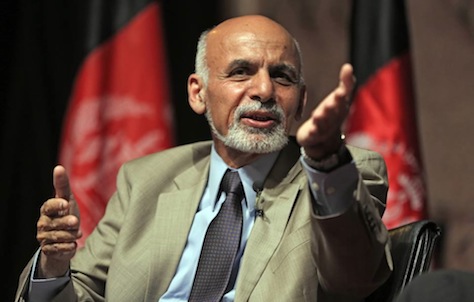

Afghanistan’s election officials have announced the results of the country’s June 14 presidential election, and the surprising winner seems to be former finance minister Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai, who trailed widely after the results of the April 5 first round. ![]()

The provisional result gives Ghani (pictured above) 56.44% of the vote, while rival Abdullah Abdullah won 43.56%.

It’s actually not so incredibly surprising in light of Abdullah’s denunciation over the past weeks of the vote-counting process, a sure sign that Abdullah realized he was in danger of losing the race.

On June 18, just four days after the election, Abdullah called for a suspension in the vote count by the Independent Election Commission, arguing that votes were counted in areas where voting hadn’t even taken place due to security problems.

* * * * *

RELATED: Afghanistan hopes for calm as

key presidential election approaches

RELATED: Why there’s reason for optimism

about the Afghan troop drawdown

* * * * *

Five days later, on June 23, Zia ul-Haq Amarkhail, the secretary-general of the IEC, resigned, an implicit admission that there’s at least some substantive basis to the fraud charges. The IEC delayed the original announcement of preliminary results, due on July 2, for five more days to investigate further the charges of voter fraud. As the BBC reports, votes are being re-checked at more than 7,000 polling stations, amounting to nearly one-third of all voting stations, and the commission will check nearly 4 million votes in an election that drew just 6.6 million voters in the first round:

Chief election commissioner Ahmad Yusuf Nuristani stressed that the results were not final and acknowledged that there had been “some mistakes in the overall process”.

“It is only initial results,” he told a news conference in Kabul. “There is a chance of change in the overall figure…. The announcement of preliminary results does not mean that the leading candidate is the winner.

“We announced preliminary results today and it is now the complaints commission’s duty to inspect this case.”

So what’s going on in Afghanistan? After the first round of voting in the spring appeared largely to avoid the mistakes of the disastrous 2009 presidential election, the country now faces a protracted battle between Ghani’s chiefly Pashtun supporters and Abdullah’s chiefly Tajik supporters.

Is Abdullah leading a sour-grapes campaign in the face of evidence that his support was slipping between the April vote and the June runoff? One Glevum Associates opinion poll from early June suggests that Ghani led Abdullah by 49% to 42%. Given the difficulty of conducting a credible poll in a country with such severe security concerns, it’s worth taking any poll with some considerable doubts.

Moreover, there’s nothing extraordinary in Ghani’s past record that suggests he would lead a campaign to falsify an election. After serving as outgoing president Hamid Karzai’s finance minister from 2002 to 2004, he refused to participate in any further high-level ministries out of concerns about corruption in Karzai’s government. Instead, he became the chancellor of Kabul University and ran a relatively lackluster campaign for the Afghan presidency in 2009. In 2006, he was among the frontrunners to become the next secretary-general of the United Nations.

As finance minister, he introduced a new currency, reformed the Afghan treasury and took other measures that largely stabilized the Afghan economy after decades of Soviet, Taliban and other homegrown disruption, winning an international reputation as a thoughtful and capable policymaker. He also cracked down, to the extent possible, on burgeoning corruption in the Karzai administration. All of those are reasons to believe that Ghani would lead a strong, reformist government in Kabul, but that task will be complicated if nearly half of Afghan voters believe his presidential victory was fraudulent.

Moreover, there’s so much evidence of vote fraud that it’s hard to believe it’s just the smoldering rants of a losing Abdullah. International observers widely agreed that the 2009 debacle involved credible, material allegations of fraud, and it took US and European intervention to convince Karzai to relent to holding any sort of runoff. Ultimately, days before the second vote, Abdullah withdrew from the race, unconvinced that Afghanistan’s election commission had sufficiently reformed, effectively sealing Karzai’s reelection. There’s so much institutional corruption among Afghanistan’s politicians and its tribal warlords that significant voter fraud could take place even outside Ghani’s direct involvement.

The nightmare scenario is that voters genuinely moved toward Ghani between the two elections, notwithstanding widespread fraud.

It’s rare for a leading candidates vote share to fall between a first round and a runoff. Abdullah won 45.00% in that election, while Ghani won just 31.56% of the vote.

If the provisional runoff results are valid, it means that Ghani nearly doubled his vote share between April 5 and June 14. More incredulously, it means that some initial Abdullah supporters switched to Ghani, even though Abdullah won the endorsement of Zalmai Rassoul, the third-place finisher.

* * * * *

RELATED: Did Abdullah just win the Afghan presidency?

* * * * *

Rassoul until recently served as Karzai’s foreign minister, had the support of Quayum Karzai, the president’s brother, and was largely believed to be the unofficial candidate of the Karzai regime. Rassoul actually won Kandahar province in the first round, on the strength of tribal supporters in Karzai’s home region, and he also performed strongly in neighboring Helmand province. Rassoul is also a member of the Mohammadzai tribe, the same tribe as the Afghan monarchy that ruled the country between 1826 and 1973. It was widely expected that Rassoul’s support would bring along the additional southern Pashtun votes that Abdullah would need to secure victory.

Fraud aside, it looks like Rassoul wasn’t able to deliver that support.

Moreover, if Afghan voters did have second thoughts about Abdullah, one reason could be ethnicity. Though Abdullah is half-Pashtun and half-Tajik, many Pashtuns supported Ghani, and Abdullah himself is strongly associated with the Tajik leadership of the Northern Alliance that assisted the US-backed operation to oust the Taliban in 2001. Pashtuns comprise around 42% of Afghanistan’s population (Tajiks comprise around 27%), and Afghanistan has for the last two centuries been ruled by Pashtun monarchs or civilian Pashtun presidents, excepting two small breaks of Tajik rule, neither of which were incredibly distinguished. The first came during the administration of Babrak Karmal, who led the country with Soviet direction from 1979 to 1986. The second was from 1992 to 1996, when Burhanuddin Rabbani presided over civil war-like conditions in Kabul and beyond, in a period of anarchy between the end of Soviet occupation and the rise of Taliban rule.

So it’s easy to understand why Pashtun voters, suddenly alarmed at the rise of a president more culturally Tajik than Pashtun, might flock en masse to Ghani, notwithstanding Abdullah’s early lead and Rassoul’s endorsement. What’s more, one of Ghani’s two running mates, Abdul Rashid Dostum, ranks among the most notable and notorious of the Uzbek warlords. The Uzbek population is the third-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan and, though it numbers around 9%, a united Pashtun-Uzbek front could easily explain Ghani’s apparent success.

With the fraud accusations already rising to serious levels, it’s unclear if any outcome would now be accepted by both candidates. If the final results confirm Ghani’s surprisingly lopsided victory, Abdullah will remain unconvinced of the vote’s propriety. If the final results show an Abdullah victory, the gap between the preliminary and final results will be so damning as to give Ghani cause for suspicion.

A ‘do-over’ runoff, even under a new election commission and with significant changes to the voting processes, would hardly engender much higher levels of trust, because each side would forever remain convinced that it won the initial election. A new runoff would also be a perfect target for Taliban insurgents as its summer offensive gathers steam.

One thought on “Is Ghani’s Afghan preliminary electoral victory a fraud?”