The conventional wisdom is that with the growing crisis in the rest of Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan has never been better.

‘Better’ is a relative term, of course.

But for a region that also features severe corruption, intense political rivalries, a bloated and unaffordable public sector and fiscal dependence (for now, at least) on Baghdad, Iraqi Kurds have reason for optimism.

With Kurdish peshmerga forces in full control of Kirkuk, the Kurdish regional government can now lay claim to the entire historical region of Iraqi Kurdistan. Former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, notorious for his crackdown against Kurdish identity and nationalism, encouraged Arabs to relocate to what Kurds (and Turkmen) consider their cultural capital.

Under Article 140 of Iraq’s newly promulgated 2005 constitution, the national government is obligated to take certain steps to reverse the Saddam-era Arabization process and thereupon, permit a referendum to determine whether Kirkuk province’s residents wish to join the Kurdistan autonomous region. Like in many areas, from energy to electricity to education to employment, Iraq’s national government has made little progress on the Kirkuk issue. Kurdish leaders now say they will hold onto Kirkuk and its oil fields until a referendum can be arranged. Realistically, there’s little that Baghdad can do to reverse Kurdish gains.

That, in time, will give Iraqi Kurdistan the oil revenues that it needs for a self-sustaining economy, in tandem with growing Turkish economic ties that crested last year with the completion of a pipeline between Kurdistan and Turkey that allows the Kurdish regional government to ship crude oil out of Iraq without Baghdad’s approval.

* * * * *

RELATED: Don’t blame Obama for Iraq’s turmoil — blame Maliki

* * * * *

In that regard, the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS or ISIL, الدولة الاسلامية في العراق والشام, ad-Dawla al-Islāmiyya fi al-’Irāq wa-sh-Shām), which now controls much of northern and northeastern Iraq, including much of al-Anbar province and northern cities like Mosul and Tikrit, has been a boon for the cause of Kurdish nationalism.

ISIS, which has newly re-christened itself simply the ‘Islamic State’ (الدولة الإسلامية), has declared a 21st century caliphate over the territory it holds in Iraq and in eastern Syria, with ambitious, if unrealistic, designs on Baghdad and parts of Jordan, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia:

Sentiment is so heady these days that the Kurdish regional president, Massoud Barzani (pictured above), despite the hand-wringing of US and Turkish officials, has called for a referendum on Kurdish independence — in months, not years:

We will guard and defend all areas of the Kurdish region – Kurd, Arab, Turkmen, Assyrian, Chaldean, all will be protected. We will endeavor to redevelop and systematize all regions of Kurdistan. We will use our oil revenue to create better and more comfortable living conditions for our citizens. And until the achievement of an Independent Kurdish State, we will cooperate with all to try to find solutions to the current crisis in Iraq. With all our might, we will help our Shia and Sunni brothers in the fight against terrorism and for the betterment of conditions in Iraq – although this is not an easy task.

Amid that backdrop, the various political parties formed a new Kurdish regional government last week, two months after Iraqi national parliamentary elections in Iraq and fully nine months after Kurdish regional elections.

As the United States leans on the Iraqi parliament to form a new government quickly, in order to combat more effectively the ISIS threat in Sunni-dominated Iraq, the Kurdish example is instructive. If it took nine months to reconstitute the Kurdish regional government, is it plausible to expect Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds to form a national government, under crisis conditions, in just two months?

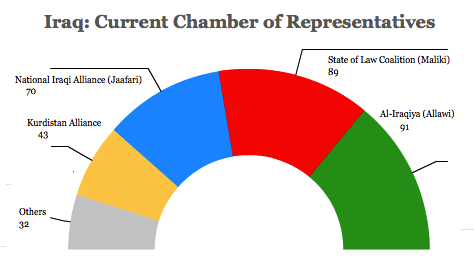

Even under calmer conditions in 2010, it took Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki nine months of coalition talks to build Iraq’s previous government. Though Maliki’s Shiite-dominated State of Law Coalition (إئتلاف دولة القانون) won the greatest number of seats after the April parliamentary elections, many Iraqis fault his heavy-handed style for the sectarian crisis in which Iraq now finds itself.

In the first meeting of Iraq’s 325-member Council of Representatives (مجلس النواب العراقي) last week, Sunnis and Kurds alike walked out on Maliki, and there’s not much hope that a second session on Tuesday will result in additional progress.

Continue reading Amid Iraqi turmoil, Kurdistan settles new regional government →

![]()