Last weekend, Nigeria — the most populous country on the African continent — should have held its presidential election.![]()

It didn’t, because the government, led by president Goodluck Jonathan, ordered the voting postponed for six weeks, from February 14 to March 28, to give the Nigerian military a little more time to do in six weeks what it hasn’t been able to do in six years — defeat the Boko Haram militants that control part of Borno state in northeastern Nigeria and threaten much more of northern Nigeria and northern Chad. That, in turn, has complicated efforts to provide voter cards to the largest electorate on the African continent.

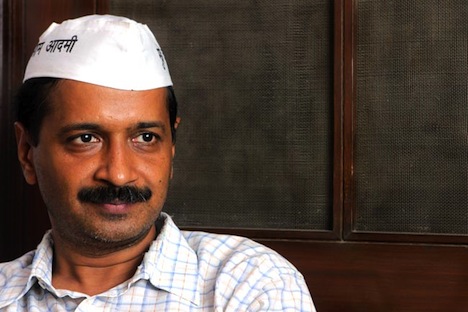

When the government announced the election’s postponement, it looked more like a cynical attempt to buy six more weeks to shore up his campaign for reelection. Though Jonathan (pictured above) is the candidate of the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP), his inability to halt the rise of Boko Haram, and his unwillingness or inability to rein in Nigeria’s endemic corruption have left him vulnerable. Moreover, as a southerner, Jonathan never won over the trust of northern Nigerians. It didn’t help that Jonathan came to power in 2010 with the death of his predecessor, Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, and sought reelection in his own right in 2011. That upset the balance between northern and southern presidents, contributing greatly to the mistrust of Muslim northerners.

* * * * *

RELATED: Nigeria emerges as Africa’s largest economy

* * * * *

Jonathan’s strategy may turn out to backfire, especially if (when?) he doesn’t eradicate the Boko Haram threat before the end of March, when voters may well replace him with his opponent, Muhammadu Buhari. Though Buhari is a northerner and is expected to sweep the Muslim north no matter what happens in the next six weeks, he hardly represents a breath of fresh air to Nigerian voters. He’s running for the fourth consecutive time, and he holds the distinction of having lost the Nigerian presidency not only to Jonathan in 2011, but to Yar’Adua in 2007 and to Olusegun Obasanjo in 2003.

Buhari, like Obasanjo, played a role in the era of Nigeria’s military dictatorships. He served as Nigeria’s leader from December 1983 to August 1985, taking power in a military coup that deposed one of Nigeria’s few elected presidents of the era, Shehu Shagari. Buhari has a reputation for probity and for intolerance of corruption, one of the factors in his own overthrow in 1985 at the hands of Ibrahim Babangida, another military leader — one that Nigerian elites found much more permissive to the widespread graft in government to which they had become accustomed in the 1970s and early 1980s. Though Buhari is, in essence, a three-time loser in the most recent era of Nigerian ‘democracy,’ voters increasingly believe that his military background and anti-corruption credentials could improve a country where fortunes could hardly be worse.

In addition to the Boko Haram threat, simmering ethnic tensions in the north, where 12 states have adopted a form of Islamic sharia law since the early 2000s, and in the southeast, which remains impoverished despite holding much of Nigeria’s oil wealth, threaten national unity. Jonathan and his finance minister, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, have been forced to cut the country’s budget as global oil prices plummeted in the past six months — and as the value of the naira has lost nearly 20% of its value in the same period.

To make matters worse for Jonathan, Obasanjo resigned yesterday officially from the PDP, dramatically tearing up his membership card and excoriating Jonathan’s leadership. It should come as no surprise that Obasanjo is backing away from Jonathan. Obasanjo stepped down in 2007 only after hand-picking Yar’Adua for president and Jonathan for vice president because he thought they would be pliable allies, allowing him to continue to direct Nigerian policy from outside the presidency. Yar’Adua quickly distanced himself from Obasanjo, as did Jonathan, who resisted calls last year from Obasanjo not to run for reelection.

Moreover, Obasanjo has not-so-quietly signaled his enthusiasm for the opposition All Progressives Congress (APC) and for a Buhari presidency. Like Buhari, Obasanjo comes from the military and, like Buhari, he served as a military leader of Nigeria, from 1976 to 1979.

Whereas Jonathan might have hoped an extended campaign would give him time to consolidate his support, it might have the opposite effect, in essence giving Buhari a six-week period of triumphant campaigning. Earlier this week, Buhari traveled to Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, for a rally, despite significant security concerns. It follows a surprise visit earlier this week by Jonathan to the state.

The rise of the APC, a coalition of opposition parties and disaffected PDP leaders, is in one sense good for Nigerian democracy, considering that the PDP has ruled Nigeria since the return of civilian rule in 1999. The risk is that an increasingly desperate Jonathan will try to win the election through fraud, splitting Nigeria on tense north-south lines at a time of economic and security fragility. Though Nigeria has held four consecutive, regular presidential elections, its democracy remains flawed and, according to many observers, deteriorating. Moreover, the Nigerian military, now used to 16 years of PDP rule, may be actively working to prevent a Buhari victory.

Nigeria has sub-Saharan Africa’s largest economy, officially surpassing South Africa last year after recalibrating the way that its government measures GDP growth. It also has the continent’s largest population (173.6 million). So if democratic rule falters, or if Boko Haram grows to the point to destabilizing Nigeria’s already underdeveloped north, it will establish a disproportionate precedent for African governance across the continent. Colonial British administrators artificially joined the chiefly Muslim Northern Protectorate and the chiefly Christian Southern Protectorate in the 1950s prior to the country’s independence in 1960. Today’s disparity in resource allocation in favor of Nigeria’s southeast date back to the colonial era.

Shortly after independence, the country split on tripartite ethnic lines — the northern Hausa-Fulani, southwestern Yoruba and southeastern Igbo — culminating in the Biafra War of 1967-70. Though Nigeria ultimately defeated the southeastern secessionists and took a forgiving stance to post-war reconciliation, the first decade of Nigerian independence strengthened the military, which would come to dominate government for the next three decades. The war also resulted in the geopolitical division of Nigeria into what is today 36 states and its federal capital region of Abuja. While that’s empowered minority ethnic groups, at the expense of each of the three dominant minority groups (Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and Igbo), it has also strengthened the federal government, giving it more respective power over allocating resources from Nigeria’s oil resources — and more opportunity for corruption.