The results are in, and Scotland did not vote yesterday to become a sovereign, independent country.![]()

![]()

Scottish residents — and all British citizens — will wake up today to find that, however narrowly, the United Kingdom will remain as united today as it was yesterday, from a formal standpoint.

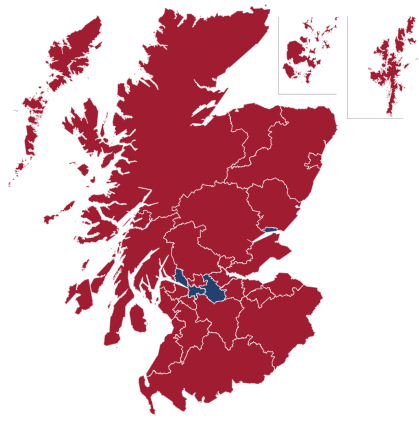

With all 32 local councils reporting, the ‘Yes’ camp has won 1.618 million votes (44.7% of the vote) against 2.002 million votes (55.3% of the vote) in favor of remaining within the British union, capping a 19-month campaign that resulted in a staggering 84.6% turnout in Thursday’s vote.

Moreover, ‘Yes’ won four councils, including Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city:

But the close call has shaken the fundamental constitutional structure of the United Kingdom, and Scotland’s vote will now dominate the political agenda in the final eight months before the entire country votes in a general election next May, for better or worse.

So who comes out of the referendum’s marathon campaign looking better? Who comes out of the campaign bruised? Here’s Suffragio‘s tally of the winners and losers, following what must be one of the most historic elections of the 2010s in one of the world’s oldest democracies.

The Winners

1. Scottish nationalism

The nationalists lost Thursday’s referendum. So why are they still ‘winners’ in a political sense? Continue reading Scottish referendum results: winners and losers