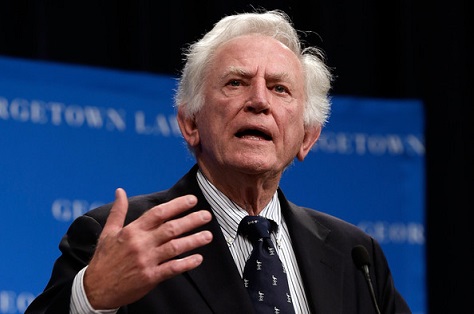

US secretary of state John Kerry appointed former Colorado senator and one-time presidential candidate Gary Hart as the latest US envoy to Northern Ireland’s five-party peace talks earlier today.![]()

![]()

![]()

Nearly two decades after former US senator George Mitchell concluded the Good Friday Agreement, bringing a tenuous peace between republican Catholics and unionist Protestants across Northern Ireland, Hart’s role will not amount to midwifing a landmark peace deal — it will be ensuring its continued implementation:

Fresh negotiations involving the five parties in the power-sharing mandatory coalition convened by the UK Government commenced last Thursday and are due to resume tomorrow.

As well as the long-unresolved peace process disputes on flags, parades and the legacy of the past, over the coming weeks politicians will also attempt to reach consensus on rows over the implementation of welfare reforms in the region and on the very structures of the devolved Assembly.

Northern Ireland is thriving today, amid a growing economy in the long-troubled capital of Belfast. Peace has brought with it a rising standard of living. But, as was on full display upon the death of former Northern Irish first minister Ian Paisley last month, long-simmering tensions still exist. It’s possible, though far from probable, that the kind of widescale violence of the ‘Troubles’ will return to Northern Ireland anytime soon.

* * * * *

RELATED: No eulogies for Paisleyism

* * * * *

It’s great to see Hart — at long last — providing useful service to his country. But US envoys to Northern Ireland today are all destined to be cast as relief pitchers in comparison to Mitchell’s role in shepherding the historic 1998 accords.

For someone who was, to a person, the most prescient voice on homeland security and the threat of terrorism in 1990s, his high-profile turn as a US envoy represents a bittersweet return to public life. Hart’s second act should have started long before age 77.

In the late 1990s, Hart co-chaired the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century — the so-called ‘Hart/Rudman Commission’ — that warned that the US homeland would become vulnerable to attacks, that new technologies could increase US vulnerability, and national borders and the very concept of national sovereignty will erode in the face of growing globalization. The report reads like a prologue to virtually everything that’s followed — from the September 2001 terrorist attacks to the failure of the Rumsfeldian ‘light footprint’ in the US war in Iraq, from the Syrian civil war and use of chemical weapons there to the rise of global cyberterrorism threats, from the return of a more multipolar world order to the stubborn role that energy markets continue to play in shaping foreign policy.

He was ahead of his time as a senator too, leading the way for environmental precautions against nuclear energy disasters and working on legislating relating to intellectual property.

Everyone knows (or should know) the story of Hart’s rise and fall, and it’s a disservice to him to dredge it all up again here. Suffice it to say that Hart, a tough-talking Westerner, represented the kind of ‘new’ Democrat that bridged the peacenik wing of the Democratic Party (he served as South Dakota senator George McGovern’s campaign manager in the 1972 presidential election) and the ‘third-way’ centrism of Bill Clinton, who would eventually win the presidency after Hart’s exit from national political life.

Northern Ireland has its own parliament today at Stormont, where a power-sharing arrangement gives both Catholics and Protestants a role in government. First minister Peter Robinson, of the Protestant-based Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), works alongside deputy first minister Martin McGuinness of the more leftist, Irish republican and Catholic-based Sinn Féin. Three other parties currently in government, the center-left, Irish nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), the center-right Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the non-sectarian, moderate Alliance Party, are also taking part in the talks.

The UK government’s Northern Irish secretary, Conservative minister Theresa Villiers, is chairing the talks among the five parties, and British prime minister David Cameron and Irish taoseaich Enda Kenny, are monitoring the talks closely.

I’m sorry that this venerable Statesman is being wasted, languishing in the doldrums of Northern Ireland’s paltry political problems. However this is not because I feel he deserves better, but because for the life of me I cannot figure out what US involvement can bring to the table. I seem to remember one act of terrorism on US soil circa September 2001 that was the justification for at least one war and countless civilian deaths. It then comes to mind an organisation called NORAID existed. Your own government recognized NORAID engaged in raising funds for the IRA in the US amongst Irish ex-pats. So on one hand the US went to war for one act of terrorism on American soil, and on the other hand US citizens funded countless acts of terrorism in Northern Ireland. If we were to follow the US example of revenge and retribution the Troubles would go on indefinitely. In 1998 Northern Ireland considered the US as having something to bring to the table, now it has absolutely no political traction in this process of peace and reconciliation and we kindly request that the US government keep their noses out. Thanks.