Italian politics just got a lot more complicated.![]()

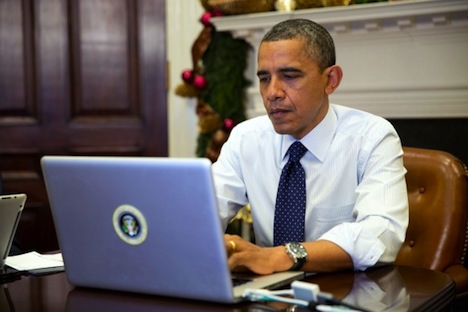

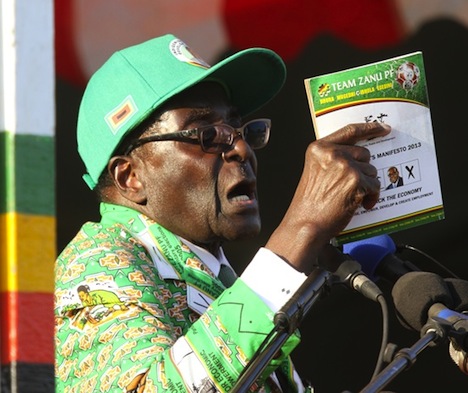

Over the weekend, former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, the leader of Italy’s largest center-right party, Forza Italia, and Matteo Renzi, the leader of Italy’s largest center-left party, the Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), joined forces (pictured above) to introduce the blueprint for a new electoral law.

Notably, the deal didn’t include input from prime minister Enrico Letta, a moderate who leads a fragile ‘grand coalition’ government that includes not just his own Democratic Party, but centrists close to former technocratic prime minister Mario Monti and one of Italy’s two main center-right blocs, the Nuovo Centrodestra (NCD, the ‘New Center-Right’), led by deputy prime minister and interior minister Angelino Alfano. The Alfano bloc split two months ago from Berlusconi’s newly rechristened Forza Italia, which pulled its support from the Letta government at the same time.

The deal is a political masterstroke by Renzi because it makes him appear to have stolen the initiative from Italy’s prime minister. Letta formed a government in May 2013 with the two priority goals of passing a new election law and deeper economic reforms. Despite a ruling in December 2013 that Italy’s current elections law is unconstitutional, Letta’s government has not yet put forward an alternative acceptable to the three main groups in the coalition. So the Renzi-Berlusconi deal is now the only concrete proposal — it backs up the talk that Renzi, the 39-year-old Florence mayor, will be a man of action in Italian politics. Renzi won the party’s leadership in a contest in November 2013 over token opposition. Renzi is neither a minister in Letta’s cabinet nor a member of the Italian parliament, and he’s been more of a critic of the current government than a supporter of a prime minister who until recently was the deputy leader of Renzi’s own party.

By way of background (those familiar can skip the following three paragraphs):

Italy has gone through a few different electoral systems, but most of them have featured either closed-list or only partially open-list proportional representation. Reforms in 1991 and 1993 transformed the previous system in what’s informally been called Italy’s first republic, which spanned the postwar period until the collapse of the dominant Democrazia Cristiana (DC, Christian Democracy) in a series of bribery and corruption scandals collectively known as Tangentopoli (‘Bribesville’). But the current system dates to 2005, when Berlusconi ushered in a new law that everyone (including Roberto Calderoli, who introduced the 2005 legislation) now agrees is awful and which Italy’s Corte costituzionale has now invalidated.

The current law, which governed Italy’s elections in 2006, 2008 and 2013, provides for a national proportional representation system to determine the 630 members of the lower house, the Camera die Deputati (Chamber of Deputies). The party (or coalition) that wins the greatest number of votes nationwide wins a ‘bonus’ that gives it control of 55% of the lower house’s seats, not unlike the Greek electoral system. But the 315 members of the upper house, the Senato (Senate), are determined on a regional PR basis — the top party/coalition in each of Italy’s 20 regions wins 55% of the region’s seats. That means, however, that one party/coalition can hold a majority in the lower house, but wield much less than a majority in the upper house.

That’s the exact situation in which Italy found itself after the February 2013 elections, when the Democratic Party and its allies in the centrosinistra (center-left) coalition narrowly edged out Berlusconi’s centrodestra (center-right) coalition. Beppe Grillo’s protest Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) followed closely behind in third place. It meant that while the Italian left controlled the Chamber of Deputies, it couldn’t muster a majority in the Senate. After a three-month political crisis that ended with the inability to elect a new Italian president (Italy’s parliament ultimately decided to reelect the 88-year-old Giorgio Napolitano to an unprecedented second seven-year term), the Democratic Party’s leader Pier Luigi Bersani resigned, and Napolitano invited Letta to form Italy’s current government.

The Renzi-Berlusconi deal sketches out an electoral reform on roughly the following lines:

- The Chamber of Deputies would become, by far, the predominant chamber of Italian lawmaking. The Senate would hold fewer powers as a region-based chamber. Italy’s national government would also consolidate more powers away from Italy’s regions.

- Deputies would be elected, as they are now, on the basis of national, closed-list proportional representation, which concentrates power in the hands of party leaders and elites (as opposed to open-list, which would allow voters to choose the members that represent them in parliament). An alternative might be something akin to the proportional aspect of the Spanish electoral system — in Italy, it would mean a proportional system divided into 118 constituencies, each of which elects four or five deputies.

- If a party/coalition wins over 35% of the vote, it will still yield a ‘majority bonus’ of either 53% or 54% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies. If no party/coalition wins over 35%, the top two parties/coalitions will hold a runoff to determine who wins the majority bonus.

- Italy would introduce a threshold for parties in order to reduce the fragmentation of Italy’s politics — a party running outside a coalition would need to win 8% of the vote and a party running inside a coalition would need to win 4% or 5% of the vote running outside a coalition (though the thresholds would be much lower in a multi-district ‘semi-Spanish’ system).

- The deal would not replicate the French system, which elects legislators to single-member districts in a two-round election, and which has been discussed often as an alternative for Italy.

The details are not so important at this stage, because they could change as the Renzi-Berlusconi deal begins the long process of turning into legislation. But if Renzi can pull the majority of the Democratic Party along, and if Berlusconi’s Forza Italia supports the deal, the two groups could steamroll Italy’s smaller parties, even in the Senate. If Alfano and his bloc joins, the deal would be unstoppable. Renzi has already won a majority of the party’s executive committee (a promising first sign), and Alfano has indicated that he’s open to the reform (though less excited about closed lists).

But there are all sorts of fallout effects — politically, legally and electorally — to contemplate over the coming days and weeks. Continue reading Renzi, Berlusconi team up for electoral law pact