Earlier this month, Nigeria ‘recalibrated’ the way it calculates its gross domestic product to more effectively capture the real value of its economy.![]()

It’s a step that many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are taking — including Ghana in 2010 and Kenya this year — as they refine the tools they use to measure GDP growth. Nigeria, for example, hadn’t recalculated its base since 1990. Perplexingly, e-commerce, telecommunications and the country’s growing film industry (‘Nollywood’) hadn’t previously been captured.

Not surprisingly, the recalibration caused Nigeria’s official GDP to leap by nearly 75% to around $510 billion, making it Africa’s largest economy. That shouldn’t come a surprise to anyone, in light of predictions that Nigeria would overtake South Africa sometime by the end of the decade. Nigeria is the epitome of the newly emerging Africa. Lagos, its sprawling port, is now Africa’s largest city, recently surpassing Cairo. Its population, already Africa’s largest at 173.6 million, could surpass the US population within the next three decades or so.

But Nigeria’s newfound status is more the beginning of a journey than its terminus, a journey that will become especially pertinent to global affairs throughout the 21st century as Nigeria’s impact begins to rival that of China’s or India’s.

But today, Nigeria’s GDP per capita, even after the rebasing, is just around $3,000. That’s less than one-half the level of GDP per capita in South Africa, which is around $6,600. Though the stakes of Nigeria’s relative success or failure will become increasingly important to the rest of sub-Saharan Africa and to global emerging markets in the years ahead, there’s no guarantee that Nigeria, 54 years after its independence, won’t succumb to state failure.

Nigeria spent its first decade stuck in a tripartite ethnic struggle that ended in a devastating civil war, followed by bouts of military rule from which it emerged imperfectly in 1999. Lingering security challenges, like those posed by Boko Haram, a Muslim insurgency from Nigeria’s northeast, continue to expose the country’s ethnic tensions and the religious and socioeconomic gap between the relatively prosperous Christian south and the relatively underdeveloped Muslim north. Incipient political institutions plagued by a culture of corruption for decades, with less than fully formed democratic norms, could easily erase the stability gains made since the 1999 return to democracy. Although oil wealth has since the 1960s given Nigeria a financial means to solve its lengthy list of developmental, educational, and environmental problems, the mismanagement of oil revenues have so far transformed the wealth into a classic resources curse.

Existential challenges

Even before independence, British colonial rule divided what is today’s Nigeria into a Northern Protectorate and a Southern Protectorate, and the two parts of today’s Nigeria were governed, nearly until 1960, as discrete units.

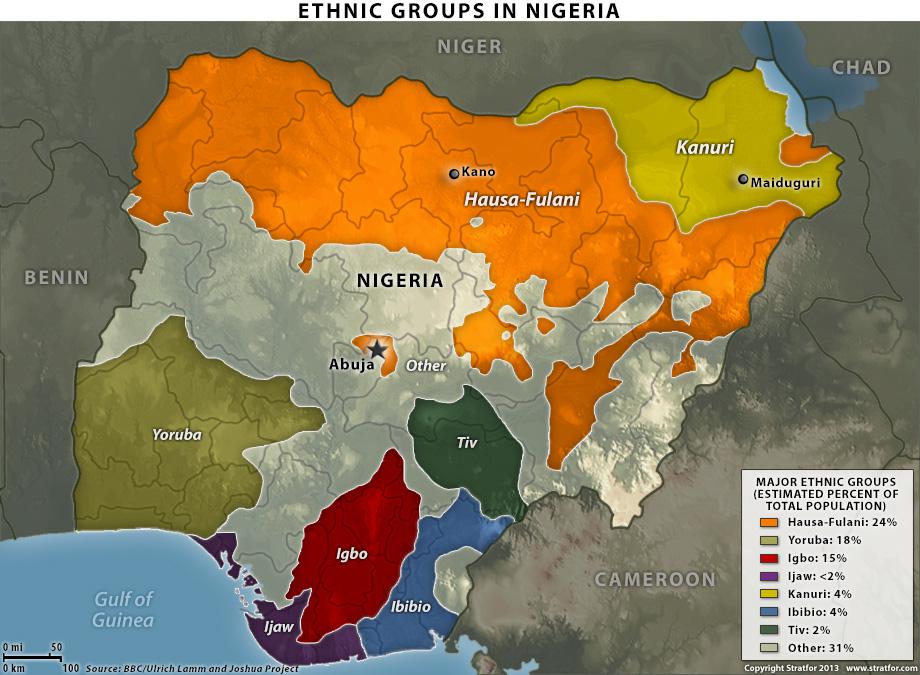

But it’s not quite as simple as the difference between the Muslim north and the Christian south. Nigeria is comprised of dozens of ethnic groups, some of which are only relatively recent constructs from 19th century colonial rule. As in other colonial fiefdoms throughout Africa, the British emphasized sometimes minor ethnic differences through classic divide-and-rule tactics.

In Nigeria today, three ethnic groups largely dominate the country’s north, east and west.

In the southeast, the Igbo group largely dominates, though it’s by no means the only ethnic group in the east. The Igbo embraced some Western traditions, such as education, with the most enthusiasm during the colonial era. Though much of Nigeria’s oil wealth, which was discovered during the colonial era and began production in 1958, comes from the eastern Niger Delta, it’s a subregion within the east where the Efik, Ibibio and Ijaw, among others, outnumber the Igbo.

The Yoruba group is predominant in the southwest of Nigeria, including in and around the port city of Lagos. As in the other major regions, the Yoruba aren’t the only ethnic group within the west.

Roughly speaking, two groups dominated what is today northern Nigeria — the Hausa and the Fulani. The latter, a migratory group from what is today Sudan that pushed westward over time, came to dominate the north so thoroughly in the 19th century that it’s common to speak today of the Hausa-Fulani ethnic group in Nigeria. Both groups share the Sunni Muslim religion and other traditions, and throughout the late colonial area, British authorities provided the Nigerian north, even after both protectorates were united, a large measure of autonomy.

Unfortunately upon independence, that meant that while the northerners comrised a majority (barely) of Nigeria’s population, they lagged far behind in education and other measures of social progress. For a while, under Nigeria’s first president Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigeria’s northerners and easterners co-existed in a wary coalition government, with Hausa-Fulani, Igbo and Yoruba leaders governing each of the northern, eastern and western regions, respectively. A split within the west, however, upset the delicate dynamic, and Nigeria suffered its first coup after just six years, a bloody affair during which the Igbo-dominated military took power.

Though Nigeria’s eventual leader, Yakubu Gowon, wasn’t technically Igbo, he was still a Christian from Nigeria’s ‘middle belt,’ and increasing suspicion in the north led to reprisals and attacks on easterners living in the north. Terrified, easterners throughout the country fled to the Igbo-dominated heartland, and they quickly coalesced under Odumegwu Ojukwu, a military general who declared the east as the independent state of ‘Biafra’ in 1967. The rest of Nigeria, unwilling to let almost all of Nigeria’s oil wealth secede, fought tenaciously over the next three years to reclaim Biafra. Despite the ferocity of Nigeria’s civil war, Gowon quickly re-integrated eastern Nigeria back into the country, largely facilitated through the oil boom of the early 1970s that quickly filled Nigeria’s coffers. Ironically, the Biafran War may even helped bring about a measure of national unity through the joint service of northerners and westerners in the Nigerian armed forces.

After the regional factionalism of the Nigeria’s first decade, its rulers, both civilian and military, quickly divided the country from three regions into 36 states today, plus the capital territory of Abuja. Not only has that reduced the inherently unstable tripartite balancing act among the Hausa-Fulani, Igbo and Yoruba, but it’s given other ethnic groups more autonomy in their own smaller regions.

That doesn’t mean that today’s Nigeria doesn’t have difficulties.

The Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) is a political organization that is fighting for greater economic development and autonomy for the Niger Delta. Ironically, though the region is responsible for much of Nigeria’s oil wealth, its relatively lack of political clout means that it remains one of the more underdeveloped and overpopulated parts of the country. The Igbo group, though a majority in the southeast, is not predominant in the Niger Delta, so it had no particular self-interest in funneling development outside the Igbo-dominated regions of the east. What’s more, the exploitation of the region’s oil deposits have contributed greatly to the region’s environmental degradation. Though it’s a relatively new organization, MEND follows a long tradition of groups that have used sabotage, kidnappings and other political violence to demand economic and social justice for the delta’s residents.

The north, too, has always had its share of differences with the rest of Nigeria. In the early 2000s, 12 northern states introduced shari’a law as the basis for criminal law. Though shari’a has always influenced the resolution of civil and personal disputes, its introduction into criminal law is a new phenomenon. The harsh punishments for what’s called hudud — serious crimes under Islamic law, including not only theft, but adultery, homosexuality and alcohol consumption — are problematic from an international human rights perspective.

Boko Haram, which emerged in 2002, and which today poses the most significant terrorist threat to the Nigerian state, is a fundamentalist group with the mission of building a pure Islamic state governed exclusively by shari’a law. Its motivations are extremely anti-Western, and its name, Boko Haram, in the Hausa language literally means, ‘Western education is a sin.’ The group is thought to be responsible for the bombing of an Abuja bus station earlier this week that killed 71 people, and attacks that have killed nearly 1,500 people this year alone.

So even as Nigeria emerges as global economic force, it’s important to realize that, though it hasn’t devolved into civil war since the late 1960s, the country’s divisions are nonetheless striking.

Political challenges

Nigeria’s political history in the 1960s was brutal, and it was anything but democratic. But what followed over the next 30 years was nearly as bad — and in terms of key personal and political freedoms, the military regimes of the 1980s and the 1990s were even worse.

After winning the Biafran War in 1970, Gowon continued to govern Nigeria, though his government raised the bar for glaring corruption and massive economic mismanagement, even at the height of the Nigerian oil boom. Yet another military coup toppled Gowon in 1975 with a view toward restoring civilian rule. Though the coup’s initial leader, Murtala Muhammed, was assassinated in 1976, his deputy, a Yoruba general named Olusegun Obasanjo succeeded him and kept Nigeria moving toward what would ultimately become the Second Republic — a return to civilian rule with the 1979 presidential election.

Shehu Shagari, a Fulani who narrowly won the presidency within a divided field, faced almost immediate problems — the expectations of corruption within the Nigerian government continued unabated even as global demand for oil collapsed. In 1983, amid deteriorating economic conditions, the military once again took power, and in 1985, Ibrahim Babangida, a northern general, began an eight-year military reign of terror that produced some of Nigeria’s worst human-rights abuses in its post-independence history.

Babangida’s plan to restore civilian rule went awry with the June 1993 presidential election — though Yoruba leader Moshood Abiola was widely acknowledged to have prevailed, the government quickly annulled the results for fear of losing power, and it tried and imprisoned Abiola for treason.

In the face of widespread international and Nigerian condemnation, Babangida resigned. But it took just three months for another northern general, Sani Abacha, to wrest control of the government.

Abacha’s regime made Babangida’s seem relaxed, and his five-year reign was marked by nearly totalitarian control in Nigeria. Far from returning the country to civilian rule, Abacha pulled Nigeria in the other direction. His mysterious death in 1998 (he died, according to media reports, in the arms of two Indian prostitutes), just two weeks before the equally mysterious death of Abiola, still languishing in prison, ultimately launched Nigeria on its current path to its somewhat fragile democracy.

Abacha’s successor, Abdulsalami Abubakar, quickly dismantled Abacha’s regime of terror, and paved the way for the February 1999 presidential election. Obasanjo, now a former general who had served in prison during the Abacha regime, easily won the election under the mantle of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which has controlled both the Nigerian presidency and its bicameral National Assembly for the entire 15 years of Nigeria’s current Fourth Republic. Though Obasanjo is a southerner, he initially came to power through a coalition that included a majority of northerners.

Despite Obasanjo’s role in restoring civilian rule in the 1970s, and his commitment to civilian rule in the 1990s and 2000s, his administration wasn’t necessarily a triumphant success. He won reelection in 2003, despite a vote that featured serious irregularities. Though his administration didn’t rein in much of the country’s notorious corruption, it did oversee the payment of Nigeria’s outstanding debt (at one point in the 1980s, public debt exceeded 140% of GDP) in 2006, which followed the 2005 forgiveness of nearly $23 billion in foreign debt.

Moreover, the Nigerian Senate demonstrated some independence when it rejected Obasanjo’s bid to abrogate constitutional term limits to run for a third consecutive term as president. With the election of the PDP’s Umaru Yar’Adua — this time a northerner — as Nigeria’s new president in 2007, Obasanjo’s administration effected the first civilian transfer of power in the country’s history.

When Yar’Adua disappeared in 2009, amid speculation over ill health, it caused something of a constitutional crisis. When he finally died in 2010, his vice president, Goodluck Jonathan (pictured above), a southerner from the coastal Ijaw ethnic group, took power.

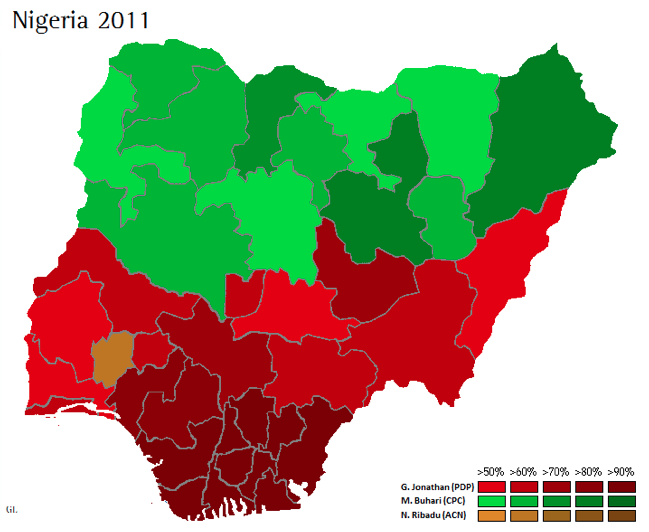

Though Jonathan overwhelmingly won the subsequent April 2011 presidential election as the PDP’s candidate with 58.89% of the vote, it didn’t help matters that a northerner held the presidency for just three years prior to Jonathan’s ascent to the Nigerian presidency, thereby miscalibrating the presidential balance that the northerners expected — two terms for Obasanjo, the southerner, and two terms for Yar’Adua, the northerner.

Making matters worse, Muhammadu Buhari, his chief opponent, overwhelmingly won all the states of Nigeria’s north (Buhari led a brief military government between 1983 and 1985, when he was deposed by Babangida).

That’s caused something of a realignment among Nigeria’s parties. Northern defectors from the PDP, unhappy with the possibility that Jonathan may seek reelection in 2015, joined with Nigeria’s two largest political parties in February 2013 to form a new party, the All Progressives Congress (APC).

While opposition politicians have held many governorships, including the key Lagos state governorship, the APC could pose a challenge to the PDP’s hegemony in 2015 elections — even Obasanjo, who continues to wield significant political power, has flirted with the possibility that he could put his weight behind the new party. Jonathan’s potential reelection bid, further defections from the PDP, Jonathan’s inability (like all of his predecessors) to tamp down corruption and the Boko Haram insurgency could all lead to an APC government early next year.

Though that means greater political competition, which is ultimately a good thing for Nigerian democracy, the transition to a true two-party system in Nigeria could also exacerbate the longstanding regional, religious and ethnic tensions that dominate Nigerian politics.

Photo credit to PIUS UTOMI EKPEI/AFP/Getty Images.

Graphics credits to Stratfor, Der Spiegel and Electoral Geography.

5 thoughts on “Nigeria emerges as Africa’s largest economy”