Over the weekend, US secretary of state John Kerry brokered a promising deal between the two candidates in Afghanistan’s botched, contested June 14 presidential runoff between former foreign minister Abdullah Abdullah and former finance minister Ashram Ghani Ahmadzai, both of whom have alleged fraud in the runoff. ![]()

It’s not an incredibly bad deal, and if it sticks, it will provide Afghanistan with a strong government, acceptable to supporters of both Ghani and Abdullah, that brings to power the largest and, historically dominant, ethnic group, the Pashtun, with a significant role for the second-largest group, the Tajiks, which dominate northern Afghanistan and form the plurality in Kabul, the Afghan capital.

Under the terms agreed among Kerry, Ghani and Abdullah, every single runoff vote will be audited centrally in Kabul by international observers, with representatives of both the Ghani and Abdullah campaigns present. The winner will thereupon form a national unity government that, presumably, will include supporters of both campaigns.

* * * * *

RELATED: Is Ghani’s Afghan preliminary electoral victory a fraud?

RELATED: Afghanistan hopes for calm as key presidential election approaches

* * * * *

Abdullah won the first round on April 5, by a wide margin of 45.00% to just 31.56% for Ghani, on the basis of 6.6 million voters. In the second round, preliminary results show that Ghani won 56.44% to just 43.56% for Abdullah, on the basis of 7.9 million votes — a significant increase in turnout.

It marks an astounding turn of events for Ghani. It’s especially astounding in light of the endorsement of the first round’s third-placed candidate, Zalmai Rassoul, a former foreign minister who is close to outgoing president Hamid Karzai, and who endorsed Abdullah before even all the votes of the first round had been counted. Rassoul’s support was meant to bring along key Pashtun tribal leaders, close to Karzai and Rassoul, in the southern Helmand and Kandahar provinces.

But the deal doesn’t tell us exactly what the auditing process will entail, and whether the Independent Election Commission, whose director resigned in the wake of the second round after Abdullah lodged credible, serious complaints, will play a significant role in the audit. It doesn’t obligate the eventual winner to including the failed candidate in the eventual ‘unity’ government, nor does it detail what happens if, after six months, the unity government unravels.

More fundamentally, the audit may still not tell us which candidate actually won the second round of the election.

Even with the audit process, there are likely so many flaws that no one will ever know whether Ghani or Abdullah ultimately won. That will undermine participatory democracy in Afghanistan and, while the Kerry deal, if successful, will provide greater stability to Afghanistan in 2014, it risks Afghanistan’s long-term commitment to democracy. What happens in the 2019 election, for example, when the Afghans don’t have John Kerry to sort out its mess? Will 2019 elections actually even take place?

Remember that the 2014 debacle follows an even larger fiasco following the 2009 elections. Five years ago, after international observers agreed that the first round was riddled with fraud in favor of the incumbent Hamid Karzai, the US government and others essentially forced Karzai to compete with Abdullah in a runoff. Abdullah dropped out of the race days before the runoff was to be held in protest, ending the crisis over the election, but leaving the democratic process in shambles.

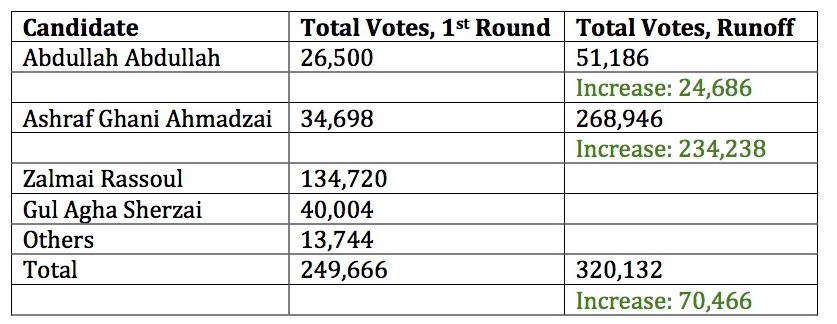

It’s worth taking a moment to examine the arithmetic of the two elections, on the basis of the Afghanistan election commission’s own results:

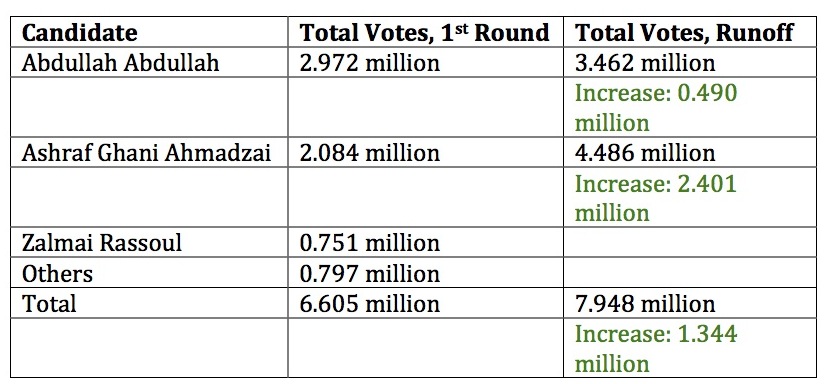

In the first round, Abdullah won 2.972 million votes, Ghani won 2.085 million, Rassoul won 751,000, and other (exclusively Pashtun) candidates won 797,000 — for a total of 6.605 million votes.

The second round turnout amounts to 7.948 million votes, which marks an increase of 1.344 million voters between the April 5 round and the June 14 runoff. That’s believable enough, because more voters, especially Pashtun voters, may have believed the runoff vote was more important than the initial election. With relatively little Taliban and other insurgent violence to disrupt the first round, some voters may have also believed that participating in the June 14 was safer.

In the runoff, Abdullah won 3.462 million votes, an increase of just 490,000. Ghani, on the other hand, won 4.486 million votes, an increase of 2.401 million votes.

There are, roughly speaking, three reservoirs of potential Ghani support in the runoff: (1) Rassoul voters, (2) supporters of the other candidates (the most important of which is insurgent mujahideen leader Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, who was once close to Osama bin Laden), and (3) the supposedly new voters who who participated only in the runoff. That’s a vote bank of around 2.892 million votes. Sure enough, that corresponds to the aggregate increases in both the Ghani and Abdullah runoff vote totals (2.891 million votes).

Among those three groups, Ghani won 83.05% of the vote. In other words, among the 2.892 million voters who didn’t vote in the first round or who voted for a candidate other than Ghani or Abdullah, more than four in five selected Ghani over Abdullah in the runoff.

It’s not impossible, if you believe that:

- Rassoul voters, who are chiefly Karzai supporters more than Rassoul partisans, largely ignored Rassoul’s endorsement of Abdullah and voted for Ghani out of solidarity with fellow Pashtuns;

- the supporters of minor candidates are largely Pashtun voters and less inclined to support the half-Tajik Abdullah in any event; and

- the bulk of the ‘new’ voters in the runoff were Pashtuns who, anxious with Abdullah’s first-round success, moved to support Ghani in the runoff to prevent a candidate chiefly identified with the Tajiks from winning control of Afghanistan’s government.

That’s a convincing enough narrative, but it doesn’t explain everything.

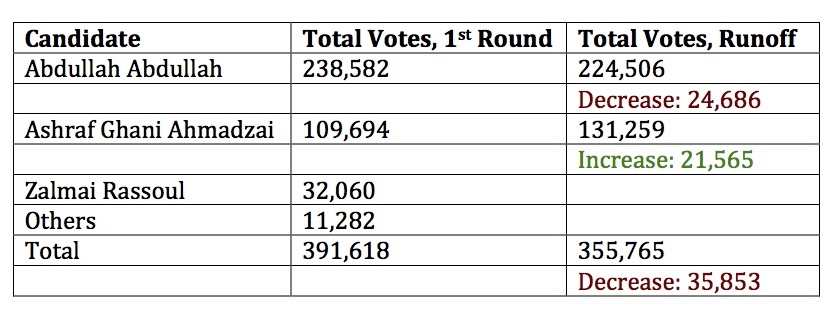

In Kabul province, for example Ghani won nearly 86.3% of those three groups of voters (i.e., Rassoul supporters, supporters of other candidates and new voters), That’s even more surprising, in light of the fact there are more Tajiks in the city of Kabul than Pashtuns:

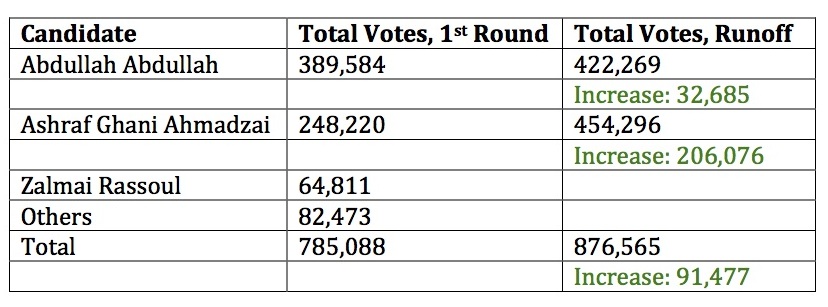

In the far western province of Herat, the second-most populous after Kabul, and another province where Tajiks comprise the largest ethnic group, Ghani won around 84.3% of those three groups:

Notably, Ghani placed fourth in the first round, behind Rassoul and former mujahideen leader Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, the insurgent leader and former bin Laden ally.

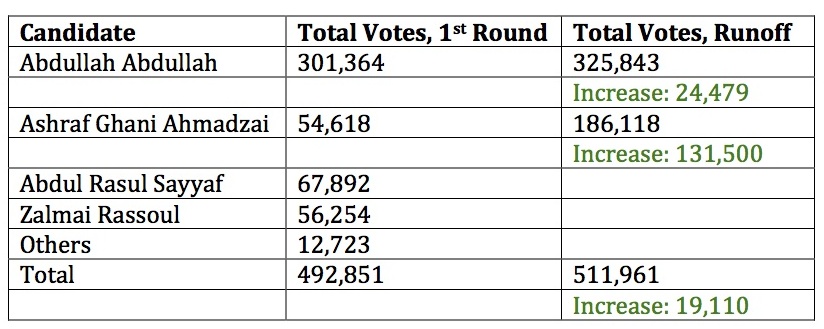

In southern Kandahar province, the only province that Rassoul won, Ghani won an astounding 90.4% of the votes of those three groups:

What’s even more interesting is that in a handful of Tajik-dominated provinces, the surge in turnout wasn’t nearly as strong (i.e., in northeastern Badakhstan was just 5.9% higher in the runoff than in the first round). In some provinces, such as the Tajik-strong Balkh province, turnout dropped precipitously:

Moreover, if you look to the areas of the country where Ghani won some of his strongest victories in the first round, one of those areas includes six eastern provinces that border the mountainous, lawless border between Afghanistan and Pakistan:

Those six provinces (pictured above on the map in red along Afghanistan’s eastern border) — Nangarhar, Paktika, Paktia, Khost, Logar, and Kunar — all saw much higher rates of turnout in the second round, and Ghani netted nearly 1 million votes from those six provinces alone, and that accounts for almost 97% of the the runoff margin between the two candidates:

Of course the audit may well explain why around 97% of Ghani’s margin of victory comes from six provinces bordering Pakistan, or why new voters (and supporters of other candidates) broke by an overwhelming margin for Ghani — over 83% nationally, over 86% in Kabul province, over 84% in Herat province and over 90% in Kandahar province.

Even if you believe the narrative above about why Ghani’s vote totals increased so dramatically between April and June, it’s still hard to escape the nagging doubts that the election results are highly suspect. There’s no guarantee that the Kerry deal will ultimately uncover the truth about those suspect votes, and the Kerry deal doesn’t even try to repair the underlying problems.

At best, it’s a deal to get Afghanistan through a peaceful transfer of power and not necessarily much more. In a world where US troops are rapidly drawing down after 13 years of occupation, and in a world where Afghanistan needs as strong a central government as possible to combat (or, more likely, negotiate with) the Taliban, that’s certainly a positive step. But it’s not a great turn of events for Afghanistan’s long-term health as a democracy or as any kind of functioning state.

We are the largest tv repair service provider in bangalore please visit our website to connect us.