Though it’s only been two weeks since South Koreans upended polls to deliver a shock verdict in parliamentary elections, the country is now pivoting toward its next presidential election — which is nearly 20 months away. ![]()

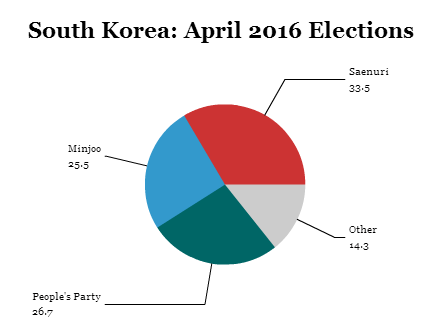

Taking place nearly two-thirds of the way through the five-year term of president Park Guen-hye (박근혜), the election was an opportunity for Park to solidify her grip on the National Assembly, as well as her own party, the conservative Saenuri Party (새누리당, ‘New Frontier’ Party) by winning a more solid majority in South Korea’s 300-member unicameral legislature, the National Assembly (대한민국 국회).

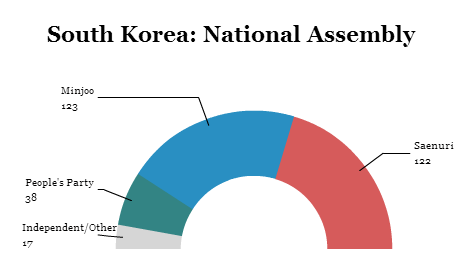

Despite poll predictions that Saenuri would take advantage of a split opposition and win an even wider majority, the party instead lost ground, falling further away from an absolute majority, winning just 122 seats, 24 fewer seats in the National Assembly than the party held before the elections. Park, like all South Korean presidents, is limited to a single term in office and, in some regards, she became a lame duck president from the first days of the 2013 inauguration of the country’s first female president. That hasn’t stopped Park from wielding power through a very strong executive branch.

Saenuri’s defeat, however, and Park’s failures in particular, mean that the country is now shifting towards the posturing among Park’s opponents, including those within other Saenuri Party factions, to plot a path to the presidency in an election that will not be held until December 20, 2017.

The results will give hope to the traditional center-left opposition party, the newly renamed (as of last December) Minjoo Party (더불어민주당), a successor to what used to be called the Democratic United Party, which won 123 seats — one more than Saenuri. That could embolden several top figures within the party to mount a 2017 presidential bid, including Moon Jae-in (문재인), the party’s former leader and its 2012 candidate against Park.

But the results will give even more hope to the newly formed, as of February, People’s Party (국민의당), an alternative liberal party that has pulled supporters away from Minjoo. Its leader is Ahn Cheol-soo (안철수), a software entrepreneur, businessman and academic, who burst onto the political scene as a potential presidential candidate in 2012. He will now almost certainly be a contender in the 2017 election. Though the People’s Party only won 38 seats, it actually won more votes than Minjoo.

So what does South Korea’s election mean for the rest of Park’s administration and for 2017? Continue reading Koreans look to 2017 after Park’s governing party loses seats