Two months ago, Colombia’s president Juan Manuel Santos, a former defense minister, who launched the most wide-ranging peace talks with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), looked like a lock for reelection.![]()

Since late March, however, Santos has flatlined in the polls and his conservative rival, Óscar Iván Zuluaga, has nearly doubled his support — to the point where Santos and Zuluaga are now tied heading into the first round of the presidential election on May 25. Some polls show Zuluaga outpacing Santos in the runoff vote, which will take place on June 15 if, as widely predicted, no candidate wins a 50% majority this weekend.

The race has largely (though not entirely) become a referendum on the FARC peace talks, the most serious attempt by any Colombian government to seek a truce with the guerrilla movement since it began in 1964. Santos has become the ‘peace’ candidate, arguing that the negotiations are making steady progress and that voters should give him a mandate to continue the talks.

Zuluaga and his political mentor, former president Álvaro Uribe, argue that it’s wrong to offer incentives to FARC leaders, railing that they belong in prison, not discussing the possibility of winning seats in Colombia’s Congreso (Congress).

Zuluaga’s election would impose new conditions on the peace negotiations that would almost certainly bring them to an abrupt end, and he would return to the military-style campaigns designed to eradicate and eliminate FARC that were common in the Uribe era. Though Uribe presided over the widespread pacification of Colombia in the mid-2000s, Santos has argued that the FARC has been so weakened that it’s time for negotiations.

Most Colombians long ago lost patience with FARC, which has increasingly turned to drug trafficking to finance its Marxist guerrilla activities, and most Colombians also lost patience with the drug-financed right-wing paramilitary units that sprang up in the 1980s and 1990s in resistance to FARC. Voters seem willing to support Santos’s efforts to normalize relations with FARC if the talks will end the violent standoff for good.

FARC, for its part, seems to be working to bolster Santos’s political standing, declaring a unilateral ceasefire between May 20 and May 28, and working to complete the third of five issues-based agreements this week. The accord addresses controlling trade in illegal drugs. Zuluaga and Uribe argue that it’s unwise to discuss drug policy with FARC, but Santos has argued that this accord in particular could eradicate what’s left of the illegal coca trade in Colombia.

In an Ipsos poll conducted between March 14 and 16, Santos (pictured above) led with 24% of the vote, while Zuluaga was tied in second place in single digits, along with the candidate of the Alianza Verde (Green Alliance), Enrique Peñalosa, and the candidate of the Polo Democrático Alternativo (Alternative Democratic Pole), Clara López. With 19% of survey participants proclaiming they would cast a blank vote and with another 27% of voters undecided, however, the race was still fluid.

In an Ipsos poll conducted between May 13 and 15, Zuluaga led with 29.5%, with 28.5% for Santos, 10.1% for López, 9.7% for the candidate of the Partido Conservador Colombiano (Colombian Conservative Party), Marta Lucía Ramírez, and just 9.4% for Peñalosa, whose support was rising in late March and April. It’s been a particularly brutal fall for Peñalosa, who was the only candidate throughout the spring who seemed able to defeat Santos in a runoff.

The election campaign has turned nasty this month, with dual scandals implicating both Santos and Zuluaga — and both of them involve the nasty intersection of politics and illegal drugs in Colombian politics.

Two weeks ago, Santos’s campaign manager, J.J. Rendon, a Venezuelan political operative who’s something akin to the Karl Rove of Latin American politics, resigned after he was accused of receiving $12 million for his role in preventing the extradition of a handful of Colombian drug traffickers to the United States. Rendon didn’t deny intervening, but he denied accepting money.

But the more serious scandal broke last week, when Zuluaga and his former campaign manager, Luis Alfonso Hoyos, were shown in video footage allegedly receiving a briefing from a campaign consultant, Andres Sepulveda, on the FARC talks based on illegal surveillance. Though Sepulveda has since been arrested, Zuluaga has argued the video is a fabrication. Although the scandal could ultimately result in criminal charges for Zuluaga, it’s even more damaging as a reminder of the civil liberties abuses of the Uribe era. Nonetheless, the accusations (so far) haven’t seemed to dent Zuluaga’s growing lead.

So what’s going on? What explains Zuluaga’s meteoric rise?

Here are six reasons that explain why Zuluaga is now the slight favorite to become Colombia’s next president.

1. Zuluaga has (somewhat) staked out his own identity

As voters have gotten to know Zuluaga on the campaign trail, they’ve gotten to know a candidate who has a very different style than his political benefactor, Uribe.

Zuluaga, who is more soft-spoken and less visceral than the conservative former president, has increasingly shown Colombians his own personality as the campaign has unfolded. To some extent, this was inevitable.

Zuluaga, Uribe’s former finance minister, was initially seen as Uribe’s replacement, due to term limits that prohibit Uribe, Colombia’s president between 2002 and 2010, from seeking a third term. Uribe supported Santos, his former defense minister, in the 2010 election, but as Santos moved to conduct serious negotiations with FARC, Uribe acrimoniously broke with Santos and formed a new party, Centro Democrático (Democratic Center) last year.

That doesn’t mean Zuluaga is necessarily his own man — he routinely campaigns with Uribe and, if he wins, Uribe is executed to play a major role in governing Colombia. But as voters have gotten to know more about Zuluaga, they seem to like him.

2. Colombians aren’t basing votes solely on the

FARC peace process

Though Santos, probably accurately, argues that a final peace accord with FARC could significantly boost Colombian GDP, Zuluaga has been more focused on short-term economic support.

The economy has grown steadily over Santos’s presidency — Colombia achieved GDP growth of 4.0% in 2010, 4.6% in 2011, 4.0% in 2012 and 4.3% last year. But those gains haven’t necessarily filtered down to most Colombians. The economy’s growth is based on mining and services, while Colombia’s farmers and manufacturers are struggling.

Zuluaga has probably done a better job reaching frustrated voters with his promises to create more jobs and enhance social spending, which have become much more pressing everyday concerns to most Colombians than FARC bombings.

3. Uribe’s growing political strength

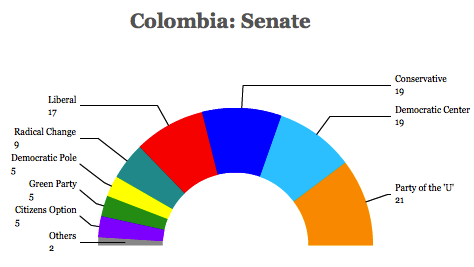

In the March congressional elections, Uribe (pictured above) and his Democratic Center, made impressive gains for a first-time party. Uribe himself won a seat in the upper house of the Colombian Senado (Senate), running on the slogan of ‘mano firme, corazón grande.’

While it doesn’t have as much strength as the ‘Santos bloc,’ its success was a clear sign there is still an appetite for Uribe’s hardline approach — and should have been a warning to Santos and his allies.

The Partido Liberal Colombiano (Colombian Liberal Party), the Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (Social Party of National Unity, ‘Party of the U’) and Cambio Radical (Radical Change) are all supporting Santos’s reelection.

The Conservatives, who are fielding their own candidate in the first round, could wind up being the key bloc in Colombia’s Congreso.

No matter who wins the presidential election, neither Santos nor Zuluaga are assured of a pliant majority in the Congreso for the next four years.

4. Colombia’s electorate is especially volatile

It’s notable that early polls showed such a high number of undecided and ‘blank ballot’ voters. To the extent that Santos led early surveys, it was with well under 50% of the vote, and often in the 20% to 30% range, far below what you would expect for an incumbent head ed toward a secure reelection.

But what’s most interesting is that Santos has essentially remained in the 20% to 30% range, even as Zuluaga has surged and Peñalosa, who at one point registered between 15% and 20% support in some surveys, has crashed. It’s hard to believe that the pro-peace, good-government Peñalosa’s supporters abandoned him for the hardline conservative, Zuluaga. Instead, as undecided voters and soft Santos supporters transferred their support to Zuluaga, voters who support the FARC negotiations appear to have shifted from Peñalosa to Santos — not out of love for Santos, but out of fear that Zuluaga might truly win the election. It’s doubtful that we’ll ever have the detailed data to know, but it sure seems like the Santos base in February would look a lot different from the Santos base today.

5. Santos has an image problem

Santos hasn’t exactly worked to make himself look like a strong leader. He’s refused to take part in a presidential debate, and he could still do more to step out of the presidential bubble. It didn’t help his image when, due to the unfortunate effects of his treatment for prostate cancer, Santos appeared to wet himself in public earlier in March, drawing unfair international attention.

But he has also seemed weak in his role in the ongoing legal drama over Bogotá’s mayor, Gustavo Petro.

Petro, a leftist and a more M-19 rebel, was removed from office by Colombian inspector-general Alejandro Ordóñez over the dubious claim that he exceeded his powers during a December 2012 garbage strike. When Colombian courts refused to overturn the decision, which also banned Petro from politics for 15 years, Santos replaced him in March with his own candidate. But after the city’s superior tribunal ruled in April that Petro’s ouster violated a ruling of the Inter-American Human Rights Commission, Santos quickly reinstated Petro.

Not only has the entire process weakened the perception of Colombia’s justice system, it’s made Santos look like a passive actor in a debate that involves what’s traditionally been the second-most important elected office in Colombia.