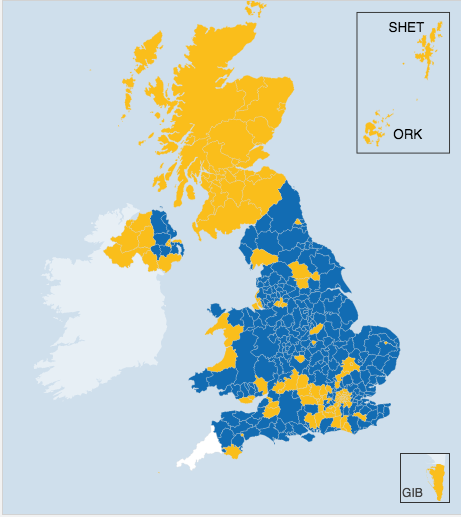

It was first set of regional elections in the United Kingdom since Brexit. ![]()

![]()

But the impending conundrum of Brexit’s impact on Northern Ireland — the future of vital EU subsidy funds and the reintroduction of a land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland that had become all but invisible within the European Union — wasn’t the only issue on the minds of Northern Irish voters when they went to the polls last Thursday.

The snap election followed a corruption scandal implicating first minister Arlene Foster — leader of the pro-Brexit Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) — that caused then-deputy first minister Martin McGuinness to resign from the power-sharing executive, forcing new elections, just 10 months after the prior 2016 elections.

* * * * *

RELATED: Why Northern Ireland is the most serious

obstacle to Article 50’s invocation

* * * * *

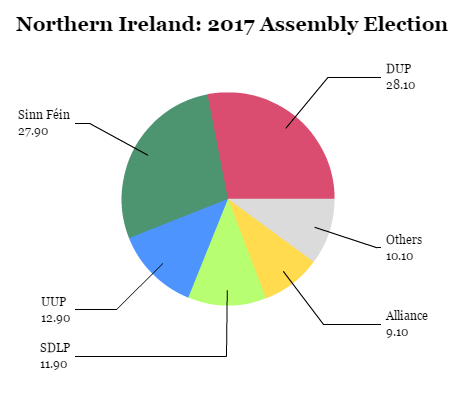

Politics in Northern Ireland runs along long-defined sectarian lines. Most of the region’s Protestant voters support either of the two main unionist parties — the socially conservative and pro-Brexit DUP or the more moderate Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), which backed the ‘Remain’ side in last June’s Brexit referendum. Most of the region’s Catholic voters support either of the two republican parties — the more leftist Sinn Féin or the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), both of which are fiercely anti-Brexit. An increasing minority of voters, however, support the non-sectarian, centrist and liberal Alliance Party.

Since the late 1990s, when the Blair government introduced devolution and a regional parliament at Stormont, and when the DUP and Sinn Féin displaced the UUP and the SDLP, respectively, as the leading unionist and republican parties, the DUP has always won first place in regional elections. That nearly changed last Thursday, as Sinn Féin came within just 1,168 votes of overtaking the DUP as the most popular party.

It leaves the DUP with just one more seat than Sinn Féin and below the crucial number of 30 that it needs to veto policies. Without 30 seats, the DUP will no longer be able to block marriage equality (Northern Ireland lags as the only UK region that hasn’t permitted same-sex marriage) or an Irish language bill that would give Gaelic equal status with English in public institutions. It was high-handed for Foster — and Peter Robinson before her — to block the popular will on both of those issues over the last decade. That, in turn, is not helping the DUP in its bid to negotiate a new power-sharing deal with Sinn Féin.

More consequentially, it leaves unionists with a clear minority for the first time since devolution — just 40 seats in the 90-seat parliament (the number of deputies dropped from 108 members for the 2017 election). Most crucially of all, the election result creates a new equilibrium for the post-election talks between the DUP and Sinn Féin, which are now one week into a three-week deadline to form a new power-sharing executive, as guided by the British government’s secretary of state for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire. Continue reading Northern Ireland struggles to form government after close vote