With so many other economic issues to discuss in the South Korean presidential campaign, relations with North Korea had not always been at the forefront of the campaign debate, even though it was always more likely than not that the unique foreign relations challenge will eventually rise to the forefront of the next South Korean president’s agenda in the next five years.

North Korea’s unpredictable passive-aggressive policy with respect to its southern neighbor has continued at a low hum since Kim Jong-un (pictured above) assumed leadership of the ironically named Democratic People’s Republic of Korea following the death of his father, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011.

Today, however, North Korea may have ‘launched’ itself into the presidential race by firing a rocket — literally, a long-range rocket that threatens to make North Korea a dominant issue in the presidential race:

Such developments can influence whom people will support when they go to cast their ballots, although its effects on public sentiments has yet to be determined.

“Experts are divided on the impact, with some predicting the launch will give credence to hardliners and help conservative presidential hopeful Park Geun-hye, while others said people may vote for Moon Jae-in of the liberal opposition party because they do not want an escalation of tensions,” an election watcher said.

He added that because voters are already split between the conservative and liberal camps, the latest provocation by Pyongyang may not really affect the outcome of the race.

“The country as a whole has become ‘indifferent’ having already seen the North test numerous rockets and detonated two nuclear devices,” the expert said. He added that because the launch had been expected people will be less likely to be moved.

For now, with a final presidential debate scheduled for Dec. 16, and with new polls forbidden from publication after Thursday under South Korean election law, it will remain unclear what impact the North Korean rocket launch might have on the campaign until election day.

Ultimately, however, both major candidates in the South Korean election have promised a more conciliatory policy with North Korea than outgoing South Korean president Lee Myung-bak, and many observers believe the rocket launch had more to do with internal North Korean politics than anything else.

While South Korea, with around 50 million people, has a GDP per capita of around $32,000, North Korea’s GDP per capita is something more like $2,400, despite the fact that it has just under 25 million people. The South Korean economy exceeds $1.15 trillion to just around $45 billion in North Korea (see below a photo of the two Koreas at night from the Earth’s atmosphere).

South Korea split from North Korea after World War II, and the Korean War that began in June 1950 when the North invaded the South ultimately became the first proxy battle of the Cold War, pitting active forces from the United States against Communist forces (with the People’s Republic of China backing the North). Despite an armistice agreement in 1953, the two Koreas have formally been in a state of war ever since, and the de-militarized zone between the two marks one of the most heavily armed borders in the world.

While it’s expected that the candidate of Lee’s party, Park Geun-hye of the Saenuri Party (새누리당 or the ‘Saenuri-dang’) would take a more hawkish tone, and Roh’s former chief of staff, Moon Jae-in, the presidential candidate of the liberal Democratic United Party (민주통합당, or the ‘Minju Tonghap-dang’) is expected to pursue a renewed variant of the once-ascendant ‘Sunshine Policy,’ the reality may well be more complicated.

Park has advocated what she uniquely calls a ‘trustpolitik‘ policy toward North Korea — more hawkish, perhaps, than previous policies of the Roh and Kim administrations, but decidedly more geared toward discussion and conciliation than the Lee administration, which Park says has failed to stem the aggression of North Korea.

Given the widespread disillusionment with the Sunshine Policy and its perceived lack of results, in addition to the relatively tighter economic conditions in South Korea, it seems unlikely that Moon would either be willing or able to pursue as wide a conciliatory policy to North Korea as the Roh and Kim administrations.

Lee has taken a hawkish attitude toward North Korea, ending the so-called ‘Sunshine Policy’ of his predecessors Roh Moo-hyun and Kim Dae-jung that had been South Korea’s policy for a decade. Indeed, former president Kim won a Nobel Peace Prize for the policy, which resulted in summits in 2000 and 2007 to discuss further north-south cooperation in greater Korea, but mixed or negative results otherwise. Continue reading North Korea launches itself into top echelon of issues in Korean presidential race →

![]()

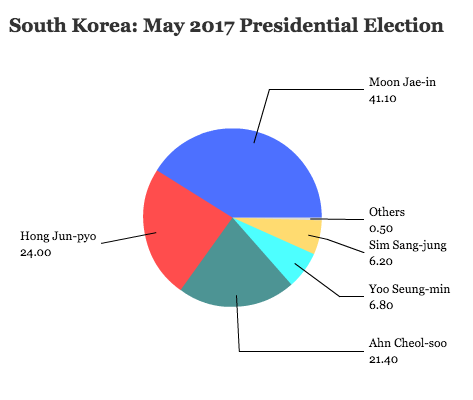

The election marks the end of nearly a decade of conservative rule in the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential office, and Moon has promised to bring a sweep of transparency and reform to domestic policy and a more conciliatory approach to North Korea in foreign policy.

The election marks the end of nearly a decade of conservative rule in the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential office, and Moon has promised to bring a sweep of transparency and reform to domestic policy and a more conciliatory approach to North Korea in foreign policy.