Juan Manuel Santos, Colombia’s president, is officially in trouble. ![]()

After the first round of Colombia’s residential vote today, Santos finished around 3.5% behind Óscar Iván Zuluaga, a more hardline conservative backed by former president Álvaro Uribe, whose campaign won increasing support from voters over the past two months.

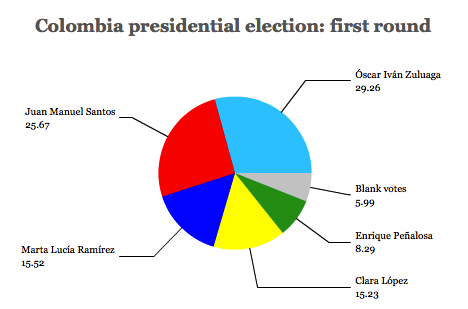

Here are the results:

As widely expected prior to today’s voting, Zuluaga and Santos will now advance to a runoff on June 15.

Santos was first elected in 2010, running with Uribe’s support and on his record as defense minister under Uribe. The former president is best known for his militarized campaign against what remained of Colombia’s drug cartels in the 2000s and its leftist guerrillas, notably the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), is now opposing Santos. Though Santos largely helped Uribe carry out his quasi-military campaign against the Marxist FARC, which has been waging an insurgency against the Colombian government since 1964, Santos has opened the most comprehensive and promise peace negotiations with FARC to date.

Santos’s narrow first-round loss may actually bolster his chances in the runoff. Despite Zuluaga’s surge over the past two months, the runoff will almost certainly become a referendum on the FARC negotiations.

Expect the Colombian left to line up behind Santos as a matter of national unity to save the peace talks, including those voters who supported López and Peñalosa in the first round (it’s very difficult to imagine Zuluaga winning over many of their supporters) and, probably, a fair number of Ramírez supporters as well. If you add up the combined support of Santos, López and Peñalosa, it’s over 49% of the first-round vote. Given a choice between continuing the FARC talks or returning to a more militarized, Uribe-style approach, it’s easy to believe that a ‘peace front’ will emerge to bolster Santos on June 15.

So on paper, Santos has the easier route to victory — but that’s only so long as Santos holds onto his first-round base. There’s a chance that Zuluaga, having weakened Santos, could pull soft voters away from Santos if he’s aggressive enough in the next three weeks.

But the last month of the campaign has been characterized by scandal and dirty politics. Hackers with connections to the Zuluaga campaign are accused of illegally obtaining confidential information related to the FARC negotiations, while Santos’s campaign manager, is accused of taking millions in exchange for intervening on behalf of drug dealers trying to avoid extradition to the United States. There’s no way to know whether new revelations might change the dynamic of the race in the next three weeks in unpredictable ways.

Moreover, Zuluaga seems to have outmaneuvered Santos with his strong stand against the FARC, making Santos seem weak in comparison. Meanwhile, Zuluaga has arguably also outmaneuvered Santos on bread-and-butter economic issues. While the economy has grown at a stead pace of between 4% and 5% in the past four years, growth has been uneven, and Zuluaga has fashioned a more populist campaign based on promises of greater social spending and higher employment.

The biggest surprise might be that Enrique Peñalosa, a moderate, anti-corruption candidate, who served as the mayor of Bogotá between 1998 and 2001, finished far behind in fifth place. At one point earlier this spring, Peñalosa had surged into second place, and several polls showed that he would even defeat Santos in a runoff. But as Zuluaga became an increasingly serious contender, Peñalosa’s support collapsed, and even top leaders within the newly formed Alianza Verde (Green Alliance) defected to indicate their support for Santos.

Marta Lucía Ramírez, the candidate of the Partido Conservador Colombiano (Colombian Conservative Party), won just over 15% of the vote, as did Clara López, the candidate of the leftist Polo Democrático Alternativo (Alternative Democratic Pole).

Uribe, who formed a new political party last year, Centro Democrático (Democratic Center), won a seat in the Colombian Senado (Senate) in congressional elections earlier in March.

Santos is backed by a trio of parties, the centrist Partido Liberal Colombiano (the Colombian Liberal Party), the Partido Social de Unidad Nacional (Social Party of National Unity, ‘Party of the U’), and Cambio Radical (Radical Change).