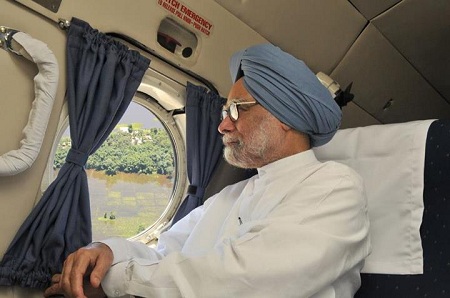

In the span of 10 days, India has seen a government report on government abuse in awarding coal contracts morph into perhaps the most ferocious scandal of Manmohan Singh’s government.![]()

The scandal — known as ‘Coalgate’ — stems from an August 17 report from the Comptroller and Auditor General of India that accuses the governing Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) of handing out coal mining contracts to companies without going through the proper competitive bidding process, leading to inflated prices for the ultimate recipients. The accusation comes.

Singh spoke about the scandal for the first time on Monday in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s parliament, challenging the house to debate the issue in full and disputing the corruption accusations. In turn, Singh was met with jeers and shouts of, “Quit prime minister!”

His remarks appear to have emboldened the opposition — the conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, or भारतीय जनता पार्टी). BJP leader Sushma Swaraj responded to Singh by accusing Congress of swapping coal mining contracts for bribes:

“Mota maal mila hai Congress ko” (Congress got big bucks),” Swaraj said….

“Congress has got a fat sum from coal block allocation, that is why this delay (in amending the laws) was caused. My charge is that huge revenue was generated but it did not go to the government and went to the Congress party,” Swaraj said.

Her “mota maal” charge was confirmation that the party, unfazed by government’s criticism for holding up Parliament or lack of support from non-Congress players, is in no mood to step down from its “maximalist” demand for the PM’s resignation.

In the past week and a half, Coalgate has monopolized Indian politics and all but ensured that the Indian parliament’s monsoon session* will be held up as a result of the scandal. Congress and its allies control the Indian parliament with 262 out of 543 seats so, short of a formal vote of no confidence, Singh and Congress will likely govern until the next scheduled general election in 2014. The government currently has no plans to call a trust vote itself — Singh, by daring the opposition BJP on Monday to call a trust vote, knows that leftists parties that comprise the ‘Third Front’ in the Lok Sabha would loathe supporting a BJP-led initiative to bring down the Singh government.

Joshua Keating at Foreign Policy argues that Singh will likely survive this scandal, because some BJP members are also implicated in the coal scandal. Keating lists the growing number of scandals that Singh’s government has already survived:

- accusations that Congress bribed allies in return for their support in last vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha — in 2008 over the U.S.-India nuclear pact,

- corruption with respect to awarding contracts for the Commonwealth Games,

- the ‘2G scam,’ whereby the government sold mobile phone bandwidth at a loss of $30 billion to the Indian government, and

- most ironically, the 2011 firing of the government’s anti-corruption chief PJ Thomas on corruption charges.

But it’s not been a good year for Singh — or for India — and while most people still believe that Singh is personally one of India’s most honest politicians, he could have a hard time weathering the latest corruption charge plaguing his party. That’s especially true now, with the entire world worried about India’s weakening economy. Just last month, Time Magazine Asia declared Singh an ‘underachiever’ in a scathing cover story.

Singh, a 79-year-old technocrat and India’s first Sikh (and first non-Hindu) prime minister, has served as prime minister since 2004, longer than anyone other than Jawaharal Nehru and Indira Gandhi. In that 2004 election, the BJP ran an overly optimistic reelection campaign with the notorious slogan of “India Shining” — Congress argued that too much of India wasn’t shining, and voters agreed.

Congress’s leader since 1998, Sonia Gandhi, is the widow of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, who was assassinated in 1991. Because Sonia was Italian-born, however, she appointed Singh as prime minister (and reappointed him after running Congress’s 2009 general election campaign, which saw Congress improve upon its 2004 result). So for the past eight years, Sonia has continued as the influential Congress party leader with Singh serving as India’s head of government, a scenario that has sometimes led to confusion as to who really runs India.

Prior to 2004, Singh was best known for his stint as finance minister from 1991 to 1996, when he spearheaded reforms to a state-heavy and sclerotic economy — including an end to the much-maligned, bureaucratic ‘license raj’ system. He’s been less successful a reformer as prime minister, however, and the country still struggles with corruption and significant amounts of bureaucratic hassle, especially as regards foreign investment.

This may have been fine in Singh’s first term, when nearly double-digit growth lifted 40 million Indians out of poverty, but growth slowed to just 6.86% in 2011 and may well end up at around 5% in 2012. While 5% growth would be gangbusters for a developed economy, it marks an ominous sign for India, which remains a developing country and needs high GDP growth in order to achieve a middle-income economy. Even worse, India’s problems may lead credit ratings agencies to strip the country of its investment-grade rating, putting India in danger of becoming the first “fallen angel” among the highly-feted ‘BRIC’ countries.

Under these conditions, then, Singh is more vulnerable a target than at any point in his eight years as prime minister. It’s still more likely than not that Singh will muddle through, but the timing of Coalgate may well be that crucial, last, lost opportunity for a government that’s finding itself increasingly lacking the ability to control India’s political agenda.

* The Lok Sabha holds three sessions every year: a budget session from February to May, the monsoon session from July to September, and the winter session from November to December.

Thanks for the detailed analysis! It was eye-opening.