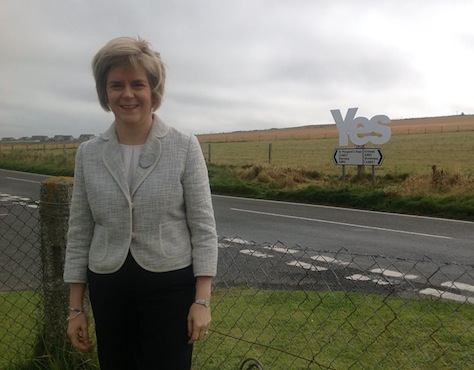

If there’s one person who will benefit no matter how Scotland votes in its too-close-to-call independence referendum on September 18, it is deputy first minister Nicola Sturgeon, who has taken a high-profile role leading the ‘Yes’ campaign that supports Scottish independence.![]()

![]()

When Alex Salmond, the leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP) became first minister in May 2007, just eight years after Scotland’s initial elections for its local parliament in Holyrood, Sturgeon became his deputy, and she has served as the deputy leader of the SNP since 2004.

* * * * *

RELATED: How an independent Scotland could enter the EU

* * * * *

If Salmond suffers a defeat in next week’s referendum, the 44-year-old Sturgeon, a popular figure in Scotland, might soon replace the 59-year old Salmond in government. Some SNP deputies are already arguing that, if the ‘Yes’ camp doesn’t win next Thursday, Salmond should resign and allow Sturgeon to become first minister, in much the same way that Tories in Westminster are arguing that British prime minister David Cameron would have to step down if the ‘Yes’ campaign wins.

With polls now showing that the ‘Yes’ campaign has essentially caught up with the ‘No’ campaign, a close defeat may yet be a victory for Salmond. As in Québec in 1980, a narrow loss wouldn’t foreclose another possible vote in a decade’s time. But it might be difficult, after losing Scotland’s best chance at independence, for Salmond to lead the SNP into a campaign for a third consecutive term in the next elections, which must be held before 2016. Moreover, another term as first minister is a letdown from the much headier notion of becoming sovereign Scotland’s first prime minister.

On the other hand, if the ‘Yes’ camp pulls off the victory that just a week ago seemed out of its grasp, Sturgeon would almost certainly rise to deputy prime minister in an independent Scotland, just as much the heir apparent to Salmond then as now. As women flock toward independence, according to many polls, Sturgeon may be the ‘Yes’ campaign’s secret weapon.

The bottom line is that Sturgeon is the favorite to become, within the decade, either Scotland’s next first minister (within the existing UK system) or its second prime minister as an independent country.

In light of all of the questions — including Scotland’s currency and EU membership — that would be settled in its first chaotic years as an independent nation-state, Scotland’s future leadership is one of the key variables in whether it would become viable as a new state.

So what exactly would Sturgeon bring in the way of political skill and states(wo)manship?

She’s been a Scottish Nationalist activist since her youth, and her husband, Peter Murrell, is the SNP’s chief executive and a leading campaign strategist.

Sturgeon is generally to the left of Salmond, who began his first decade-long stint leading the SNP in 1990, at the end of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government and seven years before the Labour government of Tony Blair introduced a referendum on devolution. Sturgeon, who served as Scotland’s minister for health between 2007 and 2012, would pull an independent Scotland in a more social democratic direction, with higher taxes, higher services and a relatively more dovish foreign policy than the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, she has earned deserved praise both in Scotland and England for her political skill and thoughtfulness on policy.

Though there are real differences between Salmond and Sturgeon on both substance and style, their relationship has matured in a much different way than the famously acrimonious relationship between two Scottish-born Labour prime ministers, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown:

The result of the Salmond/Sturgeon partnership has been an extended period of darkness for the Labour party in Scotland, which began with the SNP grabbing power in 2007 and then making themselves unassailable in 2011 with the majority that paved the way for the independence referendum. There are no visible signs of any recovery from Labour in Scotland.

Sturgeon is from a younger generation, but still one that entered nationalist politics without much hope of gaining true power:

Joining the SNP in the 1980s was not about having a career in politics, Sturgeon explained to the playwright David Greig, host of that recent fringe event. “There’s a generation now getting involved who do expect the prospect of getting elected and being in government. My generation come into this purely out of conviction.” It was this remark that struck Greig in retrospect. “What she seems to be is a bridge between 1950s nationalism, which might be regarded as old-fashioned tweed and tartan SNP, and the modern social democratic SNP that is being forged in Holyrood.”

Either way, Sturgeon’s emergence points to a rise among female leaders in Scotland. Independence or no, Sturgeon would join the Scottish Labor Party’s leader Johann Lamont and the Scottish Conservative Party’s leader Ruth Davidson, a relatively moderate figure who, among other things, supported same-sex marriage last year. Like Sturgeon, both Lamont and Davidson might hope to thrive in an independent Scotland.

Lamont would be rid of the millstone of the Brown government and the plodding national leadership of Ed Miliband, whose polling lead in the May 2015 general election has gradually dissipated. In an independent Scotland, Lamont and Scottish Labour might naturally compete with a newly aimless SNP (having achieved its main goal of independence) for center-left voters.

Davidson would be rid of all the baggage of English Tories, from the toxic Thatcher brand to the Cameron government’s unpopular budget cuts. For all the talk that Scotland could come to resemble the Scandinavian social welfare states, Scotland is essentially a conservative society, and a Scottish Tory brand rinsed clean of four decades of antipathy could rejuvenate conservative Scottish politics.

If the transition from Salmond to Sturgeron were done right, though, and Scotland seamlessly moves into independence, it could secure the SNP in government for a decade or more — and no one would benefit more than Sturgeon.

Sturgeon’s gender hasn’t always been an attribute in a culture of misogynist Scottish politics — her nickname for much of her career was ‘wee nippy,’ a Scottish term for being a confident woman advancing in the rarefied field of government and power.

But as the ‘Yes’ campaign savors the thrill of coming so close to winning next week’s vote, Sturgeon stands ready to gain no matter what the result.