for further reform have not only met resistance from within his own party, but also from protectionist interests within the BJP as well.

Religion naturally plays an important role in politics. Some of the BJP’s strength lies in its appeal to hardcore Hindu nationalists. Indian Muslims, as a general rule, mostly support Congress. In Punjab, the Shiromani Akali Dal (ਸ਼੍ਰੋਮਣੀ ਅਕਾਲੀ ਦਲ) dominates state politics as a religion-based party that represents the interests of Sikhism.

More complex are the ways in which class, caste and politics intersect. The consequences of India’s caste system, both historically and as it affects Indian life today, can be difficult to grasp. Traditionally, however, the four major castes, which includes Brahmins at the top of the caste hierarchy, governed not only occupation and marriage, but important political ties as well. Indians outside the caste system, including dalits (formerly untouchables) and aboriginal groups in India, have faced even greater social stigma and political and economic exclusion. Today, however, dalits form a powerful political bloc, and some parties, such as the BSP in Uttar Pradesh, came into existence to advance dalit interests. The BSP’s leader, Mayawati, formerly the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, has been touted as India’s first potential dalit prime minister.

India’s constitution includes protections for all of these groups, which are classified under Indian law as Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Classes (OBC). Though the BJP has not historically performed well among lower castes and dalits, Modi himself belongs to an OBC. If he becomes prime minister, he will be the first OBC prime minister in India’s history.

* * * * *

Though the Indian National Congress has traditionally been the most dominant force in national politics since before Indian independence in 1947, it could have its worst-ever showing in 2014.

The party was formed in 1885, as a vehicle for promoting Indian participation in what was then British colonial governance. But Congress quickly and enthusiastically embraced the cause of Indian independence in the first decades of the 20th century. Congress’s leaders, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, became the chief figures in the fight for Indian independence in the 1920s through the 1940s.

After independence in 1947, which coincided with the Partition of British colonial India into a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan, Nehru served as India’s first prime minister. Until his death in 1964, Congress overwhelmingly dominated Indian government. Nehru oversaw the promulgation of the 1950 Indian constitution, which created a British-style parliamentary system with American-style separation of powers and a strong central government. Nehru also oversaw the reorganization of India’s states on the basis of language in the late 1950s. India retained many features of British colonial governance, including a strong civil bureaucracy. Nehru and Congress adhered to an official policy of panchasheela, or non-alignment, in international affairs, but India during the Cold War was always closer to the Soviet Union than to the United States, and Indian economic policy heavily featured state planning.

Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi (pictured together above) became India’s prime minister in 1966, establishing a dynastic trend in Congress and in Indian politics that continues to this day. (Note that Indira’s husband, Feroze Gandhi, was not related to the more famous Gandhi). Indira Gandhi’s tenure was markedly rockier, however, as Congress’s lock on Indian electoral politics started to crumble. In 1965, India fought a war against Pakistan over Kashmir, a Muslim-majority state in northern India that, to this day, Pakistan claims as its own. The Kashmir issue remains the chief impediment to normalized Indian-Pakistani relations. In 1971, India found itself embroiled once again in a war against Pakistan, this time resulting from East Pakistan’s decision to declare independence as the sovereign country of Bangladesh.

Indira Gandhi inadvertently boosted the rise of political opposition to Congress by invoking a constitutional provision allowing for ’emergency rule’ between 1975 and 1977, which amounted to the suspension of normal democratic and liberal freedoms. Widely seen as an authoritarian and politically motivated attempt to maintain Congress’s grip on government, Congress lost power for the first time in the 1977 elections, when the Janata Party (जनता पार्टी, the People’s Party) formed as a broad-based anti-Congress coalition of socialists, Hindu nationalists and other movements. Though Morarji Desai became India’s first prime minister from outside Congress, his coalition eventually crumbled over policy and other differences, and Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980.

Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi family continued to govern India throughout the rest of the decade, but not without heavy personal costs. In 1984, after the government stormed the Golden Temple of Amritsar to remove Sikh terrorists, two of Indira Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards assassinated her. Her son, Rajiv Gandhi, succeeded her as prime minister, though he too was assassinated in 1991 by a Tamil suicide bomber.

During the 1990s, prime minister P.V. Nasrashima Rao broke both the Nehru-Gandhi hold on power in Congress and the statist orientation of what India’s economy, which had become incredibly sluggish and uncompetitive in the post-Soviet, connected world economy. Between 1991 and 1996, Rao and his finance minister Manmohan Singh introduced a series of reforms that liberalized much of India’s economy and facilitated India’s participation in global markets. The Rao-Singh reforms of the early 1990s are one reason for India’s spectacular growth in the 2000s, an influx of foreign direct investment and the rise of its IT and service sectors.

Meanwhile, by the 1990s, the BJP emerged as the strongest opposition party in Indian politics. It first won power, briefly, in 1996, but the first sustained BJP government began in 1999 under Atar Behari Vajpayee. Unlike Congress, which as the party of Indian independence and governance for so many decades, adopted a secular ideology, the BJP’s roots lie in the movement to incorporate hindutva, Hindu values, more overtly into Indian government.

Although the vast majority of Indians (80.5%) are Hindu, the country’s massive population means that even a small religious minority includes tens of millions of Indians. So while just 13.4% of all Indians are Muslim, that amounts to over 176 million Muslims in the entire country. India also has a significant number of Christians (2.3%) and Sikhs (1.9%), and in the state of Punjab, Sikhs form a majority. Religious conflict in India has, at times, ripped at the fabric of India’s post-independence secular state. In 1992, a riot in Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, led to the destruction of the 16th-century Babri Mosque. Riots between Muslims and Hindus left over 2,000 people dead amid reprisals and counter-reprisals on both sides. Vajpayee had distanced himself from the Ayodhya controversy, however, and upon taking, his BJP government focused more on national security and economic policy than on promoting Hindu culture.

Under Vajpayee, both India and Pakistan became nuclear powers, though they clashed yet again in 1999 over Kashmir. In 2004, the BJP ran for reelection on the slogan of ‘India Shining,’ and its leaders campaigned on the gains of India’s rapidly growing economy. Congress, emphasizing policies to benefit the majority of Indians who had not felt the benefits of economic growth, won an upset victory under the leadership of Sonia Gandhi.

Although the Indian constitution didn’t ban the Italian-born Gandhi from become prime minister herself, she avoided what would have been a controversial decision by ruling herself out of contention for the post, instead guiding government from her position as Congress party leader. Singh (pictured above), the former finance minister, became India’s first Sikh prime minister. In his first term, Singh presided over a rapidly growing Indian economy, signed a high-profile nuclear agreement with the United States, and led India through the aftermath of the November 2008 Pakistani terrorist assault on Mumbai, a series of bomb and gun attacks that killed almost 200 people.

Congress won reelection in 2009, due as much to India’s strong economy as to the lackluster leadership of the BJP. Singh’s second term as prime minister has been considerably rougher. Though Singh enacted reforms to liberalize India’s retail sector in 2013, the efforts pale in contrast to the market reforms of the early 1990s. While GDP growth rose in 2013, it fell from 10.5% in 2010 to 6.3% in 2011 to just 3.2% in 2012.

Singh’s government in 2011 was implicated in the 2G telecom spectrum scandal, which may have lost up to $7 billion — officials accepted bribes from mobile telephone companies in exchange for undercharging them for spectrum licenses. Though Singh has a personally strong reputation as an honest public servant, the 2G scandal is just the most sensational of a dozen or more cases calling into question the integrity of many senior ministers within Congress.

Despite the gains of the past two decades, 32.7% of all Indians live on less than the equivalent of $1.25 a day (the international standard for poverty), and 68.7% live on less than $2 per day. India’s literacy rate, as of 2011, was just 74%, and the youth literacy rate just 82%.

The difficulties haven’t been solely economic, though. After a sensational gang rape and killing of a female student in December 2012 in Delhi, the government passed a new anti-rape criminal statute into law, though critics argue that it doesn’t go far enough to protect women and punish convicted rapists.

Notwithstanding the hopes of Pakistan’s prime minister Nawaz Sharif to build better relations, Indian-Pakistani relations remain incredibly strained in the wake of the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

* * * * *

See below all of Suffragio‘s coverage of India’s 2014 election and other coverage of Indian national and regional politics:

Photo of the day: Modi, Sharif meet at India’s inauguration

May 26, 2014

A state-by-state overview of India’s election results

May 19, 2014

India’s election results: Modi wave largest mandate since 1984

May 16, 2014

The phenomenon of Narendra Modi — 56-inch chest and all

May 16, 2014

Who’s who in Modi-world: A guide to the next Indian government

May 15, 2014

The National Interest: Pivoting to Modi: US-India relations in the Modi era

May 15, 2014

Indian court ruling highlights women’s issues in election campaign

May 13, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 9

May 12, 2014

Mamata-Modi spat takes center stage in West Bengal

May 12, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 8

May 7, 2014

How the 2002 Gujarat riots became so important to the 2014 election

May 6, 2014

Telangana, India’s newest state, votes to determine its first government

April 30, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 7

April 30, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 6

April 23, 2014

Jayalalithaa, Tamil actress-turned-strongwoman, could play India’s kingmaker

April 23, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 5

April 17, 2014

India’s Mr. Clean seeks fourth term in Odisha elections

April 17, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 4

April 11, 2014

Chamling hopes to break record as India’s longest-serving chief minister

April 11, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phase 3

April 10, 2014

Did Kejriwal err in resigning position as Delhi’s chief minister?

April 10, 2014

Indian Lok Sabha elections: Phases 1 and 2

April 9, 2014

Could LK Advani become India’s next prime minister?

April 8, 2014

The path to India’s next government runs through Uttar Pradesh

April 3, 2014

US ambassador to India resigns a week before Indian elections

April 1, 2014

What exactly is the Gujarat model — and can Modi export it nationally?

March 26, 2014

What does Nitish Kumar want?

March 24, 2014

Is Priyanka Vadra the secret Gandhi family weapon for Congress?

January 24, 2014

Meet Arvind Kejriwal — the rising anti-corruption star of Indian politics

January 10, 2014

Is there a potential parliamentary path to amending Section 377 in India?

December 12, 2013

India’s supreme court re-criminalizes same-sex conduct in LGBT setback

December 11, 2013

Anti-incumbent momentum rises with BJP gains in northern Indian regional elections

December 9, 2013

Raghuram Rajan’s vision of the future of the Indian economy

October 10, 2013

Sharif, Singh meet in New York, agree to cooperate over terror attacks

September 30, 2013

Forget Obama-Rowhani. This weekend’s about the Singh-Sharif meeting.

September 28, 2013

Raghuram Rajan’s selection as India’s new central bank governor is good news for Modi

August 9, 2013

Do Chinese-Indian relations explain the result of the Bhutanese elections?

July 15, 2013

BJP’s Modi begins Indian election campaign in an incredibly strong position

June 25, 2013

In one year, South Asia and the Af-Pak theater as we know it will be transformed

May 28, 2013

As expected, BJP loses Karnataka state elections to surging Congress

May 8, 2013

Karnataka, India’s high-growth power state, votes in shadow of 2014 national campaign

May 2, 2013

Modi’s Gujarat victory sets platform for national ambitions in 2014

December 12, 2012

Gujarati voters consider third decade of BJP rule as Modi looks to prime minister race in 2014

December 10, 2012

Could Coalgate final bring down Manmohan Singh’s government in India?

August 27, 2012

Indian blackout a metaphor for India’s political, economic and infrastructure growing pains

August 1, 2012

Modi photo credit to PTI.

Rahul Gandhi photo credit to INC.

Kejriwal photo credit to Getty Images.

Singh photo credit to PardaPhash.

All other photos credit to World Bank / Curt Carnemark.

Great post ! the facts and analysis is spot on I must say. I do believe that current government of India has sparked unwanted issue of extremism. Manmohan Singh was a visionary and he developed India economically and socially so much!!