Chile’s general elections on Sunday went just about as much as expected.

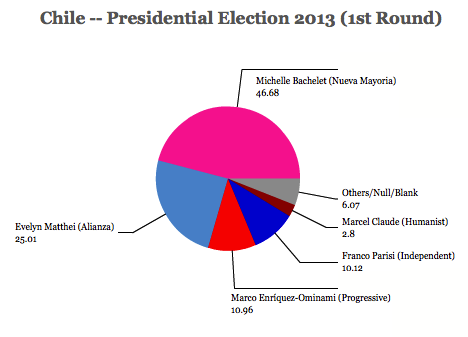

Michelle Bachelet leads all over candidates by a margin of over 20%, but with just 46.68% support, she’ll narrowly miss the absolute majority that she needs to avoid a December 15 runoff. Bachelet, who served as Chile’s president between 2006 and 2010, is the candidate of the Nueva Mayoria (New Majority) coalition, which is itself based on the broad center-left Concertación that’s won four out of the five past elections since the return of regular democracy in Chile in the late 1980s after the regime of Augusto Pinochet.

In second place, also as widely expected, is Evelyn Matthei with 25.01% — Matthei is a former senator and a former minister of labor in the administration of outgoing center-right president Sebastián Piñera, who is the candidate of the broad center-right coalition that’s comprised of Piñera’s Renovación Nacional (RN, National Renewal) and Matthei’s more conservative Unión Demócrata Independiente (UDI, Independent Democratic Union).

But given how close Bachelet came to winning an outright majority, she is almost assured of victory against Matthei in the second round — so the next four weeks of campaigning will likely amount to somewhat of a victory lap for Bachelet, who hopes to become the first former Chilean president to return for a second, non-consecutive term in recent history.

It’s been a difficult year for Chilean conservatives — its center-right coalition, the Coalición por el Cambio (Coalition for Change), widely known as the Alianza por Chile (Alliance for Chile), which saw its frontrunner for president, former energy minister Laurence Golborne withdraw from the race in the spring due to accusations of malfeasance stemming from his time in the private sector, and which saw its elected presidential nominee, former economy minister Pablo Longueira, withdraw promptly after winning the hard-fought nomination on account of clinical depression.

Surprisingly far behind in third place were two relatively independent candidates.

Marco Enríquez-Ominami (popularly known as ‘MEO’), ran a stridently leftist campaign as the founder and leader of the Partido Progresista (Progressive Party), and he hoped to improve on his performance in the December 2009 first-round presidential election, when he won 20% of the vote. Instead, he won just 10.96% of the vote, a disappointment for Enríquez-Ominami’s feisty campaign and the sign that the broad center-left electorate largely coalesced around Bachelet’s candidacy.

Perhaps even more disappointing was the performance of Franco Parisi, who won just 10.12% of the vote — an independent center-right candidate, Parisi was vying for second place in polls with Matthei a month ago before Matthei started attacking Parisi, a popular professor and economist, especially with regard to allegations that he withheld $200,000 of employee wages.

While Bachelet may have enjoyed winning the presidency outright, more important to her and the Nueva Mayoria coalition are the results of the parliamentary elections also held on Sunday — Chileans were electing all 120 members of the Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies), the lower house of Chile’s parliament, and a little over one-half of the 38-member Senado (Senate), the upper house.

With just over 95% of the vote counted for the Chamber of Deputies, the center-left Nueva Mayoria held 65 seats, the center-right Alianza held 47 seats, with four seats still undecided, and with one seat going to the Progressive Party and three seats going to independents, leaving Bachelet and the center-left on the cusp of winning the 69 seats necessary for a four-sevenths majority in the lower house, which is necessary to enact the kind of major educational and tax reforms that Bachelet hopes to pass in the next four years, but not the two-thirds majority necessary for constitutional revisions. Under Chile’s ‘binomial’ system, however, in which two deputies are elected from each of 60 districts, it’s difficult to achieve a lopsided victory in either direction in either house of parliament.

In the Senate, of the 20 seats up for election, the Nueva Mayoria has won 12, the Alianza just six, with one independent and one still to be determined. Given that the other 18 Senate seats divided between nine for the center-left and nine for the center-right in the previous December 2009 election, that would give Nueva Mayoria at least 21 seats in the Senate and the Alianza 15 — enough for a clear majority, but again just on the cusp of winning a four-sevenths majority (22) in the upper house as well.

As Duke University professor Ariel Dorfman wrote in The Guardian over the weekend, the two were once childhood playmates when their fathers both served in the Chilean air force — Matthei’s father supported Pinochet in the September 1973 coup against president Salvador Allende, while Bachelet’s father opposed the coup and was subsequently imprisoned, tortured and died in prison in 1974:

Fernando Matthei was a military attache at the London embassy when the coup led by Augusto Pinochet destroyed Chilean democracy. He could do nothing to help the friend with whom he used to exchange classical records and talk into the night about sports, politics and literature. But his failure to act could no longer be justified, however, when he returned to Santiago at the end of 1973 and was named director of the aviation’s War Academy – the very building in which Alberto Bachelet was to die two months later. Though several judicial reviews and trials found that then Colonel Matthei had no penal culpability in the death of General Alberto Bachelet – the cellars where his comrade-in-arms were being tormented were off limits to anyone not working as an interrogator – the guilt still haunts him. In his 2009 book, he admitted: “Prudence outweighed courage.”

Not even the most delirious novelist could have imagined a more unusual history of differing destinies. One dies because he had the courage, though perhaps not the prudence, of accepting to head the distribution and food centre of Allende’s government, a post that had ministerial status. The other lives a life of excessive prudence and no courage and is ultimately named to the ruling junta. General Matthei also served as health minister in Pinochet’s cabinet – a portfolio that Michelle Bachelet held a generation later. As for Evelyn Matthei, she was a senator and then labour minister in Piñera’s government. A study in contrasts: the socialist who became Chile’s president and the conservative who aspires to that presidency.

Bachelet and her family sought exile in Australia and East Germany, and Bachelet returned to Chile only in 1979 as a pediatrician.

Third-place candidate Enríquez-Ominami’s father, a revolutionary leftist who also opposed the coup, was also executed by the Pinochet regime, and the effect demonstrates just how much the ghosts of 1973 (and the ghosts of the Pinochet regime, which governed until 1989) haunt contemporary Chilean politics.

Continue reading Chilean parliamentary and presidential (first round) election results →

![]()