Despite widespread international opprobrium, Indonesia executed eight prisoners earlier today, including two members of the ‘Bali Nine’ group of Australians convicted for drug offenses, four Nigerian nationals and a Brazilian national.

Indonesian president Joko Widodo, known as ‘Jokowi’ throughout the country, was elected on a platform of reform and good government. With today’s executions, and with the executions of Brazilian and Dutch nationals for similar drug offenses earlier this year, Jokowi’s international reputation lies in tatters, just six months into his administration. Mary Jane Veloso, a Filipino woman convicted of similar drug offenses, however, won a last-minute reprieve after conversations between Jokowi and Philippine president Benigno Aquino III. Veloso was allegedly duped into smuggling drugs into Indonesia, and Aquino had argued that she should be granted a stay of execution for the purposes of testifying against the traffickers who sent Veloso to Indonesia with drugs.

It’s a stupendous fall for Jokowi, who swept into office with high hopes domestically and abroad. Though the executions are not especially controversial in Indonesia, where the death penalty for drug-related offenses is popular, its beleaguered president is facing other pressures that have made it virtually impossible for him to grant clemency to the ‘Bali Nine’ and other foreign drug convicts without incurring additional political backlash, most of all from within the party that sponsored his presidential candidacy, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P, Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan). Until the executions earlier this year, Indonesia had been under a sort of unofficial moratorium for the prior four years.

* * * * *

RELATED: It’s official — Jokowi wins Indonesian presidential election

RELATED: Death penalty diplomacy presents challenge to Jokowi

* * * * *

Notwithstanding the executions, when viewed in tandem with other missteps, Jokowi risks being viewed as a coward at home and a murderer abroad. For now, Jokowi’s decision, at least domestically, is a nationalist moment reaffirming the sovereignty of the world’s fourth-most populous country, but it comes at the risk of painting Indonesia as the number-one target of anti-death penalty activists worldwide.

Though Brazil and The Netherlands recalled their ambassadors from Jakarta after the January executions, the latest round of executions could bring far more destabilizing consequences for Jokowi. Australian prime minister Tony Abbott and foreign minister Julie Bishop have objected strenuously to the Indonesian government’s decision to carry out the executions.

Though ties between Australia and Indonesia are not perfect, the bilaterial relationship is seen by both countries as vital to security and trade interests. Indonesia is the largest recipient of Australian foreign aid, with Australia contributing nearly $650 million in aid to Indonesia in 2013. Cooperation, however, is an important issue with respect to the smuggling of migrants into Indonesia by boat, which peaked (along with deaths at sea) in the mid-2000s.

When Jokowi came to office, he quickly moved to reduce fuel subsidies that had hogged up nearly one-quarter of the Indonesian national budget. By January, his administration had eliminated them entirely, and the world watched with high regard for a president who seemed willing and, even more surprisingly, able to take bold steps that could liberalize Indonesia’s economy. Record-low oil prices, moreover, made early 2015 a perfect time to eliminate those subsidies.

Since then, however, Jokowi’s record has been much less impressive.

Instead of taking on widespread corruption, Jokowi instead seems to have weakened it. His initial appointment of Budi Gunawan to the Anti-Corruption Commission (KPK) was put on hold when it became clear that the KPK was investigating Gunawan for corruption. Though the entity is just a decade old, the KPK has earned considerable respect for impartiality and success. Gunawan’s appointment appeared to make a mockery of the KPK’s work, and it called into severe question Jokowi’s commitment to anti-corruption efforts. Jokowi quietly dropped the nomination, but nevertheless appointed Gunawan as the deputy national police chief earlier this month.

After signing an executive order establishing a broad increase in car allowances for government officials, Jokowi feebly responded to criticism that he hadn’t had time to read every regulation that crosses his desk. He’s now reconsidering that as well.

Most emasculating of all, Jokowi sat at the PDI-P party congress last month while its leader, former president Megawati Sukarnoputri (pictured above), the daughter of Indonesia’s founding president, Sukarno, essentially scolded Jokowi for not lining up behind Megawati:

“It goes without saying that the President and Vice President must toe the party line, because the party policies are consistent with what the public wants,” she claimed. Her voice rising, Megawati warned Jokowi against breaking his campaign promises. “I have said this again and again, please stick to the Constitution. Fulfill your campaign promises because they are your sacred bond with the people,” Megawati said, to the thunderous applause of party members attending the national congress at the Inna Grand Bali Beach Hotel.

Megawati has mocked Jokowi for not expediting the executions of the ‘Bali Nine,’ and she has somewhat controversially linked drug offenses with the rise of HIV/AIDS in Indonesia. As vice president, Megawati became president in 2001 when Abdurrahman Wahid was removed from office. She failed in both 2004 and 2009 to win election in her own right, losing both times to popular former army general Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who left office to middling reviews last October. Jokowi’s push to reinstate Indonesian executions contradicts the conventional wisdom that Yudhoyono (who is known by his initials, ‘SBY’) cared too much about international opinion.

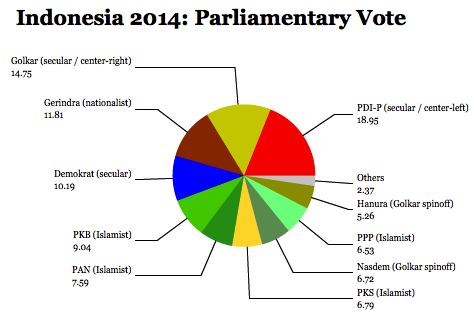

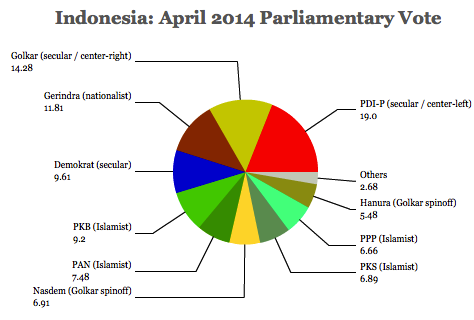

In the meanwhile, Jokowi has raised eyebrows by reaching out to his former rival in last year’s presidential election, Prabowo Subianto, who leads a nationalist party, Gerindra (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, the Great Indonesia Movement Party) that, along with the more market-friendly Golkar (Partai Golongan Karya, Party of the Functional Groups); and SBY’s own Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party) controls the Indonesian legislature.

If Jokowi were to abandon the PDI-P and Megawati’s iron fist, and turn to the Golkar-Gerindra-Demokrat alliance instead, he could conceivably effect more control over Indonesia’s government. Though such a sudden switch would be unprecedented in the history of the country’s brief democratic era, it reflects the fluid nature of Indonesian presidential coalitions. Moreover, Jokowi’s vice president, Jusuf Kalla, is a former Golkar leader who also served as SBY’s first vice president in the 2000s.

Nothing, at this point, will bring back any of the executed victims of Indonesia’s death penalty. Jokowi, whose term runs through 2019, will eventually have to make amends with Australia and the international community. For now, though, his global legacy begins with the stain of reintroducing the death penalty to his country, even as capital punishment is quickly being eradicated throughout much of the developed and developing world alike.

![]()

![]()