In 2002 and 2003, assistant U.S. attorney general John Yoo, at the U.S. department of justice, authored now-infamous ‘torture memos’ providing legal justification for ‘enhanced interrogation’ techniques, which the administration of U.S. president George W. Bush would proceed to employ against ‘unlawful combatants,’ and in violation of the Geneva Conventions, according to many legal scholars (outside the Bush administration, at least).

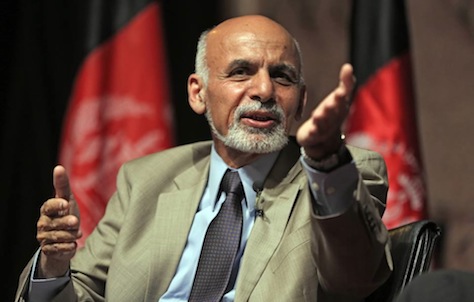

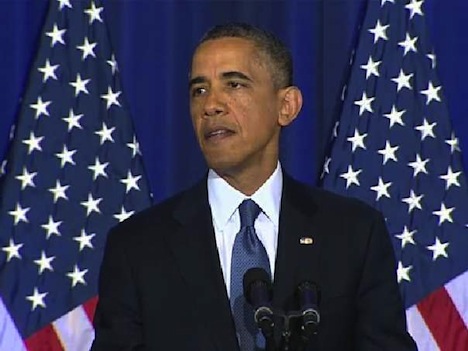

Although we don’t know who wrote it or when it was written, there’s some parallelism in the ‘white paper’ from the justice department of U.S. president Barack Obama, made public today by NBC News, offering up the legal justification for the targeted killing of U.S. citizens who are senior operational leaders of al Qaeda or an associated force of al Qaeda.

Kudos to NBC News for obtaining the memo, which requires that any such U.S. citizen must be an ‘imminent’ threat, capture of the U.S. citizen must be ‘infeasible,’ and the strike must be conducted according to ‘law of war principles.’ Each of those is defined in a manner that’s not exactly narrow — for example, as Michael Isikoff at NBC notes:

“The condition that an operational leader present an ‘imminent’ threat of violent attack against the United States does not require the United States to have clear evidence that a specific attack on U.S. persons and interests will take place in the immediate future,” the memo states.

Instead, it says, an “informed, high-level” official of the U.S. government may determine that the targeted American has been “recently” involved in “activities” posing a threat of a violent attack and “there is no evidence suggesting that he has renounced or abandoned such activities.” The memo does not define “recently” or “activities.”

The United States, first under the Bush administration, but at a vastly accelerated pace under the Obama administration, has used unmanned drones to attack targets in Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan (to say nothing of what we don’t know about their use in more conventional military theaters, such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya over the past decade) — it seems reasonable to believe that drones could soon be used in Afghanistan after U.S. troops leave that country next year, and U.S. capability for drone use in Mali or elsewhere in north Africa would likewise not be a difficult task.

The leaked memo comes day before Congressional hearings on John Brennan’s appointment as Obama’s new director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

There’s not much I can add to what others have already said about the Obama administration memo, though it may well come to define this administration’s unique ‘addition’ to the expanding nature of executive power in the United States, to the detriment of U.S. constitutional civil liberties and even international law.

In September 2011, the United States attacked two U.S. citizens, Anwar Awlaki and Samir Khan, in a drone attack in Yemen and, more perhaps troubling, killed Awlaki’s 16-year old son, Abdulrahman, also a U.S. citizen, in a subsequent attack.

Glenn Greenwald, writing for The Guardian in a long and thoughtful takedown of the leaked memo, takes special offense with the lack of due process for accused targets:

The core distortion of the War on Terror under both Bush and Obama is the Orwellian practice of equating government accusations of terrorism with proof of guilt. One constantly hears US government defenders referring to “terrorists” when what they actually mean is: those accused by the government of terrorism. This entire memo is grounded in this deceit….

This ensures that huge numbers of citizens – those who spend little time thinking about such things and/or authoritarians who assume all government claims are true – will instinctively justify what is being done here on the ground that we must kill the Terrorists or joining al-Qaida means you should be killed. That’s the “reasoning” process that has driven the War on Terror since it commenced: if the US government simply asserts without evidence or trial that someone is a terrorist, then they are assumed to be, and they can then be punished as such – with indefinite imprisonment or death.

In contrast, Jameel Jaffer, the deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union has written a quick reaction that’s subdued in contrast to Greenwald’s response:

My colleagues will have more to say about the white paper soon, but my initial reaction is that the paper only underscores the irresponsible extravagance of the government’s central claim. Even if the Obama administration is convinced of its own fundamental trustworthiness, the power this white paper sets out will be available to every future president—and every “informed high-level official” (!)—in every future conflict. As I said to Isikoff, that’s truly a chilling thought.

Although the memo itself could well stand as an important turning point in the Obama administration’s controversial justification for executing U.S. citizens without due process, what seems even clearer is that as Obama’s second term unfolds, we can expect the continuation and proliferation of the use of drone attacks. Given the zeal with which U.S. policymakers are apparently pursuing U.S. citizens in Yemen, Pakistan and Somalia, it seems certain that the Obama administration is even more audacious in its approach to the protection of non-U.S. citizens.

Will Wilkinson at The Economist has recently argued that the Obama administration’s drone program as a whole fails the Kantian principle of ‘universal law’ — i.e., that the United States might not enjoy being on the receiving end of its own logic:

The question Americans need to put to ourselves is whether we would mind if China or Russia or Iran or Pakistan were to be guided by the Obama administration’s sketchy rulebook in their drone campaigns. Bomb-dropping remote-controlled planes will soon be commonplace. What if, by another country’s reasonable lights, America’s drone attacks count as terrorism? What if, according to the general principles implicitly governing the Obama administration’s own drone campaign, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue turns out to be a legitimate target for another country’s drones? Were we to will Mr Obama’s rules of engagement as universal law, a la Kant, would we find ourselves in harm’s way? I suspect we would.

As such, stunning as today’s news is, it’s worth pausing to consider the effects on each of the three countries where the Obama administration is known to be operating drones — as critics note, the drone attacks could ultimately backfire on long-term U.S. interests by antagonizing Muslims outside the United States and potentially radicalizing non-U.S. citizens into supporting more radical forms of terrorism against the United States in the future.

Continue reading U.S. justice department memo justifies targeted killings of U.S. citizens abroad →

![]()