Amid growing political turmoil, during which the interim General National Congress (GNC) has lost even the pretense of control, Libyans will vote for a new ‘permanent’ parliament in elections tomorrow as the country slides into ever greater insecurity.

Since the ousting of Muammar Gaddafi in August 2011, repeated attempts to introduce a measure of effective governance have failed, first by the National Transitional Council, and now by the GNC.

On the eve of Libya’s elections, international observers say the voting was organized much too hastily and without adequate preparation. The risk is that, following the July 2012 elections for the GNC and the February 2014 constituent assembly elections to appoint a body to write Libya’s new constitution, a third set of botched elections could further undermine democracy. That’s especially true if voters in the eastern Libya of Cyrenaica don’t particularly bother to turn out. Just 1.5 million voters have registered to participate in the elections, down from the 2.865 million voters that registered for the 2012 vote. If those numbers hold up, turnout tomorrow will be much lower than the 1.76 million that participated in July 2012.

* * * * *

RELATED: Libya hits new security low as interim prime minister resigns

* * * * *

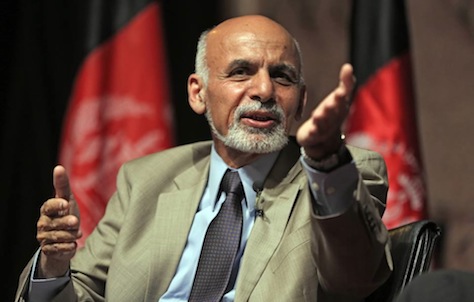

Rather than wait for a new constitution to come into effect, the GNC hastily renamed itself the ‘House of Representatives,’ and late last month announced elections for June 25 to elect 200 members to the newly formed parliament. The GNC acted under considerable pressure from militia forces loyal to former Libyan general Khalifa Hifter (pictured above), who is waging an increasingly effective campaign, chiefly in Benghazi, to eliminate Islamists and Islamist-sympathetic militias throughout the country.

Since the collapse of former prime minister Ali Zeidan’s government in March, Libyan governance has essentially crumbled. Zeidan, a liberal human rights attorney who lived in Geneva before returning to Libya after the 2011 civil war, was first elected prime minister in November 2012 after a contentious vote within a body that, from the outset, was severely divided between liberals and Islamists. Though elected with the support of liberals, Zeidan only narrowly defeated Mohammed Al-Harari, the candidate of the Islamist Justice and Construction Party (حزب العدالة والبناء), the political wing of Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood.

Over the course of his premiership, Zeidan presiding over an increasingly fractious interim government that gradually lost control of much of the country outside Tripoli. In fairness to Zeidan, it’s not clear if any government could have effectively asserted control over Libya over the past two years. As security increasingly faltered, Zeidan himself was kidnapped from a Tripoli hotel in October 2013 and held for hours in an aborted coup attempt.

The final straw for Zeidan came earlier this year when, after growing tensions with conservative militias in Benghazi, eastern rebels commandeered an oil tanker, the Morning Glory, and sailed it halfway across the Mediterranean Sea before US Navy SEALS apprehended it. Though Zeidan initially fled Libya, he returned earlier this week, claiming that he is still legally Libya’s prime minister.

His successor, former defense minister Abdullah al-Thinni, tried to step down nearly a week later as interim prime minister after an attempt on his life. The GNC’s replacement candidate, Ahmed Maiteeq, a Misrata native and businessman, was disputed, and Libya essentially had two competing potential prime ministers until the Libyan supreme court ruled on June 9 that Maiteeq’s election was invalid, thereby restoring the reluctant al-Thinni as interim prime minister.

Hifter’s rise has coincided with the political and security tumult. With significant support in western Libya, militia forces loyal to Hifter effective shut down the GNC earlier this spring, accelerating the decision to hold what amounts to snap elections for the new parliament. Today, Hifter’s leading the most notable anti-militia effort in Benghazi, after declaring himself the leader of ‘Operation Dignity’ in mid-May. Though Hifter’s offensive isn’t sanctioned by the GNC (nor by al-Thnni nor Zeidan nor Maiteeq), his efforts haven’t necessarily been unwelcome by some members of the Libyan government, notably within the interior ministry, which has struggled to implement law and order on a nationwide basis.

Critics worry, however, that Hifter has aims to become a new Gaddafi-like dictator. Hifter has expressed high regard for Egypt’s newly elected president, former army chief Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, especially regarding el-Sisi’s crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood within Egypt. Critics worry that Hifter is launching a military offensive to win the same kind of quasi-authoritarian power that El-Sisi now enjoys in Egypt.

Intriguingly, Hifter is actually a US citizen. Once a Gaddafi partisan, Hifter led a disastrous military campaign in the 1980s in Chad. After his defeat and his subsequent capture by Chadian forces, Hifter joined forces with the anti-Gaddafi opposition and fled to exile, living in northern Virginia between 1990 and 2011, when he returned to Libya to help lead the anti-Gaddafi rebel forces. He was initially mistrusted by other leading rebel generals, however, and he’s the subject of significant speculation that he once worked with US military or other clandestine government officials.

That means, as national voting takes place, Hifter’s forces are engaged in a dangerous showdown in Libya’s second-largest city against Ansar al-Sharia (كتيبة أنصار الشريعة), an Islamist militia that wants to adopt harsh shari’a law across Cyrenaica, the oil-rich region that’s home to Benghazi, if not the entire country.

But it’s not the only place where violence is marring the election campaign. In Sabha, the historical capital of the southern Fezzan region, largely desert and sparsely populated, a parliamentary candidate was killed by gunmen on Tuesday.

Ibrahim al-Jathran, another militia leader, who also fought to topple Gaddafi in the 2011 civil war, last summer took control of four eastern ports, thereby shutting down much of the Zeidan government’s ability to export oil. In a deal with Libya’s interim government soon after Zeidan’s ouster, Jathran permitted two of the ports to reopen, but oil production is still just around 12.5% of Gaddafi-era levels, gas stations in Tripoli are closed, and Libya remains subject to recurring power outages.

Despite some temporary progress, Jathran still advocates a much more autonomous Cyrenaica, if not outright independence. Though Cyrenaica is home to 1.6 million people (the bulk of Libya’s 5.7 million people live in Tripolitania, along Libya’s northwestern coast), much of Libya’s oil wealth is located in the eastern region.

As if that weren’t enough, US special forces last week arrested Ahmed Abu Khattala, a Benghazi-based militia leader believed to be responsible for the September 2012 attack on the US consulate in Benghazi. Though Khattala’s arrest was widely hailed in the United States, Libyans have largely decried what they call the US’s violation of Libya’s national sovereignty.

All of these issues — the standoff between Hifter and Ansar al-Sharia, Khattala’s arrest, the blockage of the country’s dwindling oil exports — threaten to dwarf this week’s election. The February elections to appoint the constitutional constituency assembly attracted just 500,000 voters. If the June 25 parliamentary elections feature similarly low turnout, it will be hard to argue that any party or group will have won much of a mandate for anything.

That’s especially true if Islamists, which have typically been the most organized forces in elections held across North Africa since the Arab Spring revolts of early 2011, win the largest share of seats in tomorrow’s vote. That could empower Islamist militias in Cyrenaica and beyond, setting the scene for a long war of attrition between Hifter’s supporters and Islamist militias.

Even before Zaidan took power, Libya has struggled in the post-Gaddafi era to form a coherent government, in no small part due to the failure of the Gaddafi regime to establish truly national institutions in Libya, where he came to power in a 1969 military coup, just 18 years after the country won full independence from British and French oversight. Under both Ottoman rule, beginning in 1510, and Italian rule, between 1912 and 1947, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were governed as discrete provinces, with modern ‘Libya’ taking shape chiefly as a political construct in 1951. Up until independence, when the British relinquished full sovereignty over Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, the French were administering Fezzan separately.

Mahmoud Jibril, a secular liberal, served as Libya’s first interim leader, between March 2011 and October 2011 when he chaired the executive board of the National Transitional Council. He stepped down just three days after Gaddafi was captured and killed by a mob in Gaddafi’s own hometown of Sirte. Jibril leads the National Forces Alliance (تحالف القوى الوطنية), a very mildly Islamist, liberal group that won the largest group of seats in the GNC in the July 2012 elections. At the time, however, Jibril’s influence was at its peak, and no one expects his group to repeat the successes of the 2012 election.

Abdurrahim El-Keib was elected by the National Transitional Council in November 2011, and he guided Libya through the September 2012 election of the interim GNC.

Photo credit to Reuters / Esam Omran Al-Fetori.

![]()

![]()